Over the past decade, I’ve been blown away by Greig Fraser’s diverse work behind the camera. As the cinematographer on projects like Zero Dark Thirty, Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, Vice, Lion, Foxcatcher, Killing Them Softly, Lion, the first season of The Mandalorian, and others, he’s shown again and again why he’s one of the best directors of photography working in Hollywood. And his resume and incredible work explains why Denis Villeneuve called on him to helm his dream project: Dune.

As I have said many times, Dune is my favorite film of 2021, and everyone involved in the making of this masterpiece should be thanked for making audiences feel like we got to leave our planet and see the other side of our galaxy come to life. I haven’t felt this transported watching a movie in a very long time and Fraser’s brilliant work is one of the reasons the film is such a masterpiece.

With Dune returning to select IMAX screens for a week starting tomorrow, I recently got to speak with Fraser about making the film. During the wide-ranging conversation, Fraser talked about how Villeneuve asked him to be involved, what’s the first thing that happens after he starts on a new job, the way each director he works with likes to shoot on set, the shot he is especially proud of, and more.

However, while the entire conversation was great, one part stood out and it was when we talked about why the daylight VFX in Dune looked so amazing. Like all of you reading this, I have seen plenty of movies with extremely bad VFX during the day. And I’ve always wondered why. Fraser explains that it’s a result of bad lighting when the scene is being shot and how even the best VFX people on the planet can’t solve bad lighting.

He tells a great story about what it’s like on set and how it can sometimes work:

“So what happens is you as a DP, sometimes you go into a studio, they say, "Hey, light a desert island. Here's some sand, here's a palm tree, light it and make it look good." And you're like, "Well, hang on. I'm on a stage in London, in Pinewood, it's raining outside. What do you think I should light this with? Tungsten light?" Tungsten light's warm. And so basically, you are given the worst environment to create something that's realistic. That's how a normal film works.”

He continues.

“In Dune, we had Paul (Lambert), who was our VFX supervisor, and he was all about the light. He knew that if I shot something incorrectly, that it would look wrong. There's nothing that he could do. The best VFX people on the planet could not solve bad lighting. And it's not that DPs do bad lighting, it's that they're given bad situations to do lighting with. And they can't fix it. They're trying to light a street scene outside in the middle of the day, and they're on stage. Yet they've got tungsten lights and an HMI. It's not enough lighting to do the right thing.

So there were certain scenes that we had, like the ornithopter scene that's flying ... the worm eating the spice harvester. When we're in the ornithopter, flying over the desert, you sit around in a production meeting, and you say, "Okay, scene 52, ornithopter interior. How do we shoot that?" Everybody goes around and says how they would like to shoot it. And invariably, everybody wants to shoot it on stage. Because inside, it's controllable, and you can light it, and there's no issue with running out of daylight. There's no issue with rain. There's nothing. It's just completely controllable. But Paul and I both knew that would never look good. So then we went, "We have to be a outside for it. We have to use real daylight and real sun." So therefore they pushed it to the back lot. And the back lot wasn't right. So the back lot wasn't right, because the back lot, we have to surround with blue, to block out the buildings on one side, the road on the other side, the telephone poles on this side.

Suddenly you've got blue screen all around you, which means the light is affected. So what we pitched was the idea that we find a hill in Budapest. So we found the highest point in Budapest. We put the gimbal on the highest point, and we built a dog collar type thing around the base of the gimbal, with the ornithopter on it. And that dog collar was the color of sand. So when you looked outside and blurred your eyes, there was sand color from here down, and sky from here up. That was it.

We were just replicating the real world, and it looked amazing. It looked so real and all Paul had to do...He just had to do very little VFX on that, to make it feel right. It all stems from the beginning, that the reality of how you shoot it. And how you shoot it to be real and correct? If you are trying to blow your eyes and say, "It'll be right later on, we'll fix it later on," it won't be, it can't be.”

This attention to detail is one of the many reasons why Dune is such a special film.

Here’s the full conversation. Finally, if you have yet to see Dune and you feel safe going to a movie theater, I strongly suggest watching it in IMAX while you have the chance. This is not the kind of film that you should watch on the small screen for the first time.

COLLIDER: You have shot a number of cool things. I'm curious if someone had never seen your work, what do you want them to watch first and why?

GREIG FRASER: Wow, that's a great question, because it feels to me like the work that I've been fortunate enough to have done, has kind of ticked every box of my movie-going pleasures, when I was a teenager, when I was a kid, when I was a young adult. So it feels like I've managed to do a Star Wars, which means big tick. I've managed to stand in a portable bathroom with a stormtrooper. I mean, who else can say they've done that? I've stood in a urinal, standing next to a stormtrooper. It's pretty fun.

But also, at the same time, my other young adult senses have been kind of worked on with films like Bright Star, with John Keats, the poet. So I've been able to kind of work on my more cerebral upbringing. And films like Foxcatcher, and also films like Zero Dark Thirty. I love that story of the raid on the Bin Laden compound. I remember when that happened, I read everything I could in the media, what was going on in that, because I was super interested in how they planned that. Then when that film came to me, I was like, "I have to do this."

So if you want to know me as a personality, you probably need to watch every single film that I've done. Because for the most part, maybe barring two films or three films, which I won't ever name, you're watching my film loves, by watching the films that I've done.

Whenever Zero Dark Thirty comes on, if I'm flipping the channels, it just pulls me in every time. I can't turn away. I'm curious how has technology impacted the movie-making process over the last few years? Obviously, you worked on Mandalorian, you used The Volume technology, but I would imagine each year there's technical advances... I'm just guessing. I'm not a DP, but has that been the case? Has that helped you as a cinematographer?

FRASER: It's a double-edged sword, because yes, you could say it has. But whenever you are breaking new ground or whenever you are moving the needle, when it comes to an established norm, there's plenty of opportunity for that norm to be infiltrated by others sources that aren't necessarily qualified or able to be in that space. That sounds very roundabout way of saying it's a bit of a land grab.

Whenever there's a new technology or a new way of doing something, there's often a bit of a land grab between departments about how they work that technology. Like the virtual space, The Volume, it's a bit of a land grab between post-production and production. As a DP, I'm in production.

Post-production creates the content for that space. So therefore they tend to try and take ownership of that. And it's not through any nefarious reason. They just feel like they're the best qualified to do that. And they probably are. But then that's also then infiltrating me in the production space. So it's a balancing of the skillset of ... So post- production and of production. It's the same with CG when it comes to maybe makeup, or it's CG when it comes to kind of other aspects. Whenever there's a new technology push, there's always a bit of a land grab when it comes to who controls it or who is the best qualified to be in charge of that particular technology.

So it's been quite clear. When we went from film to digital with the Alexa, let's say, or the RED One or Sony, it was quite clear who controls that. That was the DP. But then suddenly you have DITs, right? And the DIT was a new position. And yes, they worked for the director of photography, but that could have easily have worked for post-production or the editor. So it's trying to make sure that that land grab of new technology, it's beneficial to the end product.

What is your favorite camera to use and favorite lenses to use and why?

FRASER: I can't answer that, nor will I answer that, because I got told the other day by somebody that I was a certain guy, as in ... I mean, I won't name the brand, but I was a XYZ guy. I was mortified that somebody thought that I was an XYZ guy, mortified. I felt that I am the most agnostic human being to walk the planet. I will tell you what I like, and I'll tell you what I've used, but I would like to believe that my brain isn't so closed in, that I can't-

No, I get it. You pick the lenses and the camera based on the project at hand.

FRASER: Yep, exactly. So to answer that question as more of a riddle, I'd say, well, what have I used for the last six films digitally? What lenses have I used for the last six films? I mean, again, it sounds a little bit kind of ridiculous, I like to believe that I'm open to new technology, to the point where, if something comes out, that I will give it a very good consideration. And in fact, I'm looking at doing a film soon. It's not official or anything, but I'm looking at using a camera, which is not a camera I've used before.

I won't press you on that beyond you telling me down the road.

FRASER: Yes, exactly.

So jumping into Dune. I'm curious, how did you actually get involved in this thing? What is it like? Is it Denis, sending you an email or a phone call and saying, "Hey, do you want to have a meeting? Can we talk?"? How does that actually work?

FRASER: I don't know. It's weird, because I've known Denis now for a number of years. So I met Denis at a barbecue at Roger Deakins' house. So I think after they finished Sicario, Roger had a barbecue. Roger and James are very, very sociable people, pre-COVID of course. And they like to have lots of people around and have a good chat.

I met Owen Roizman at Roger and James' house. And I learned that Owen Roizman has the rug in his house, the piss rug that was peed on during The Exorcist. I was like, "Oh, my God, you have that rug." Because my wife is in the rug business and designs and makes rugs. So it was a point of discussion that he has the pee rug, or the piss rug.

Anyway. So I met Denis at one of Roger's barbecues. I'd seen Polytechnique and Incendies before that, but I didn't realize I was talking to the director of that film or the director of the film that he just finished. I met this guy that was really warm and endearing and interested and interesting. I was like, "Wow, he's a nice guy."

I said, "Roger, where’s Denis?" Because I saw his name, but I didn't know it. And, "Oh, that's Denis. He's the director of Sicario, and he directed," blah, blah, blah. And I went, "Oh, it's Denis Villeneuve. Oh, shit. Wow. Oh, my God. Wow."

And that was when Denis was a good young director, like a good junior director of small Canadian films and a couple of good American movies. So I'd always watched his work, and I thought he was just such a lovely man. You know? When he called me...I also worked with Patrice Vermette, who is his designer on Arrival, Sicario, Prisoners, Enemy and on Vice. And I love Patrice. He's a French-Canadian man with a passion. We got along really well.

Again, I don't know the situation in regards to Denis' other cinematographers, because he has great relationships with cinematographers, but he called me and said, "I'd love to talk to you about doing this film I'm dreaming of, and it's called Dune." And I said, "I would love to talk to you about that. Thank you very much."

So you get hired. What exactly goes on behind the scenes when Denis says, "Okay, you're hired." Take me through what exactly you're doing prior to stepping on set that first day.

FRASER: Oh, hell. I mean, dude, how long do you have?

Maybe that's too big of a question.

FRASER: Maybe. But I tell you, I can tell you that, that we talk about a lot of things. I sit there, and I listen to him talk for three hours. That's my first of job is to listen to him empty his brain. He's been obviously planning this movie since he was 14. He's been formulating a brief to a DP since he was 14. So I have to sit there and listen to him empty that well of idea that he has had since that time. It's absolutely fascinating, because Dune wasn't a book that I was passionate about as a kid, it wasn't something that I read. I was a Star Wars kid, generation-wise.

So Dune was something that the big kids read, the older kids read. I never got around to reading it in its true form, but Denis had. And he was super passionate about it. My take was that I listened to him for the three hours or whatever. I absorbed it, and I understood what he was saying. Then I went away and came back with some thoughts technically, about how we shoot, where we shoot, what we shoot on, what's the format, what we test, what we look at, how we test. There was a thousand ideas that I had and maybe a hundred of those ideas made the final movie.

How does it work on set in terms of the way you collaborate with Denis? Was a lot of stuff storyboarded? Or even if you have storyboards, are you then tweaking it in the moment based on what you're given?

FRASER: Well, Denis does love to storyboard. He loves to dream about the film. I was doing Mandalorian when he was storyboarding, so I didn't do as much storyboarding with him as I would've liked to. I think he may have storyboard with Roger more than I had with Dune. I would've loved to have done more. But at the same time, he was free, just to kind of dream and think and ideas.

I was at the NFTS, the National Film and Television School in London. And somebody asked me, because Denis had been there the day before. So Denis had said, "When Greig came on, a lot of the film was storyboarded." The question came like, "Oh, how did you feel about that, coming onto an storyboarded film?"

My response was, "Well, listen, you've got Denis Villeneuve storyboarding a movie. One." It's great storyboards. I would have to be a jackass to feel anything except extreme excitement and gratitude that I was being given storyboards that were already well-conceived and well-thought out to visualize. You know?

And it wasn't everything of course. It was key elements, key scenes. And Denis and I also had boarded together as well, but he had done a lot of boarding before that. But they were really good. So, I'm looking through his storyboards, going ... Again. I'd be a jackass if I turned around and went, "Yeah. I'm not sure about those. They're not right, " because they were good. And you've seen the movie. I mean, dude, they were freaking good.

The movie is, let me use the right term here, a masterpiece. I don't know why you would ... If someone's handing you gold, you don't turn it down.

FRASER: You'd have to be an idiot. That's the thing. So my response to that with the storyboarding thing was ... They were great storyboards. Now, going back a little bit to the question you asked. Yes. On the day, if something changes, if the set looks different to the board, so therefore the frame is slightly different, of course.

I have to be honest with my opinion. And I always am. And Denis is always honest with his opinion, which is why I love working with the man. There's no contemplation of each other's ego. We don't go, "I'm worried about what he's going to think if I say I don't like that." It doesn't happen with him or me, I hope, with him anyway. It's like, "What about if we do that? What if we do this instead?"

It was complete free-for-all. Often, we came back to the boards, but there were times we didn't were, times we diverged. That's where the joy comes from is like going, "You've got a great shot here. Let's shoot it." Because it's been concepted and storyboarded and then the actors have done something different. So let's respond to the actors and make something that's better than what we could have planned.

With the movies you've worked on and specifically with Dune, what's the most cameras you've used to capture a scene? And what do you typically use on most takes?

FRASER: Well, "typically" is a loaded question. Because again, going back to that thing about what type of camera do I use? I prefer to be agnostic when it comes to that question.

How many cameras do you prefer to use? Well, it depends on the director. Like Jane Campion, one camera. Garth Davis, one camera, often two cameras. Denis Villeneuve, mostly one camera. Bennett Miller, mostly one camera. Like Kathryn Bigelow, 17,000 cameras, if we could fit 17,000 cameras in the room, but that's not...she loves coverage, and she love to kind of feel it.

I spoke to people that worked on The Last Duel with Ridley, and I guess every scene, he had four and five cameras, every scene.

FRASER: I find that to be... That's hard. That's really hard, because A camera looks fantastic. Then B camera ... It's diminishing returns. But what it creates is something that's...the fourth camera gives you something that's different to what the A camera gives you. You know? And it's challenge in itself.

And I loved doing Zero Dark Thirty, going back to that film, because it had four cameras. I had to light a two-hander at a desk, in a room with four cameras. I couldn't figure out where to put those cameras, because they were going to be in the shot. So that's a challenge in itself, which I love.

You filmed all over the world with this movie. I'm just curious, was there a day that the cameras basically said, "Fuck you."?

FRASER: No, because they were really good cameras and built by very good camera companies. No, the cameras were...I'll tell you what. There was one day ... Well, no, it wasn't the camera to blame. There was one day that a storm came in, in Budapest. All the cameras were in tents. My A camera AC went, "Bag all the cameras. Cover them. We'll go inside. We'll get out of the rain." It was thunderstorms and lightning. It was dangerous to be outside. So they had to make safe on the cameras.

And one of the cameras, the guys didn't bag, they just put under the tent. And the rain came in sideways. So basically, drenched the camera. So we had a little bit of issues with the camera then. But I mean, come on. It was water inside a camera, which I don't blame the camera company or ... That was just us not being smart enough about bagging the cameras.

Yeah, that's not definitely a camera fault.

FRASER: No, no, no, no.

Which is a shot that you are especially proud of on Dune?

FRASER: I love shooting in the desert. There's something magical about Jordan and Abu Dhabi. So you show me any of those shots, and I'll be pretty mad happy about most of those shots. I love the shots when we're following Stilgar. There's a shot where ... In the script, it's different to the way it's in the film, right? So again, this is the joy of editing, in that the story changes a bit when it comes to the edit.

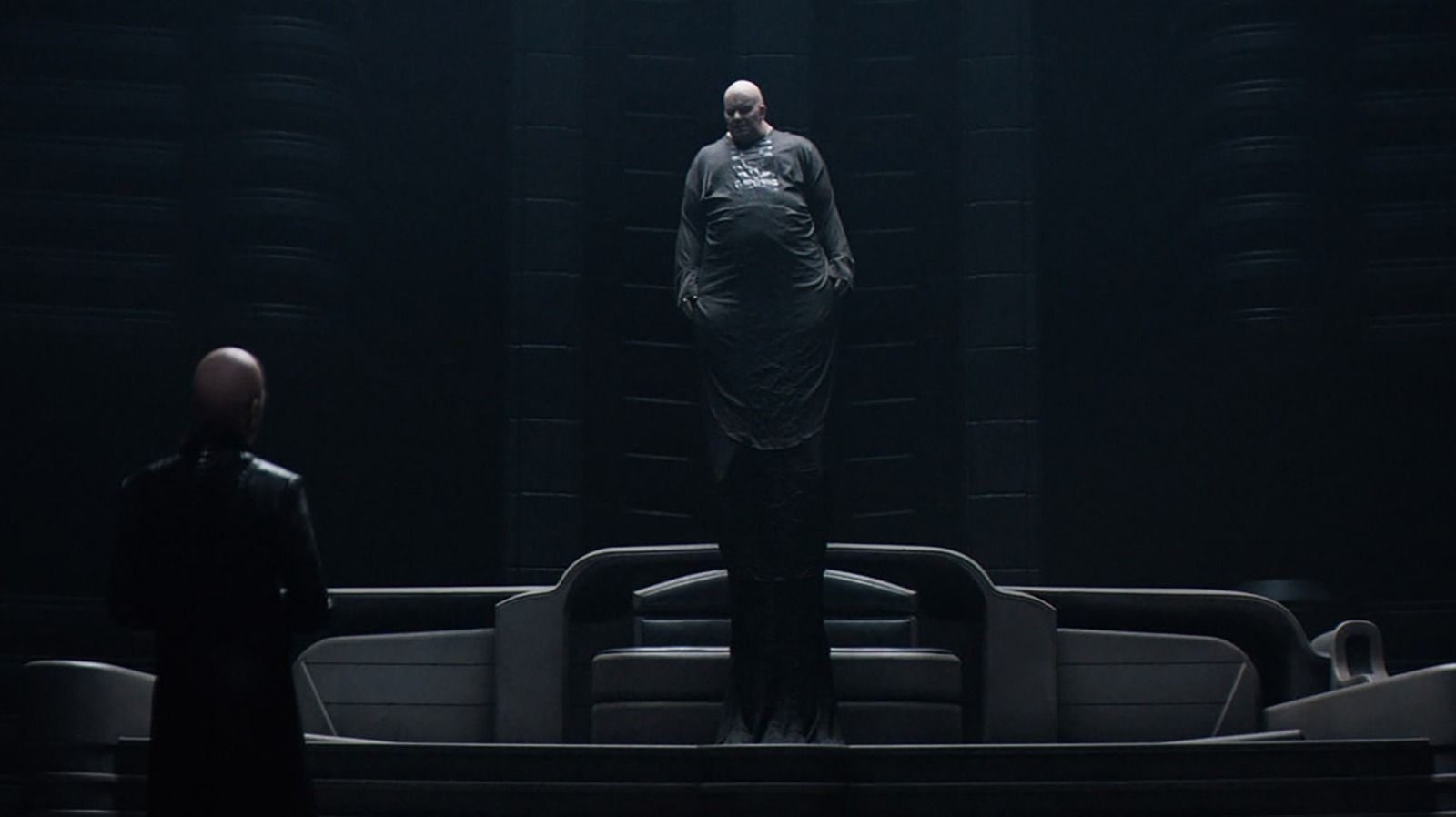

I think in the script, and I don't know if you have access to the script, but we're following Stilgar, as Stilgar senses the ship coming in, as the Atreides arrival into Caladan, that didn't make the edit like that. But the shot did make the edit. And it made the edit in the prologue. It's a shot basically starting on the walking with rhythm, without rhythm footsteps, as we're pushing towards the feet, as they're making the symbol. And we tilt up, and we've got the small figure of Stilgar in the background. There's just a wind gale, blowing across the scene. And there's a bit of spice in the air. Now, a bit of spice was added by post, but it just makes all the difference to the shot. The shot was beautiful before, but then Paul and his merry team of VFX people add a little bit of that spice in the sand, and it was just amazing.

There's a lot of daylight VFX shots in this movie, and they're really, really good. Can you sort of talk about crafting or working on these shots? Because daylight, VFX are really hard to make it look awesome.

FRASER: Mm-hmm (affirmative). Well, because we had the world's most amazing VFX supervisor, and because we had the world's most amazing director, and because I was able to contribute some plates to that, it was kind of ... Maybe I contributed 5% of what they got. No, but the approach from day one was right.

Normally, okay, so what happens is you as a DP, sometimes you go into a studio, they say, "Hey, light a desert island. Here's some sand, here's a palm tree, light it and make it look good." And you're like, "Well, hang on. I'm on a stage in London, in Pinewood, it's raining outside. What do you think I should light this with? Tungsten light?" Tungsten light's warm. And so basically, you are given the worst environment to create something that's realistic. That's how a normal film works.

In this world, we had Paul, who was our VFX supervisor, and he was all about the light. He knew that if I shot something incorrectly, that it would look wrong. There's nothing that he could do. The best VFX people on the planet could not solve bad lighting. And it's not that DPs do bad lighting, it's that they're given bad situations to do lighting with. And they can't fix it. They're trying to light a street scene outside in the middle of the day, and they're on stage. Yet they've got tungsten lights and an HMI. It's not enough lighting to do the right thing.

So there were certain scenes that we had, like the ornithopter scene that's flying ... the worm eating the spice harvester. When we're in the ornithopter, flying over the desert, you sit around in a production meeting, and you say, "Okay, scene 52, ornithopter interior. How do we shoot that?" Everybody goes around and says how they would like to shoot it. And invariably, everybody wants to shoot it on stage. Because inside, it's controllable, and you can light it, and there's no issue with running out of daylight. There's no issue with rain. There's nothing. It's just completely controllable. But Paul and I both knew that would never look good. So then we went, "We have to be a outside for it. We have to use real daylight and real sun." So therefore they pushed it to the back lot. And the back lot wasn't right. So the back lot wasn't right, because the back lot, we have to surround with blue, to block out the buildings on one side, the road on the other side, the telephone poles on this side.

So then suddenly you've got blue screen all around you, which means the light is affected. So what we pitched was the idea that we find a hill in Budapest. So we found the highest point in Budapest. We put the gimbal on the highest point, and we built a dog collar type thing around the base of the gimbal, with the ornithopter on it. And that dog collar was the color of sand. So when you looked outside and blurred your eyes, there was sand color from here down, and sky from here up. That was it.

We were just replicating the real world, and it looked amazing. It looked so real and all Paul had to do... And you should talk to Paul, because I can't speak for him. He just had to do very little VFX on that, to make it feel right. So it all stems from the beginning, that the reality of how you shoot it. And o you shoot it to be real and correct? If you are trying to blow your eyes and say, "It'll be right later on, we'll fix it later on," it won't be, it can't be.

Yeah it's so interesting you say that, because I think you've just answered why a number of movies I've watched have some sketchy things during the day. I think you've nailed it.

FRASER: If you ever want to sit with me and ask me why something looks sketchy, I will give you my best guess, knowing what I know. Because invariably, it's not because the DP is useless, not because the VFX people are useless. It's because it's a square peg in a round hole, that they're trying to force it in.

Well, the other thing, and I've spoken to so many people, where they're on set, they run into a problem, and the answer ... And mind you, I'm not on sets that much. But the answer is, the joke is, "We'll fix it in post." And when you fix it in post, it means you're kicking the problem down the road, and you are not giving the people in post the assets to make it look right.

FRASER: 100% correct. Yes.

I loved The Batman trailer which you shot. I specifically love the shot where Batman is in the hallway and the gunfire is the light that is illuminating the scene. Can you sort of talk about crafting that shot?

FRASER: It's a hard one to talk about, because yes, I've seen it, and you've seen it. The problem is, is that I can't talk about Batman. It's weird. It's a weird paradox, because you've seen it, and I've seen it. We all know. We've all seen me without my pants on, but I can't talk about the fact that we've seen will myself without my pants on.

Is it because the studio or people are telling you, "Don't talk about it," or you just don't want to talk about it yet?

FRASER: No, no, no. It's because ultimately, we're not in that period of time. I have spoken about things in the past that I probably shouldn't have, and it's just through pure guilelessness. I'm an innocent little wallflower that likes to talk about everything that I do. And I just need to self-control, because I could talk ...I can talk about everything, and I can't control myself, because ... But here's what I can say, I guess, without making it a big thing.

That shot in Batman...There's a number of shots in Batman that I want to talk to you about at some point in the future. When we're on that train, I definitely want to talk to you about that. Because for me, let’s talk about me personally, as a selfish thing. The last three years of my professional career, I've done two or three things that I have just been super ecstatic about. Like being able to have done a Batman is amazing. Having done a Star Wars is amazing. Having done Dune, which was the precursor for other shows in sci-fi, was amazing, with Denis Villeneuve, with that cast. So it's been a bit of a dream run in terms of a creative aesthetic kind of world that I've been in.

What was amazing about doing Batman after Dune was that there's not a single grain of sand in Batman at all, not a single grain of sand. The thing is, I emailed Denis. I did a commercial in Barcelona, and I packed my boots that I hadn't put on for a while. The customs and immigration people asked to see my bag. And I opened up the bag and all this Jordanian sand, just went everywhere in Barcelona. It just covered the floor. The guy just went, "Yeah, no, no, just pack it up, pack it up, pack up." I was like, "Oh, wow. I still have Jordanian sand in my luggage from that film."

You've worked with a lot of very talented directors. Is it pretty much when you're working with them, like really similar behind-the-scenes in the terms of the way you prep for a movie, the way it is on set? Or do you find that the different directors have a completely different way of collaborating and working with you?

FRASER: 100%, you've got to be completely malleable to their style, because some directors lean on you a lot more than others for different things. Some directors will lean on you to lens up the movie. They don't understand lenses, let's say, some directors. Some directors know the difference between a 17 and 75. And they know the emotional response that the 17 mil will give them versus the 75. So they'll be super precise about what lens you use.

I think part of the skill of cinematography is reading the room and understanding what the director needs and filling the gap. Because you have directors, like, let's say use David Fincher as an example. I've never worked with David Fincher, but he is an amazing lighting director. I know a number of his DPs, and I also know that he is very prescriptive when it comes to angles and lighting. If David Fincher became a DP, he'd be super successful. Maybe he should think about changing careers. Because I think if he'd became a DP, he would be a lot of directors' first picks as a DP.

Yeah. But the problem is he's the smartest person in the room. And I don't think he would work well with another director.

FRASER: Maybe, maybe.

Anytime I've been lucky enough to talk to him or James Cameron, or there’s been a few people I've spoken to, and I'm like, "Oh, you could do every job on this. You're on that level."

FRASER: Yeah. I mean, he is incredible. I had lunch with Darius Khondji a few weeks ago, and Darius just loves Fincher, like loves. And Erik Messerschmidt, I'm friends with, and he's a smart guy. So if you are working as a DP with him, that would be a very different set of parameters than say working with ... I don't know. I won't name director's names, but a director who doesn't give two craps about the lens and the film stock and the format. They just want to know that the actors are there, they're in their prime and they're giving the best performance.

As a DP, you deal with it, you light it, you visualize the whole film. So there's two gamut’s of directors. It goes from here to there. So yeah, you've got to be super mindful of the director you're working with, to fill the gaps that they need filled.