Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Before Nirmal “Nims” Purja came along, the fastest known completion of all 14 8,000-meter peaks was seven years, 10 months, and six days—a record established by South Korea’s Kim Chang-ho without supplemental oxygen in 2013. After Nims Purja, the record is six months and six days—a time that even with oxygen (which Purja used) is going to be hard to beat.

A new Netflix film, 14 Peaks: Nothing is Impossible, directed by Torquil Jones and executive produced by Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi (of Free Solo fame), chronicles Purja’s blitz across the Himalaya, which he called “Project Possible 14/7,” while also contextualizing his accomplishments in the wider story of his life.

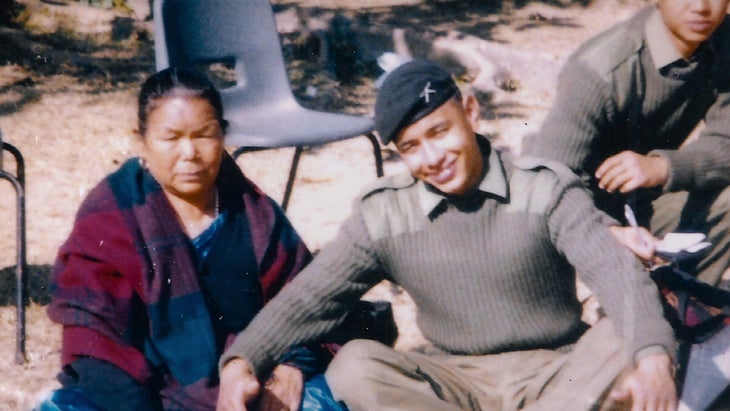

Purja was born in Nepal’s lowlands and grew up aspiring for a life in the military, not the mountains. In 2003, at the age of 18, he joined the Gurkhas—a Nepali unit within the British Armed Forces. Six years later, he became the first Gurkha in history to be accepted into the Special Boat Service (SBS), one of the UK’s most elite military units. After multiple tours, Purja eventually became a specialist in cold-weather warfare, which gave him the opportunity to pursue his interest in mountaineering. But in 2018, he decided to retire from the military and pursue another goal—that of climbing all 14 8,000-meter peaks in less than seven months.

Though relatively unknown in the mountaineering community when he embarked on Project Possible in 2019, Purja had already tested his mettle in the big ranges and realized that he was well-suited for high-altitude climbing. In 2014, during a brief leave from the military, he summited his first 8,000-meter peak, Dhaulagiri. He summited Everest for the first time in 2016, and then again in 2017, while leading the 13-person Gurkha Expedition, which celebrated 200 years of Gurkha contributions to the British military. A week of partying later, he upped the ante and returned to the mountain, this time summiting Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu (the world’s first, fourth, and fifth highest peaks) in a five-day period, a record that he later shattered during Project Possible, when he summited all three in 48 hours and 30 minutes.

Calling his dream “Project Possible” was a way of refuting the constant skepticism Purja encountered before starting. As it turns out, the biggest impediment to the project wasn’t the mountains or the weather or the limits of the human body or even last-minute permitting issues: it was financing. For nearly a year, Purja struggled to convince investors that his goals were realistic and that he was the climber to achieve them. When he finally kicked the project off by climbing Annapurna, on April 23, 2019, he’d secured only 15 percent of the total funding he needed—and most of that money came from remortgaging his house.

But Purja and his Nepali teammates soon turned heads. On May 24, barely a month after summiting Annapurna, he finished the project’s sixth 8,000-meter peak, Makalu. The donations—and well-wishers—began pouring in. And despite some last-minute permit drama and a few high-stakes rescues, Purja finished the project on Shishapangma, in Tibet, in late October.

Since 2019, Purja has remained a leader in mountains and a role model for the Nepali climbing community. In February 2021, he led the all-Nepali expedition that made the first winter ascent of K2, one of the most coveted objectives in mountaineering and the last of the 8,000-meter peaks to see a winter ascent. (Purja alone among his team summited without the use of supplemental oxygen.) He also runs a guiding company—Elite Exped—and is involved with a number of social justice issues, including the historical inequality of pay and benefits experienced by Gurkhas and Gurkha veterans.

Climbing spoke with Purja and the film’s director, Torquil Jones, over Zoom, while they were in New York City’s Netflix offices promoting 14 Peaks: Nothing is Impossible. We talked about the editorial challenges of cramming 14 peaks and a life story into a 90-minute film, about the financial challenges Purja faced going into the expedition, about mountain logistics, his military experience, and his excitement about the next generation of Nepali climbers.

14 Peaks: Nothing is Impossible will be released on Netflix on November 29, 2021.

*

Climbing: When did you first come up with the idea of doing all 14, 8,000-meter peaks in a year?

Purja: It was in mid 2018. I was the head of extreme cold weather warfare within the SBS. That means my job was to learn about climbing—the new technology, the new ideas—and bring it into the service and pass it to the guys. So I asked the service, since I had a lot of days off, whether I could go and climb the world’s five highest mountains in 80 days. At first, they got excited, but then they did the research, and they were like, “Hell no.” It was too dangerous. Nobody was prepared to take that risk. That’s when I decided to leave my special forces career and pursue a different purpose in life. And once I’d quit, I was like, “Well, I don’t need to do just the top five, and I don’t need to cram it all into 80 or 90 days.” I had the time. So I just said, “You know, let’s climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks. And let’s do it in seven months, because ‘Project Possible, 14/7’ sounds cool.” Everything has to be cool. [Laughs]. So, yeah, that was the concept.

Climbing: And you spent about a year preparing for it?

Purja: Well, I spent a year fighting to raise the money for it. There was not much fitness. Most of my time went to trying to tell people that “It is a great idea, and you should be part of it, and can you give me some money?” But everyone was like, “Who even are you? The previous record is nearly eight years, and you want to do it in seven months? Are you on crack or something?” So, it was tough.

Climbing: In the film, it sounds like you ended up having to serve as your own funding mechanism. Did you have any outside support?

Purja: I believed that the project was so huge that it was beyond the imagination of most people. But I also believed that once I started climbing those mountains in the style and in the manner that I said I would do it, people would start giving a little bit of money here and there. When I flew from Heathrow to Kathmandu, after remortgaging my house, we had some funding— but it was only like 15 percent of the total funding required. So yeah, it was pretty crazy.

Climbing: What about the physical preparation? You were fit from the military already, but a lot of people do six to eight months of specialized training to do just one or two 8,000-meter peaks.

Purja: I didn’t really do any training. I was about 10 kilos (22 pounds) above weight—mostly from the stress of writing emails and everyone saying no—because I knew that without funding there was no way I could do it. But I also knew that as long as I had a bit of money, then I could pick up my fitness as I climbed.

Climbing: On both your first and third mountains you had to participate in high-altitude rescues, and on mountain two, Dhaulagiri, you had some terrible weather. Were you having any second thoughts after the first three were so difficult?

Purja: I was like, “Yeah, bring it on.” That’s kind of the attitude I have. I love the challenges. For many people, when the weather is bad, they go down, but I go up… But it’s all calculated risks. I feel like, “Come on then, let’s keep going,” you know? Dhaulagiri, with the wind, was really crazy weather. We’re talking about 60 to 70 kilometers per hour (37 to 44 miles per hour). But I really love those challenges.

Jones: Just to add, the crazy thing for me—and we tried to show in the film by using the timestamp graphics—was just how compressed the timelines were. The guys did Dhaulagiri, and then two days later they were on Kanchenjunga, and then three days after that they’re on Everest, then Lhotse, then Makalu. Especially in that first phase, the speed was just off the scale.

Climbing: On that note: In the film, Nims, you acknowledge that these mountains are hard—that they’re hard for you and they’re hard for everyone—but most people are like the walking dead for a couple of weeks after just one peak, yet you’re able to do them back-to-back-to-back. Can you comment on that?

Purja. Well, you’ve got to roll into it, brother. You’ve got no other options. [laughs]. But you are right. Even my friends from special forces, when they came and climbed Everest and they’re like “Damn, Nimsdai, it’s been nearly two months and I haven’t even recovered properly: How the hell do you climb those three mountains back-to-back in 48 hours?” So, yeah, as I was saying to Torquil earlier, we should get some scientist to do tests on me. [Laughs].

Jones: That’s something that got me from the beginning. Not to speak of him like he’s not in the room, but Nims is pretty unique in the sense that he has both the right physiology and this extreme mental toughness from his special forces training. I think he planned the expedition like a military operation. Having those two things—the mental and the physical—working simultaneously is why he could do it so quickly.

Climbing: Nims, what about your decision earlier in life to join the military? Was that something you always knew you wanted to do?

Purja: I’ve always known what I want to do [next] with my life. As a kid, I wanted to join Gurkhas. That was my only dream. When I joined the Gurkhas, I found out about the Special Boat Service, and that was my only dream. And after that, I just wanted to completely change the dynamic on 8,000-meter peaks—and that became my dream. So yeah, it’s always specific. But one thing that all these dreams have in common is that I follow them.

Climbing: One thing that militaries—at least the good ones—are renowned for is their logistical prowess. How were you planning during that first phase and what are some things that a lay observer doesn’t necessarily think about?

Purja: One thing that’s important to note is that my planning was based on my ability and the ability of my team. We know for instance that if the wind speed is up around 60 or 70 kilometers [per hour], we can go through it, so we plan on it. Every risk that we took was calculated. But the bigger thing, in planning, is understanding the team dynamic. You need to understand who is strong in what points, who is weak in others, and then support the one guy’s weakness with the other guy’s strength.

Jones: When you’re climbing all these peaks back-to-back, the risk factor goes up massively. Take Kanchenjunga, for instance. Because the team was slower on Dhaulagiri because of the weather, they flew straight to Kanchenjunga and had to do it that day, in one summit push from base camp, because there was more bad weather coming. So the risk factor went through the roof by trying to line them up so quickly.

Climbing: When did you enter the picture, Torquil? And how did the filmmaking logistics get worked into the climbing?

Jones: I was introduced to Nims once he completed phase one [the first six peaks]. He was back in the U.K. raising more money to go to Pakistan, and we hit it off. Once he finished, we talked about what he had filmed and how a documentary could be structured around the 14 peaks. Nims did all the heavy lifting in terms of the film production. My role was to take the hundred-plus hours of footage that he’d shot and then add a layer of interviews, other mountaineering footage, historical archives, 3D graphics, and animation in order to contextualize the climbing. The real challenge was how to fit 14 peaks into 90 minutes alongside Nims’ backstory.

Climbing: It must have been a huge challenge cramming that much material into such a short period of time. How did you manage that?

Jones: Because it was all going through the prism of Nims, it meant we could do chapters. For instance, the whole Everest chapter revolves around the photo Nims took, the one that went viral [see below]. Once you talk about the picture, you don’t need to talk about the specifics of Everest again, since it’s been done a million times. With each mountain it was about finding its specific story. And when you actually laid them down chronologically, you’re like OK: on mountain one there’s a rescue; on mountain two, there’s a storm; on mountain three, there’s a nighttime rescue, and Nims runs out of oxygen; on Everest, there’s the traffic jam and the photo. There were unique aspects to each of them.

Climbing: Was that the most challenging part of making this film?

Jones: I mean the compression was the biggest challenge: How do you cover all 14 peaks while also doing justice to Nims’ life story, which is equally remarkable. The challenge was interweaving those two narratives. Plus we wanted Nims’ motivations to do the project—the Nepali representation, the human endeavor, and also his relationship with his family, his mother in particular—to become the big narrative arcs of the film. So allowing those three themes to develop—from a storytelling perspective that was the biggest challenge.

Climbing: Nims, your approach to these mountains is quite unusual. Can you walk me through one of your climbs?

Purja: It’s only relatively recently that people realized that you could climb multiple mountains once you’re acclimatized. But of course, you need to factor in the recovery time. Most people—probably 95 percent of the population—can’t recover fast enough [to take advantage of the acclimatization]. But for me, somehow, I can summit K2, come directly back down to basecamp, not even sleep the whole night, and then go to Broad Peak directly in the morning. But also, for me, I had the team. The bottom line is, we [Nepali climbers] can’t compete with our Western friends on technical 6,000-meter and 7,000-meter peaks, but 8,000-meter peaks are our home, it’s our playground. No one is better than us, you know? So we had this team of machines who knew how to work together and managed to have a good sense of humor. And slowly, especially by the end, the team started believing in the project. Because at first my team was like, “Fucking hell, it’s not possible.” Even all the Sherpas were like, “This is crazy.” So I think what I take pride in is imagining all this in the first place—because it was beyond imagination. No one had imagined it was possible. I didn’t even imagine it until in 2017, when I climbed Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu in five days. And that was stopping for two nights and partying in between. So it’s a blend of all that stuff.

Climbing: How did your team do? Minga David Sherpa was planning on doing 10 peaks during the project. Did he end up doing them?

Purja: Yeah. Mingma David is now the youngest guy in the world to climb all 14 8,000-meter peaks. Another member of the team, Geljen [Sherpa], he’d climbed only two 8,000-meter peaks when he started, and now he has only two of them left. Everyone on my team had a massive year. The big thing was that I was the one who was raising the money and they were getting paid. None of those guys could raise the money; I was able to do it because of my background in the special forces. But for them, it was work, it is their work, and they had to get paid for it. And now all of them are getting paid more than they were, because they now have name and brand recognition. So yeah, it’s just super cool.

Jones: It’s worth adding that the guys were guiding on some of the mountains while they were doing the 14. They needed the money. So not only were they going at speed for the record, but they were also having to be responsible for clients at the same time, which I thought was extraordinary.

Purja: I love supporting people to achieve their new possible. Recently, through my guiding company, we had three women who had never trekked before, but they talked about trekking to Ama Dablam base camp—and then, once they got to Kathmandu, they said “Nims, we want to climb.” So I said, “Well, who am I to tell you that that’s impossible; look, if you want to do this, this is what we need. I’m going to give you mission-specific training, and then we go.” And they all summited Makalu and made it back down to basecamp safely. Because who am I to say no to people? Who am I to say you can do this but you can’t do that? Only you know your limitations. For me as a guide, as long as I can serve as a safety net, people should be able to push their limitations. But I think that’s also why people started hating me. People say, “Oh, you need to go do these schools and climb this mountain,” and it’s like five years before you can even try Ama Dablam. But if people are fit and they can pick up the things, why not let them try? The bottom line is we should be able to adapt and take in. We should be more open-minded.

Climbing: Are you guiding full-time these days?

Purja: Yeah. I have a company called Elite Exped, and it’s my baby, that’s where all of my energy goes at the moment.

Climbing: Do you have a favorite mountain to guide?

Purja: I love Ama Dablam. It’s so technical and the ridges are so good. You never get bored there.

Climbing: One of the things that I find really interesting about this project is that when you first vocalized your dream, people scoffed at it. They didn’t believe it was possible. But then once you started, once the project wasn’t so abstract, people started getting psyched and supporting it.

Purja: When I started, most people didn’t even know who I was. Coming from SBS, I had no Instagram, no Facebook, no social. So when I said I was going to do this, they’re like “Who is this mad guy? Does he even know what it takes to climb one 8,000-meter peak?” But then we started climbing and people started looking into it, we started getting support, and it started coming together. I often say it wasn’t my project—it was the people’s project. So many people played a role in some form, from getting the political permission to go to Shishapangma to giving five or 10 pounds here and there.

Climbing: The Shishapangma thing was really interesting. You knew going in that China had closed the mountain?

Purja: Yeah. There was an accident in 2014. And after that they closed the mountain. They do whatever they want, you know. But I didn’t really worry about that at first. I was kind of like “I’ll deal with it when we’re like three months away from it.” We started getting the right people together, finding out who has good connections with the Chinese government.

Jones: It was too much detail for the film, but they were close to shutting him down even at basecamp.

Climbing: Once China had already approved it?

Jones: Yeah. They were at basecamp about to go up and someone from the Chinese government showed up.

Purja: They were like, “Nims, you can’t go up. The weather is too extreme.” And I was like “Come on, please.”

Jones: And as the film shows, there was a real groundswell of support from the mountaineering community, and that was a big factor in getting the Chinese government to be like, “Oh, OK.”

Climbing: The film talks about how you got some criticism from certain members of the mountaineering community about your use of oxygen. Can you talk about that?

Purja: Okay. So two things. I have done both. I’ve climbed without oxygen. I did K2 in winter without oxygen. And I’ve led expeditions on Manaslu without oxygen, Dhaulagiri without oxygen. If you are following the people who are setting up the lines, it’s easy. But even if you are using oxygen, if you’re trailblazing or fixing the lines, that’s way harder. I’ve done both—I can talk to both experiences. But some people have to talk people down to make themselves feel or look good, and those are the people criticizing. But saying and doing are different, brother. There will always be haters. It’s OK.

Climbing: You’ve become the public face for a new generation of Nepali climbers who’re out there kicking ass in the high mountains. What do you see as the future for the Nepali climbing community?

Purja: I think it’s going to be pretty cool. This project has opened the eyes of many in the Nepali climbing community. To keep it very simple: For me to wear the Red Bull hat—it’s important. People in Nepal see that. And now, with this movie coming out, people see what is possible for them. For instance, I only learned about SBS when I joined the Gurkhas, but now people will know about it—they will see that it’s an option. I hope it will be an eye-opener for many people, not only for people in Nepal but for young kids and people around the world. I hope they will see that as long as you believe in your vision and you go for it, you can accomplish things that seem impossible.