“I [patroller’s name], do swear, that I will as searcher for guns, swords, and other weapons among the slaves in my district, faithfully, and as privately as I can, discharge the trust reposed in me as the law directs, to the best of my power. So help me, God.”—Slave Patroller’s Oath, North Carolina, 1828

One lonesome late night in Brooklyn, I sat grading essays in my crib when outside my door I heard a cacophony of gruff voices, a little squad of shuffling feet, and swift seconds later a KABLAMKABLOWKABOOM on my door. Since I believed my apartment building was at least semi-secure, I crept over and answered with only mild anxiety. Whoa! There stood a phalanx of white dudes in the dim hall, some wearing jackets with insignias, others dressed in plain clothes.

“You live here?” one of them asked.

“Yeah, I do,” I said in feigned-ass aplomb.

“We’re looking for a suspect,” one of them said.

“Oh,” I said, and felt my mind leap to a battery of possible outcomes, none of which boded well for me.

“ID,” one said. “We need to see some ID!”

➡ For unlimited access to the most important stories for runners, join Runner's World+.

Let me remind you that I lived in a secured apartment building, that I had done no more wrong than maybe scrawl too few comments on a weak paper. Not to mention, none of these men had identified their official affiliation or produced a badge. Those facts, however, did little to beat back all the stories I’d heard of mobbish white men dragging Black folk—under cover of night or broad daylight, no matter—out of their homes to harm them out of the land of the living. In short, I knew full well the avid platoon at my door had the power to alter my life for the worse.

Because I was Black. Because they were white and could’ve been some Taneyesque “no rights which the white man was bound to respect” kind of 1-time. Because somewhere there were databases that labeled me a former felon, the same cached info that disqualified me from jobs and later housing, the same ones that would get me yanked into airport and Amtrak anterooms to answer umpteen questions. Because of all those reasons and then some, I fetched my license and stood in my threshold, heart humming like I’d just run a marathon.

One of them radioed my info. He slapped my card in his palm a couple of times—as if judging whether to trust the static reply.

“Anybody else in there?” he asked.

“No, sir, just me,” I said, and felt like a puredee sucka for using an honorific.

“We need to search it,” he said.

Search. And that’s when I couraged up a “No.” And said it firm too, like I meant it, when truth be told, it was at least half a punk-ass question. Said not from believing I owned the authority to refuse, but more so trepidation over what might happen if I assented.

No cap, a silence the length of old Pheidippides’ legendary run stretched between us before dude returned my license with a scowl.

That night remains a reminder how precarious my freedom was/is, of the fact that white men who were official officers or even those but law adjacent, owned an outsized influence over my supposed inalienable rights.

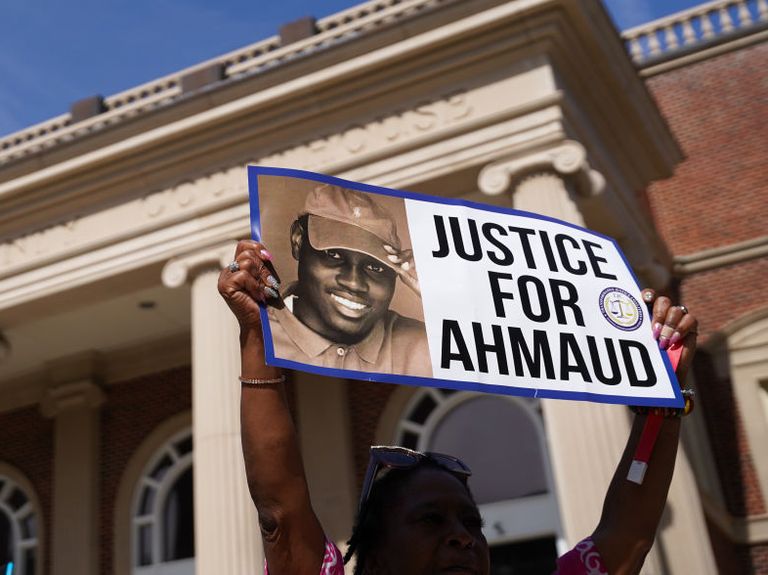

That was about 15 years ago. Before Travyon. Mike. Tamir. Sandra. Philando. Breonna…before I wrote about the life and death of Ahmaud Marquez Arbery for this magazine. On February 23, 2020, three white men—Travis McMichael (35), his father, Gregory McMichael (65), and attempted-to-turn-state’s-evidence accomplice William “Roddie” Bryan (52)—ceased Maud’s young life.

Their trial. We ought to know better, us folks who bring the news, and though I’d wager almost all do, that ain’t stopped legions from maligning Maud’s name. Though the simple answer is that its mischaracterization is one of the subtler means of ensuring perennial wins for whiteness—why oh why do I keep reading headlines and hearing reporters reference their proceedings as the Ahmaud Arbery Trial?

Maud ain’t the one on trial.

Maud’s the one dead.

The vigilante triumvirate is indicted on nine criminal counts including felony murder, aggravated assault, and false imprisonment. (In February, they will also face federal hate crime charges.) Their court proceedings should unerringly and irrevocably be referenced as the McMichael/Bryan Trial.

Repeat after me:

It’s the McMichael/Bryan trial.

The McMichael/Bryan trial

The McMichael/Bryan trial.

Maud was out for a run.

Jogging.

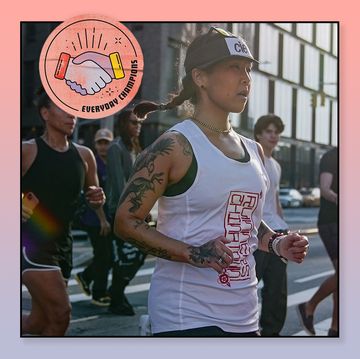

And what sport/pastime is more emblematic of America’s promise of liberty than jogging, than the prospect of moving free through these usurped lands? Running is both a literal and symbolic expression of America’s supposed ideals. And for that very reason, it’s a kind of fool’s gold for Black folks. A pursuit with the power to lure us into believing we just might own the same rights as white folks to pass through space unfettered, unbothered, unchastened—alive; that we, too, deserve the happy boost of a runner’s high to fuel our pursuits. The freedom to run is in part chicanery on account of Black skin having been cited over and over and over as probable cause for people who believe they are white (or close enough to it to reap its hegemonic yields) to limit our freedom, to restrict our possibilities, and the most extreme cases, to kill us with impunity.

The promise of running is ever part phantasmagoric for us because at bottom it requires justice—“the constant and perpetual will to render each his due”—a virtue that, since them first 20 and odd Africans touched Virginia shores, has been ultra, ultra undermined.

Check the records: Running has long been associated with Black liberty. Us running, running. From Dixie into the North. To the East. To the promise of the West. Absconding into Canada, Mexico. Beginning in the Carolinas in the early 18th century, white folks organized patrols to hunt, catch, and return us into bondage, to null even the inkling of a revolt. It takes little imagination to see the McMichael duo and “Roddie” Bryan as a neo slave patrol (nevernohow am I calling Maud a slave): men who deputized their damn selves to police Maud’s freedom, by any means, for any reason, at whatever the cost.

Please know that Maud’s killers did almost nothing to tend his wounds—per Bryan’s statement to investigators, triggerman Travis McMichael called Maud a “fucking nigger” while he lay dying. Know as well that when Glynn County’s finest sirened onto the crime scene, they proved simpatico. How else to describe that, while Maud’s bloody dead body lay just a few paces away, one cop spoke to his killer as if she was doing no more than inquiring about the weather: “I’m going to get you some stuff to clean up with alright, sir… That’s fine, that’s fine, just take a breath…You need to move around, do what you need to do, man. I can only imagine,” she said.

The McMichaels have claimed they believed Maud was a burglary suspect, but beyond that hella poor alibi is the inarguable truth that even average-ass white men such as them claim the right to, by any means, circumscribe Black life.

And that prerogative is on trial as much as the facts of this case.

As a matter of fact, that prerogative has won the day no matter the verdict.

Justice—isn’t that the point of any trial?

The philosopher John Rawls described justice as “the first virtue of social institutions,” and I’ll be damned if Maud’s death isn’t further proof (as if we needed more evidence) of how little that virtue has existed in our legal system.

The chief argument of the defense is Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law. While the concept of a citizen’s arrest dates back to medieval England, well prior to any formal police forces, Georgia’s citizen’s arrest law was established in 1863 as part of codifying its state laws. Peep that date. In 1863 Georgia was fighting on the wrong side of the Civil War. Plus, it’s telling that the law was championed by Thomas R.R. Cobb, a secessionist who, before being killed in the battle of Fredericksburg, was a vociferous supporter of slavery, so much so that he wrote a whole damn book praising it: An Inquiry into the Law of Negro Slavery in the United States of America.

And lest somebody claim a great distance between the paradigms of the confederacy and the ideals of the men who killed Maud, I point you to the fact that Travis McMichael drove a truck with a vanity plate displaying the old Georgia State flag, the one featuring a confederate flag as part of its design. Not to mention, he also decaled the toolbox in his truck bed with a Dixie sticker.

Who does that? Where?

You could also trace the absence of Rawls’s vision of institutional justice back to the outset of this case, when one white DA and then another allowed the McMichaels and Bryan to bop around the Golden Isles as unindicted free men for damn near 10 weeks. Can you believe it? Hell, if Bryan’s legal team hadn’t somehow figured it wise to release footage of Maud’s lynching, all three men might’ve skated unpunished forever.

A guilty verdict won’t change that.

We shout, BLACK LIVES MATTER. BLACK LIVES MATTER. BLACK LIVES MATTER.

White lives rule, they rebut.

And do it over and over again.

In their callousness toward Black life. In their refusal to hold themselves accountable for harming us. In their turning injustice systemic however they can. Take, for example, the malfeasance of empaneling one Black person on the 12-person jury that will decide the case, and this despite Black folks comprising 27 percent of Glynn County’s residents.

One Black.

Eleven whites.

That egregious algebra is secured by the prejudicial practice of peremptory strikes, a legal gambit used by lawyers to dismiss potential jurors. A lawyer can challenge the validity of a strike with what’s called a Batson challenge. But that challenge will fail if the judge deems it free of—the bar of proof is so low as to be absurd—religious, racial, sexual, or ethnic bias. Go figure, researchers have proven that these strikes are by and large grounded in those very biases, so much so that Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall once described them as “perhaps the greatest embarrassment in the administration of our criminal justice system.” Even the trial’s presiding judge, Timothy R. Walmsley, acknowledged their role in corrupting the trial. “There appears to be intentional discrimination in the panel. Quite a few African American jurors were excused through peremptory strikes exercised by the defense,” he said, but in the next breath he argued that the defense had met the burden of providing a “legitimate, nondiscriminatory, clear, reasonably specific and related reason” for striking each possible juror.

It’s essential—seeing Maud’s lynching as the singular tragedy it is, but as you might’ve gathered, I also believe that considering his death within its broad social and historical context is crucial. Those aims remind me of a conversation I had with Maud’s best friend Akeem (Keem) Baker, during which he reminisced on his and Maud’s runs across the Sidney Lanier Bridge. When I mentioned that Lanier was a confederate, Keem said he was unaware, acknowledged, too, that it surprised him. That admission was yet more evidence of untold ways white people secure themselves as the dominant caste, of how Keem and Maud and all us Black folks are subject to that dominion. In ways obvious and subversive. By means tried and novel. Beyond Keem, I spoke to Jasmine (Maud’s older sister), Shenice (the love of Maud’s life), JT (one of Maud’s childhood homeboys), and Buck (his older brother). Maud’s people were warm, kind, generous, thoughtful. Though each of them was grieving, our conversations were shot through with light, their voices perking with fond memories of Maud, reminiscences that often called up laughs. Matter of fact, talking with Buck, I laughed so hard my belly ached.

Not only was it clear in every conversation that Maud had touched each of his people in meaningful ways, I also considered each one of them a testament to the resiliency of our people, to the failure of white folks’ evil to snuff the good in us.

Without doubt Maud’s mother, Wanda Cooper-Jones, is an exemplar of that fortitude.

I’ve witnessed Wanda at rallies, somehow composed, with a gaggle of microphones punched at her face. Wanda in a New York Times video calling for Georgia to legislate a state hate crime law. (Can you believe the state whose 589 lynchings ranks second only to Mississippi had no hate crime law on its books at the time of Maud’s death?) Wanda in TV interviews, her voice measured and soft, her hue and distinctive front-tooth gap reminding me of Maud’s photos. Like Black mothers dating back to Mamie Till, here’s Wanda in the midst of unimaginable public misery, committed to securing from a blatantly, flagrantly, despicably corrupt legal system, even the chance to see white men punished for what they’d done to her son.

My story “Twelve Minutes and a Life” begins with an anecdote of Maud at football practice during his sophomore year. My son is a sophomore this year, which I mention because while I was traveling last month, his mother called me frantic with the news that a man had called him the n-word on his walk home from the bus.

We’d moved to Arizona a few months prior, and though I’m no expert on the racial history of the great state of Arizona, would it surprise you to know that I wasn’t surprised? My son and I chatted about the incident and the gist of my counsel was that he needed to be vigilant and also to let it serve as a reminder that there are people in this world who will hate him for no other reason than the fact that he’s Black.

In hindsight, I should’ve been just as spooked as his mama. Should’ve considered the prospect that, just as Maud had been killed for doing nothing more than jogging, my son had been imperiled skipping home from school; that it would take but a heartbeat to turn the unfathomable into a source of eternal mourning, for his mother and me and all else who love him to be drafted against our utter will into the bleakest fraternity on earth.

BLACK LIVES MATTER. BLACK LIVES MATTER, we chant; we shout; we plead.

Justice for __. Justice for __. Justice for __.

They scream, WHITES LIVES. BLUE LIVES. GREAT AGAIN.

Aver, “no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

They say, “We need to see some ID….We’re looking for a suspect.”

They say, “That’s fine, that’s fine…Just take a breath…I can only imagine.”

Announce, “There appears to be intentional discrimination in the panel.”

They mark us, hunt us, shoot us dead in the street. “Fucking nigger,” they seethe.

Mitchell S Jackson is a contributing writer for Esquire, the winner of a Pulitzer Prize and a National Magazine Award as well as the acclaimed author of the memoir Survival Math, and the award-winning novel The Residue Years.