Barely one month ago, Florida’s Republican governor Ron DeSantis was on a victory lap. The state’s average rate of new Covid-19 infections was the lowest in the nation, and a lapdog legislature was about to sign into law his sweeping new coronavirus measures, including the outlawing of mask and vaccine mandates in pursuit of “striking a blow for freedom”.

There was no mention of the 61,500 Floridians who have lost their lives to the virus.

Now, with the highly transmissible Omicron variant gaining a foothold in the US and likely already present in Florida, doctors say, the robustness of the governor’s controversial steps could be about to receive a first real test.

And while health experts and DeSantis’s political opponents agree it is too soon to know exactly how the state could be affected by any spread of the variant, they are worried. The rigidity of the DeSantis anti-mandate laws, including the removal of local authorities’ power to enact community protection measures based on conditions in their own areas, they say, could allow Omicron to circulate at a faster rate than it otherwise might.

Evan Jenne, co-leader of the Democratic minority in the Florida house of representatives, accused DeSantis of fitting Florida with “concrete shoes”.

“At the beginning of the pandemic a lot of free rein was given to local governments, because they were the ones with boots on the ground, they were the ones seeing what was happening and a lot of people were saved an untimely death because of actions of local governments,” he said.

“By hamstringing them, by putting their hands behind their back and lacing up concrete shoes, it’s just going to make it that much more difficult. When you have a government the size of Florida’s, covering 22 million people, it’s going to be less nimble and less agile than the smaller, local governments and our local health departments.

“Having an executive branch take all of that authority and power away from them is just not going to be a good move for public health into the future.”

Jenne and his Democratic colleagues were vocal opponents of the measures, but outnumbered by Republicans almost two to one during last month’s special legislative session convened by DeSantis, a Donald Trump protege who is tipped for a presidential run in 2024.

Since the summer, a period in which his state recorded its highest coronavirus death rates since the start of the pandemic, DeSantis has also battled with and fined school districts and local authorities over vaccine and mask mandates, offered $5,000 payments to unvaccinated police officers to work in Florida, and appointed the tendentious Dr Joseph Ladapo, a fellow skeptic of vaccine and mask mandates, as Florida’s new surgeon general.

“If Donald Trump says I’m not running to be president again, Ron DeSantis will be the Republican nominee for president without question, and a lot of the stuff that you’re seeing him doing is buoying that idea and reaching out to his base and a particular segment of society that loves this stuff,” Jenne said.

“Politically, I think it’s a wise move. For public health I think it’s dangerous.”

Other elected officials, healthcare professionals and parents have also accused the governor of putting politics ahead of science.

The notoriously prickly DeSantis, meanwhile, continues to present himself as a defender of the Florida economy, and citizens’ freedoms against the perceived tyranny of the Biden administration’s efforts to implement national mandates or lockdowns.

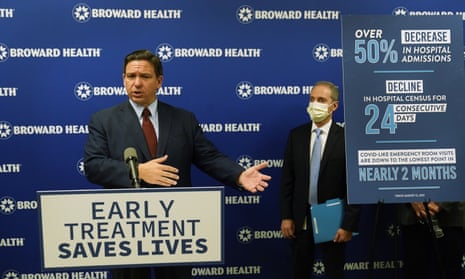

At a press conference this week defending the new laws, the governor was asked about the Omicron variant, and lashed out at a familiar target: what he sees as “corporate media” controlling the conversation around Covid-19.

“We are not, in Florida, going to allow any media-driven hysteria to do anything to infringe people’s individual freedoms when it comes to any type of Covid variants,” DeSantis said, before turning his attention to Biden and the chief White House medical adviser, Dr Anthony Fauci, a familiar sparring partner.

“In Florida, we will not let them lock you down,” he said. “We will not let them take your jobs, we will not let them harm your businesses, we will not let them close your schools.”

Jay Wolfson, distinguished professor of public health, medicine and pharmacy, and associate vice-president for health law at the University of South Florida, sees little prospect of DeSantis backing down if Omicron takes hold in the state.

“I don’t expect the governor nor the Florida legislature are going to change their position, unless, God forbid, the death rate increases,” he said. “People will get sick, the hospitals might get crowded, but unless people are dying, it’s unlikely that the policies are going to change.”

Wolfson noted that with DeSantis’s measures now enshrined in law, rather than executive orders that can more easily be challenged, there appears little appetite to defy him. All of the Florida school districts that once implemented strict mask mandates for students and staff have now terminated them, although many said it was because classroom coronavirus cases have fallen.

Meanwhile Disney, one of the state’s largest employers, dropped its requirement for cast members to be vaccinated.

“There’s no exemption for venues where there’s a higher risk of contact, such as theme parks, or a hospital, so you’re creating an environment where it’s increasingly likely that unvaccinated people will be exposed and get sick, and people whose vaccinations have declined efficacy could be exposed to those people and others and they could get sick,” Wolfson said.

“But we just don’t know yet to what degree the Omicron variant is both more contagious and more virulent. We’re rolling the dice.”