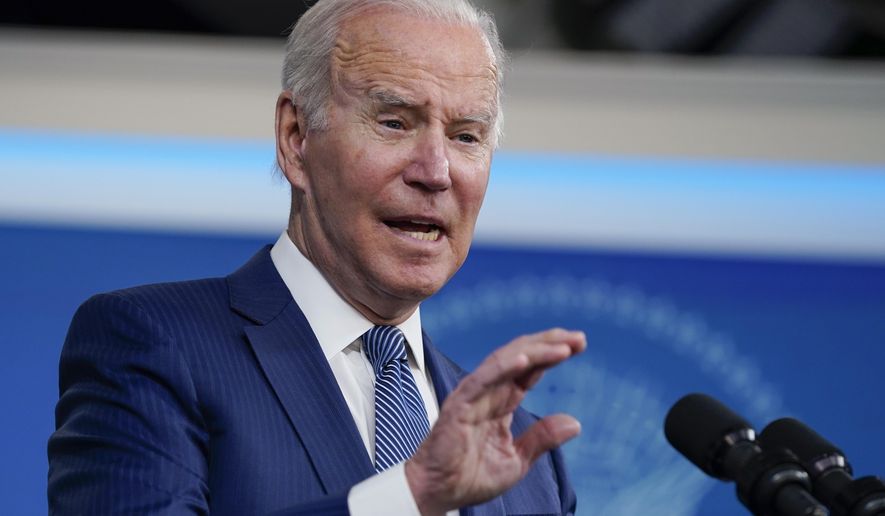

The goal behind President Biden’s upcoming “Summit for Democracy” was to feature U.S. leadership and unify like-minded democracies, including many the administration hopes will work together to counter communist China’s rise as a rival, autocratic global power.

But the summit, a key promise of Mr. Biden’s 2020 presidential campaign, might backfire before the virtual Dec 9-10 event kicks off. Critics and news outlets around the world are questioning the White House’s picky invitations, and U.S. adversaries are scrambling for favor among nations left off the list.

Singapore is among the major democracies conspicuously left off the list of 110 participating countries, while the inclusions of Pakistan and others have triggered speculation about the strategic calculus behind the invitations.

Turkey, a critical NATO ally, didn’t make the cut. Iraq did, despite having a parliament heavily influenced by the nearby theocracy in Iran.

Turkey instead got lumped with China, Russia and other nations left off the list. Moscow and Beijing are now seizing the moment to attack the very idea of the summit and delighting in the tensions it has generated.

The Russian Foreign Ministry said it is hypocritical of the U.S. to claim to be “a ‘beacon’ of democracy, since they themselves have chronic problems with freedom of speech, election administration, corruption and human rights.”

Chinese officials accused the White House of using the summit to ratchet up Cold War-style tensions with Beijing. “This year marks the 30th anniversary of the end of the Cold War,” Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Wang Wenbin told reporters this week. “The U.S. hosting of the summit for democracy is a dangerous move to rekindle the Cold War mentality, to which the international community should be on high alert.”

‘Strange’ choices

Even some on the invitation list have raised questions. A high-level source from one participating Indo-Pacific nation said it appears “strange” for Pakistan to have an invitation while Bangladesh and Sri Lanka do not. Sri Lanka is widely regarded as the oldest democracy in Asia.

The source, who spoke on the condition of anonymity, questioned whether the administration used the invitation to smooth over ill feelings in Islamabad stemming from Mr. Biden’s failure after more than 11 months in office to phone Pakistani Prime Minister Imran Khan. The administration, the source said, may be trying to appease the Khan government in exchange for assurances that U.S. forces can rely on Pakistan to be a partner for regional counterterrorism operations, including in Afghanistan.

Such assurances would be welcome when the White House seems to be struggling to reach basing agreements in the wake of the messy troop pullout from Afghanistan. Tajikistan, left off the summit invite list, is a key Central Asian prospect.

Patrick Cronin, the Asia-Pacific Security chair with the Hudson Institute in Washington, cautioned against “rushing to judgment” about why some countries were invited while others weren’t. Still, he said “there are practical reasons some friends of the United States were probably not invited.”

He pointed to Singapore as an example. The Southeast Asian economic hub is known for its vibrant parliamentary democracy and for being caught in the middle of U.S.-Chinese geopolitical jockeying.

“Singapore is being spared the awkwardness of appearing to side with the U.S. and against China,” Mr. Cronin told The Washington Times. “Singapore likes to focus on being a trading hub, rules and good governance, but it also likes to avoid unnecessarily ruffling feathers. That is why it is a partner of the United States and not an ally.”

Still, Mr. Cronin emphasized that the “simple act of inviting countries to participate in a summit for democracy sends a signal that Washington expects participants to live up to democratic norms and non-invitees should step away from authoritarian governance.”

Such logic could explain why Turkey didn’t make the cut, given widespread perceptions in Washington of the increasingly authoritarian nature of Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan.

Fighting the autocrats

Biden administration officials have emphasized that a central aim of the summit is to gather government, civil society and private-sector leaders to work together to fight authoritarianism and global corruption and to defend human rights.

A message from Mr. Biden touting the summit on the State Department’s website says the administration is consulting with experts from government, multilateral organizations, philanthropies, civil society and the private sector to solicit “bold, practicable ideas “around three key themes: defending against authoritarianism, addressing and fighting corruption, and promoting respect for human rights.

“Since day one, the Biden-Harris administration has made clear that renewing democracy in the United States and around the world is essential to meeting the unprecedented challenges of our time,” the message states.

Some perceive the reference to “renewing” democracy in the United States as an attempt to stoke Democratic partisan fervor around the notion that President Trump represented a significant decline in U.S. democracy. Many on the left say that was underscored by the Jan. 6 storming of the U.S. Capitol by pro-Trump demonstrators.

With that as a backdrop, some observers question the extent to which internal or foreign autocratic forces are challenging democracies.

Financial Times opinion writer Janan Ganesh said in a column this week that the summit “risks flattering the unfree world.”

“Its premise, that a contest is going on between democracy and its opposite, is right. But the fault line runs mostly through countries, not between them,” Mr. Ganesh wrote. “By calling nations together, and barring Russia, Turkey and China, the event reframes a largely domestic problem as a geopolitical one. It encourages the idea that foreign subversion (which is real enough) is to blame for Donald Trump in the U.S., the dark vaudeville of Brexit, the numerous flavors of Italian populism and the great mass of anti-liberal votes in France.”

Geopolitical focus

Others have focused on the geopolitics of the summit itself.

The Australian newspaper cited critics questioning whether U.S. strategic interests may have been as vital to the invite list as any given country’s democratic bona fides.

“Important U.S. allies Pakistan and the Philippines made the list despite endemic corruption and human rights abuses,” an analysis by the paper stated this week. “Yet Singapore and Thailand — respectively one of America’s closest regional security partners and one of its oldest regional allies, notwithstanding their deeply-flawed democracies — have been excluded alongside one-party-state Cambodia, communist Vietnam and Laos, the kingdom of Brunei and the murderous Myanmar junta.”

Ben Bland, Southeast Asia program director at the Sydney-based Lowy Institute, told the paper that the “Biden administration seems to have picked some states because of their genuine commitment to democracy while others appear to be there more because of their strategic relevance.”

The invitation list has exposed inherent tensions in U.S. efforts to build a broad-balancing coalition against China while framing competition with Beijing in ideological terms, Mr. Bland said. “The fact that only three ASEAN members are invited,” he said, “shows that pitching competition with China as a grand battle between democracy and authoritarianism will not get Washington very far in Southeast Asia.”

Mr. Cronin said the administration is approaching the summit “not from a position of supreme confidence born of some unipolar moment, but from a position of necessity to push back on illiberal governance at a moment of profound crisis in democracy.”

“In our age of plurilateralism, in which various constellations of countries can choose to partner or opt out of specific frameworks, it would be great for most participants to sign onto an agreed set of democratic principles regarding rules of the road, including for digital technology,” he told The Times. “Over time, a summit process might enhance not just the confidence but also what some have called the operating system of world order.”

Correction: Sydney was misspelled in an earlier version of the story.

• Guy Taylor can be reached at gtaylor@washingtontimes.com.

Please read our comment policy before commenting.