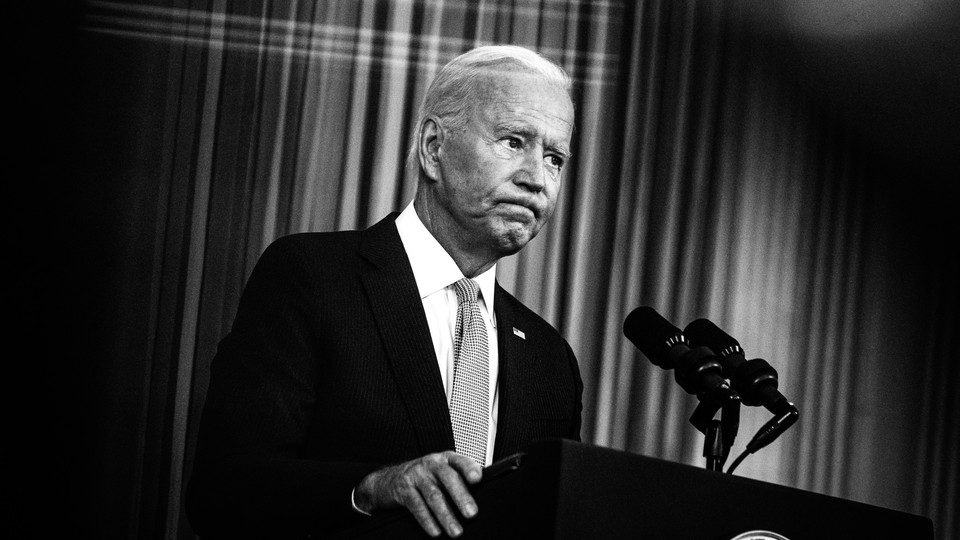

Joe Biden’s Year Was Ruined. Whose Fault Is That?

The president doesn’t control the economy, and a lot of presidential politics is just plain dumb luck.

Sign up for Derek’s newsletter here.

Imagine it’s November 2020, and I offer you the following vision of Joe Biden’s first year in office:

Stocks will soar. Consumer-spending growth will set land-speed records, and the president will oversee the best labor market of this young century. Coming off a flash-freeze recession, the U.S. unemployment rate will dip under 5 percent, lower than it was in every month of 2016. Blessedly, pay is rising fastest for low-wage workers. The number of job openings will set an all-time record, making this year possibly the best for finding a new gig since the end of the Second World War.

Sounds pretty good, huh? Then I offer another vision:

Americans hate foreign-policy mess on TV, but the U.S. will withdraw from Afghanistan with (no matter where you stand on the ethics) an indisputably messy finale. Americans are sick of plague, but over the summer, a new coronavirus variant will take over the country, killing tens of thousands of people and keeping masks pinned to faces. Americans don’t like overall inflation, and they really, really don’t like higher gas prices, but both will increase faster than at any point since the early 1990s.

Biden’s first year has been an unpredictable, best-of-times, worst-of-times mishmash. For now, the public seems to be holding the president responsible mostly for the worst bits: Biden’s approval rating at the end of his first year in office is lower than that of any American president since 1945, besides Donald Trump. More than 60 percent of voters say Biden is responsible for rising inflation, and now they’re souring on his handling of the Delta surge as well. On Fox News, commentators are regularly blaming the president for prices “spiraling out of control … like the ’70s.”

Both the public and the media sometimes see the president as the commander of our ship of state—a kind of all-powerful steward of all affairs economic, geopolitical, and biological. But they should take the nautical metaphor more literally. Navy captains seem in control, but they inherit ships built by other people and steer vessels through wind and waves that don’t obey any sort of direction. That—not omnipotence—is the reality of the American presidency.

“Presidents get way more credit than they deserve when things go well and way more blame than they deserve when things go badly,” Jason Furman, the chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama, told me.

Presidents aren’t powerless, and it’s unhelpful to pretend so. Biden’s decision to stick with Fed Chair Jerome Powell was wise and meaningful. Biden had extraordinary control over the Afghanistan pullout and could still do much more to accelerate the distribution of cheap rapid COVID-19 tests. Furman himself warned the White House in February that the Biden stimulus bill might contribute to inflationary pressures (and I believe that, at least in part, Furman was right).

But when it comes to the issues that are most likely driving the majority of public dissatisfaction right now—such as gasoline inflation, supply-chain snafus, and the rise of Delta and other coronavirus variants—the president’s circumscribed powers are best analogized to a small rudder turned by a captain amid an angry sea.

“It’s likely that things will be in better shape a year from now, but most of the economy’s problems can only be solved with time,” Furman said. “That’s a really hard thing to say as president.”

Biden inherited an economy he didn’t build, sundered by a pandemic he didn’t start. He oversaw the distribution of a vaccine he didn’t develop, and his inoculation campaign ran headfirst into vaccine resistance he couldn’t control. He was slammed with a viral mutation he didn’t ask for, then got punished by an international supply-chain mess, which slammed into domestic logistics problems overseen by private-sector transportation companies he can’t command, compounded by trucker shortages and port inefficiencies he couldn’t go back in time to fix.

And then there’s gas. Strong evidence shows that voters reserve special hatred for rising gasoline prices. But this is another phenomenon that is largely out of Biden’s control. The economy has snapped back to normal and so have gasoline prices, which—for all the panic inducement you’ll see on TV—are still lower than they were for much of the 2010s and only $0.50 per gallon more than they were in 2019. Biden is being blamed largely for rising prices in a quickly expanding economy—a predictable outcome of catch-up growth (over which, again, he has at best limited control).

So what should Biden do, recognizing the limits of his own power? Cheer and vow.

The president should speak up about what’s been accomplished—“This is the best labor market of the century!”—and cheer on private-sector companies, such as those in domestic transportation logistics, whose increased efficiency is necessary to resolving America’s painful shortages. He should also tell people that he feels their pain on COVID-19 and inflation and announce a small number of easily achievable goals, like the production of several hundred million rapid COVID-19 tests made free for—and even personally mailed to—every American.

If that doesn’t work, there is always the serenity prayer. The White House can’t control the variants, or supply chains, or global energy markets. If COVID-19 and the global supply chain of November 2022 resemble those of November 2021, Democrats are going to get clobbered, no matter what. Some of Biden’s problems, however, may resolve themselves: Oil and natural-gas prices have come down in the past week, analysts at Morgan Stanley have predicted that supply-chain bottlenecks will be normalized within the next year, freight rates for goods shipped from Asia to the U.S. are dropping, and, blessedly, chicken inflation is slowing too.

“If rising food and gas prices and global supply chains don’t get better, Biden will be in trouble, and if they do get better, it may have almost nothing to do with what he’s done, and he’ll get credit anyway,” Furman said. After a pause, he added: “Well, that, or people will find another reason to complain about him.”