With No Rescue Equipment and a Dying, Paralyzed Partner, This Climber Dug Deep

Where do you find superhuman strength? If someone you love is utterly dependent on your efforts, sometimes you discover it’s already within you.

Note: This is part six of a 10-part story, which will be released weekly. Visit Ordinary Heroes to find the other parts as they are released.

Climber: Celia Bull

Location: The Totem Pole, Tasmania

Date: February 13, 1998

The Scene

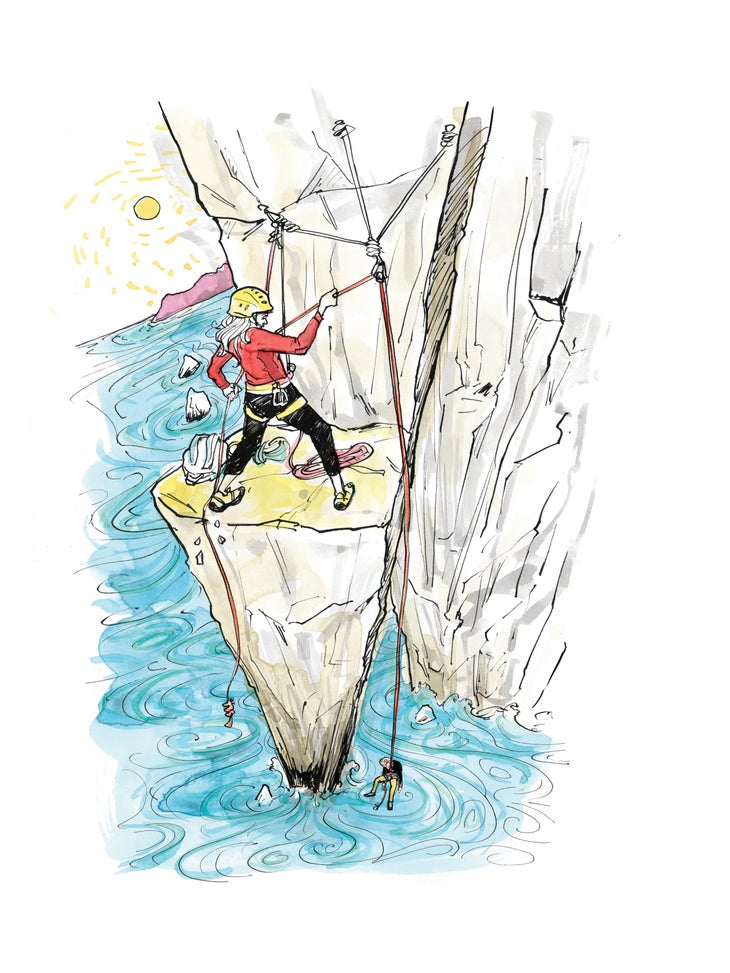

In 1997, British climber Paul Pritchard had just won the Boardman Tasker Prize for his book Deep Play, and he and then-girlfriend Celia Bull were spending the award money on a round-the-world climbing trip. In Australia, Pritchard’s big goal was a free climb of the Totem Pole, a slender spire on the southeastern coast of the island of Tasmania. The spindle, just 12 feet thick and rising over 200 feet high from the Tasman Sea, had been freed just two years earlier at 5.12b.

Both Pritchard and Bull were highly experienced climbers, known for bold traditional ascents. Individually or together, they had climbed in Pakistan, on Baffin Island, and in Patagonia. On Friday the 13th, they approached the Totem Pole by hiking nearly five miles to the isolated headland. Filmmakers had recently installed a Tyrolean traverse leading from the mainland to the summit of the spire, but there was no one else around that day. Pritchard and Bull decided to cross the Tyrolean and rappel the spire’s face instead of doing the traditional rappels. Pritchard, then 30, went first, rappelling the full length of a 60-meter rope.

At the foot of the formation, a wave soaked him and the bottom of the route, making it impossible to climb. He called up to Bull to rappel to a midway ledge; he would jumar back up so they could attempt the top half of the spire. Pritchard tucked his legs under him to avoid the waves and swung onto the rope to begin ascending. High overhead, the taut rope snagged a loose block the size a small television and pulled it free. The rock plunged 90 feet toward Pritchard, striking him directly in the head.

The Response

Bull heard the crash and looked down to see Pritchard hanging in a prone position. She anchored her rope at the midway stance and rappelled to him. He had a 4” by 2” hole in his skull, with blood and who knows what else pouring into the sea, and was lapsing in and out of consciousness. He didn’t know it yet, but he was paralyzed on his right side. He could not assist with his own rescue.

“You’ve taken a little rock on your head, but you’ve had worse,” Bull reassured him.

Pritchard was hanging below the high-tide line. Bull felt the only place she’d be able to safely leave him and go for help would be the midway ledge, about 12 feet long and 3 feet wide. But first she’d have to haul him to that point, 100 feet higher.

Bull raised Pritchard upright, secured him in that position with slings, and removed the ascender he wasn’t weighting. She then ascended her rope back to the ledge and rigged a simple haul system. She’d done six big wall climbs in Yosemite Valley, Zion National Park, and Pakistan. She had trained with Britain’s Mountaineering Instructor Award program, including a full day working on rescue techniques. She knew what to do. But would it even be possible?

Bull rigged a standard “Yosemite haul,” with which climbers haul bags on big walls, but without all the gear you’d normally use—no pulley, no mechanical advantage. She ran the haul rope through a carabiner clipped to the anchor and attached herself to it using a prusik. She clipped the ascender she’d retrieved from Pritchard to the anchor and attached it upside down to the haul rope, so it would capture any gains as she hauled.

Bull weighed about 126 pounds at the time. Pritchard weighed 147 pounds, but adding his climbing gear, wet clothing, and the weight of the rope, Pritchard and his kit outweighed Bull by at least 35 pounds. Rick Vance, technical director at Petzl America, ran the numbers and estimated that, with all the inefficiencies in this system, Bull had to apply 225 to 250 pounds of force to move Pritchard. Even pulling up on the rope as well as down, she must have hauled at least 100 pounds in addition to her body weight with each and every pull, in order to gain every single inch.

The 100-foot haul took three hours.

Bull has forgotten some of the details of that day, or perhaps buried them (“It was really awful,” she says now), but months after the accident she told Pritchard, “I remember the deep wounds in my hands from pulling so frantically on the rope. I remember my back hurting like hell where the harness dug deep, bruising my waist. I know there are ways I could have done it faster, but this way was ingrained in me. I knew it worked as long as I had the brute strength in me.”

However much it hurt, she says now, “I never despaired. I had a lot of confidence that I was strong and that I could do this.”

As Pritchard neared the midway ledge, the angle of the rope and friction ground Bull’s effort to a halt. She scolded him, “You’ve got to help me here if we’re to get you out of this!” Pritchard struggled to comply, but his right limbs wouldn’t respond—his leg felt “like a piece of wood, a cricket bat, for instance, being knocked on the edge of a stone tabletop.” With his left arm and leg, and with Bull’s help, he desperately flopped onto the ledge.

Bull secured Pritchard to the anchor, lay him on his side in case he vomited, and headed for help. He would be on that ledge alone for seven hours.

Bull jumared to the top of the spire, made the Tyrolean traverse, and ran toward a campground five miles away, covered with Pritchard’s blood. Along the way she met some climbers hiking out to see the Totem Pole and urged them to go to Pritchard and comfort him, even if there was nothing they could do for him medically. Neale Smith, the only paramedic on Tasmania with climbing skills, happened to be in the area, and once Bull raised the alarm, Smith hurried to the Totem Pole, crossed the Tyrolean traverse, rappelled to Pritchard, and began administering first aid. There was no way for a helicopter to pluck them from this precarious spot, so they had to rappel together to a rescue boat in the channel below the tower. The tiny aluminum boat transferred Pritchard to a helicopter, which flew him to the hospital for surgery and what would become several months of rehabilitation.

Over and over throughout the ordeal on the Totem Pole, Bull, then in her early 30s, urged herself to “slow down, breathe.” She knew that if she had any hope of saving her partner, she would have to do everything just right. Bull now lives on the Scottish island of Eigg with her son, where they raise animals on a croft, or small farm. She also captains a 52-foot sailboat for tours and charters. Clearly, she has a farmer and sailor’s (and skilled climber’s) ability to adapt and make do with the tools at hand—characteristics she put to great use on the Totem Pole, along with her training and wealth of experience. She no longer climbs, however. “I stopped soon after the accident,” she says. “I lost the passion. I was just scared all the time.”

Pritchard and Bull, dating at the time of the accident, broke up while he was recovering, though they remain friends. He eventually married one of the nurses who helped him recover. His right side is still paralyzed, but he has worked out how to climb. He has written three books about the accident and his life afterward with hemiplegia. The first of these, The Totem Pole and a Whole New Adventure, won the 1999 Boardman Tasker Prize. An excerpt of his most recent book The Mountain Path can be read here.

Survival Tip: Focus on Life-Threatening Injuries

After a traumatic fall, the most immediate life threats can be remembered as ABC: Airway, Breathing, and Circulation (pulse and profuse bleeding). Read our basic first aid step-by-step checklist.