On 20 October, in a joint sitting of parliament, Mia Mottley, the prime minister of Barbados, described the removal of Queen Elizabeth as the head of state and the decision to become a republic as a “seminal moment” in our country’s history. We have reached the day that this becomes a reality, as Barbados embarks on its new path, cutting the umbilical cord that bound it to its former colonial master, the United Kingdom.

It begins on Monday evening, when Dame Sandra Mason will be installed as the first president of Barbados. That event, at which public participation will be extremely limited due to Covid protocols, but which will be beamed across the internet, will have the Prince of Wales in attendance as representative of the Queen.

That decision has itself stirred emotions. Some Barbadians will protest at his presence. Others suggest that now may be a good time to raise the issue of reparations with Charles.

In any case, this day has been a long time coming. It was on 14 May 1625 that the first English ship reached the island under the command of Captain John Powell, who claimed it on behalf of James I. It was from that time, 396 years ago, that “Los Barbados” (the bearded ones) became an English colony. It acquired its name from the Portuguese, earlier visitors who some claim were struck by the abundant fig trees, which have a beard-like appearance. Others surmised it was down to the presence of bearded people.

From 1627, the English settled on the island, wiping away any traces of the original inhabitants, the Arawaks, who had lived here for centuries. People with good financial backgrounds and social connections with England were allocated land in this new colony; Barbados’s strong connection and staunchly British attitude earned it the title of Little England. The English turned Barbados into a slave society, a slave economy, which would be replicated in several parts of the “new world”. It was known as the “jewel in the crown” of the Caribbean. It is a history that we can never be proud of, but one that we must understand.

Prof Hilary Beckles, a Barbadian historian, the current vice-chancellor of the University of the West Indies and a leading figure in the push by Caribbean islands to secure reparations, sums it up best. “Barbados was the birthplace of British slave society and the most ruthlessly colonised by Britain’s ruling elites,” he writes. “They made their fortunes from sugar produced by an enslaved, ‘disposable’ workforce, and this great wealth secured Britain’s place as an imperial superpower and caused untold suffering.”

Barbados, this beautiful island known today for its social amiability and political civility, has truly had a tumultuous history and a painful legacy, which still haunts us. But this has not prevented the nation, as Kofi Annan, the former UN secretary general, once said, from “punching above its weight”.

We see it as a journey: 30 November – when we become a republic – is another stop on our journey. It’s a date with resonance, as 30 November 1966 was independence day. It is a sign of this journey continuing that at 55 we are confident to say to the UK and the world that, despite our size and our limited resources, we can be our own shepherds, our own stewards.

Of course, our transition may not find favour among those whose view remains that the “sun will never set on the British empire” and that Barbados should always remain Little England. Older folks here remember the days when British royalty would visit. They would stand in the sun waving the union flag, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Queen or her representatives. But Little England has grown up, it has matured, it should no longer be loitering in its “master’s castle”.

As part of the transition, there will be ceremonial activities in National Heroes Square in the capital city, Bridgetown, but one notable absence will be Lord Nelson. For 208 years his statue stood in that square but in 2020 it was ceremoniously removed – a result of the Black Lives Matter movement here and the reawakening of our consciousness.

There are no plans to change our national symbols: the flag, the coat of arms, the national pledge, the national anthem. But the terms “royal” and “crown” will be removed from official terminology. The Royal Barbados Police Force will be the Barbados Police Service; “crown lands” will become “state lands”.

Independence day will still be on 30 November, but the focus will not be this event. The day will belong, as it always has, to our national hero, our first prime minister, the father of independence, the Right Excellent Errol Walton Barrow.

Of course, Barbados will maintain a strong relationship with the UK. Our main source for tourists is from there; Brits love Barbados. But this is a new era, in which all Barbadians must take pride and take ownership. As for Little England, these times may call for a new term of endearment.

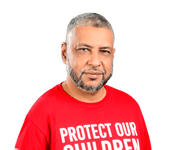

Suleiman Bulbulia was a member of the republican status transition advisory committee in Barbados and is a columnist for Barbados Today