With capital in abundance, SaaS startups don’t seem to be too worried about how much runway they have remaining.

According to OpenView’s annual Financial & Operating Benchmarks report, only 13% of nearly 600 companies surveyed named “burning too much cash” as one of their top three concerns, compared to 30% last year.

While 2020 was atypical and a rebound this year is not surprising, the report goes one step further, arguing that there is an increasing gap between the haves and have nots of B2B software.

Nowhere is this more apparent, the authors claim, than when you look at public B2B SaaS companies. In an analysis accompanying the new report, they point out data showing that some companies see their enterprise value increase much faster than the competition.

The combination of an enormous market, a compelling growth engine and outstanding unit economics is helping top startups attract talent and capital, which might increasingly be escaping lower-performing companies, according to the report’s authors.

“Investors have forgotten all about the Rule of 40.” OpenView Partners

But what does that mean for founders that aren’t anywhere near an IPO yet? And which benchmarks can they use to evaluate their performance? To find out, we talked to the report’s two lead co-authors, OpenView’s Vice President Sean Fanning and Operating Partner Kyle Poyar. We also reached out to Dale Chang, operating partner at Scale Venture Partners, which aggregates data of its own via its Scale Studio; and to Matt Cohen from Canadian VC firm Ripple Ventures.

Our conversations covered some of the strategies SaaS companies can adopt to emulate their top peers — including product-led growth and usage-based pricing, of which OpenView is a known advocate — as well as a lingering concern: Are the multiples we are seeing sustainable?

Measuring up

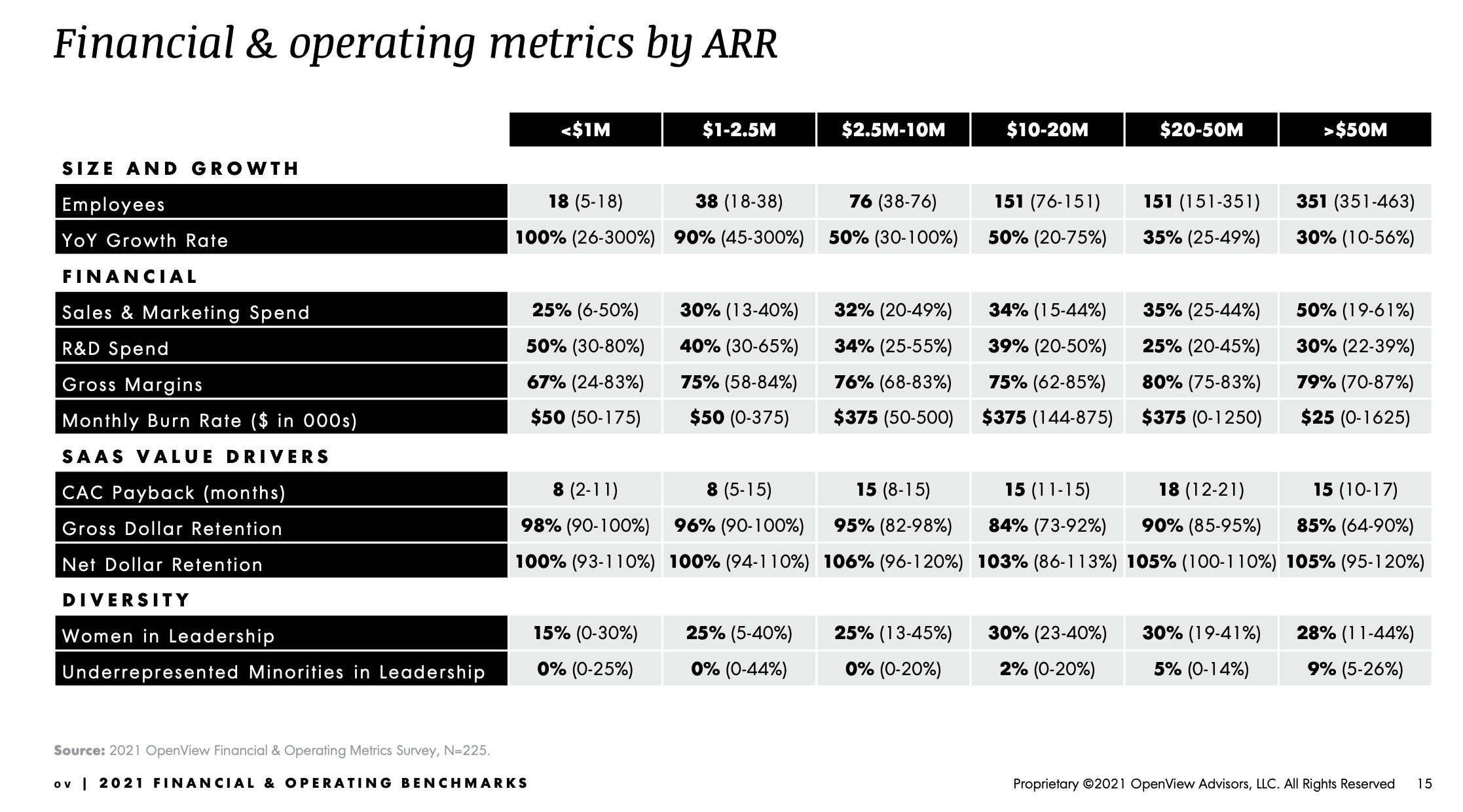

If we had to only retain one chart from OpenView’s report, it would be the benchmarks table below, which features a few metrics and separates them based on the respondents’ annual recurring revenue (ARR):

Image Credits: OpenView Partners

A note to readers explains that “each cell represents the median performance of a company, as well as the range (bottom quartile and top quartile) of each metric at each respective ARR scale” with the median in bold and the range in parentheses.

The authors note that “benchmarks are the map, not the territory” and that “performance and valuation are a multivariate equation.” Still, the founder of a startup with ARR between $1 million and $2.5 million might be pleased to see that growing 100% year on year means outperforming the average SaaS company in that category. But they will also note that top-of-class companies grow by about a whopping 300%.

All eyes on growth

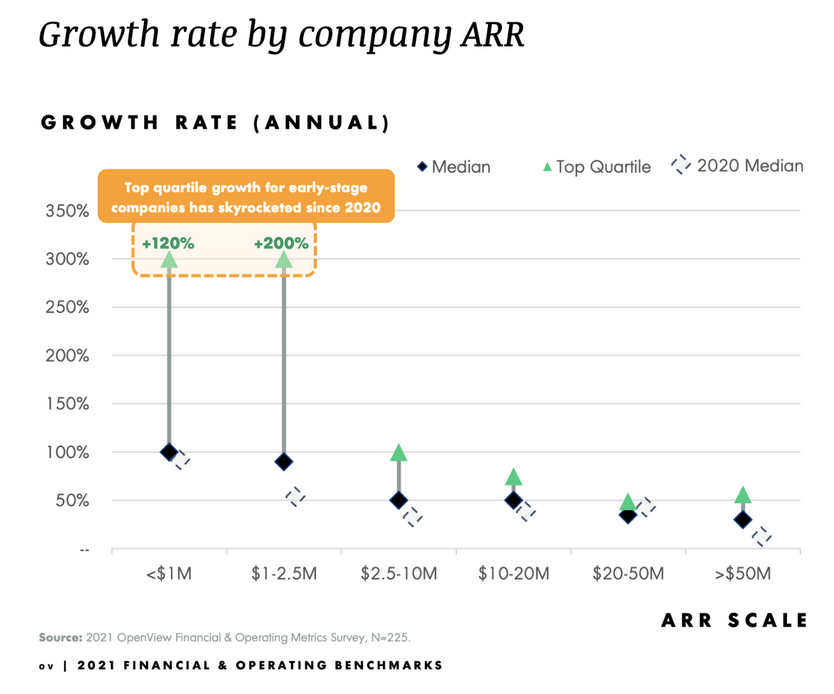

The median growth rate of SaaS businesses would already leave the average SMB in dismay, but the top quartile’s performance is on a different level, especially for early-stage companies. Just look at this chart:

Image Credits: OpenView Partners

It’s crazy how quickly early-stage companies are growing. Except for the $20 million to $50 million ARR range, median and top-quartile growth rates have risen across the board compared to last year.

Scale’s Chang corroborated this acceleration: “We have seen a broad increase in growth rates across the entire spectrum. One of the most pointed examples is in the early-stage set of data. Our data shows that pre-2021, the top decile growth pattern was to go from $1 million to $3 million (3x) in a year. We’re now seeing that top decile companies are able to go from $1 million to $5 million (5x) in the same time frame.”

With such metrics, investors are hardly paying attention to anything else, including to profitability. “Investors have forgotten all about the Rule of 40,” OpenView observed, referring to a VC trick that says a good company’s growth rate and profit should add up to 40%.

Now, OpenView says, it’s all about the Rule of 30: “30% top-line growth.”

This focus on growth was also confirmed by Matt Cohen. “With startup valuations ballooning, the 40% rule is currently far from top of mind for investors, whether in private or in public markets,” he said. “For better or worse, the focus at this point in time is almost entirely on growth given the low interest rate environment and easy access to capital that investors can leverage.”

However, even a few years ago, VCs weren’t necessarily demanding profitability from early-stage startups, which is perhaps where analyzing private and public companies at the same time is showing its limits. Are we really forgetting a rule if it never applied?

Indeed, Chang shared data that showed that companies with ARR below $500 million are usually very far from 40%, and companies with ARR below $25 million even fall in the negative. “However, as a company approaches scale and prepares for an IPO, the Rule of 40 becomes a useful benchmark,” Chang said.

A data-backed case for product-led growth

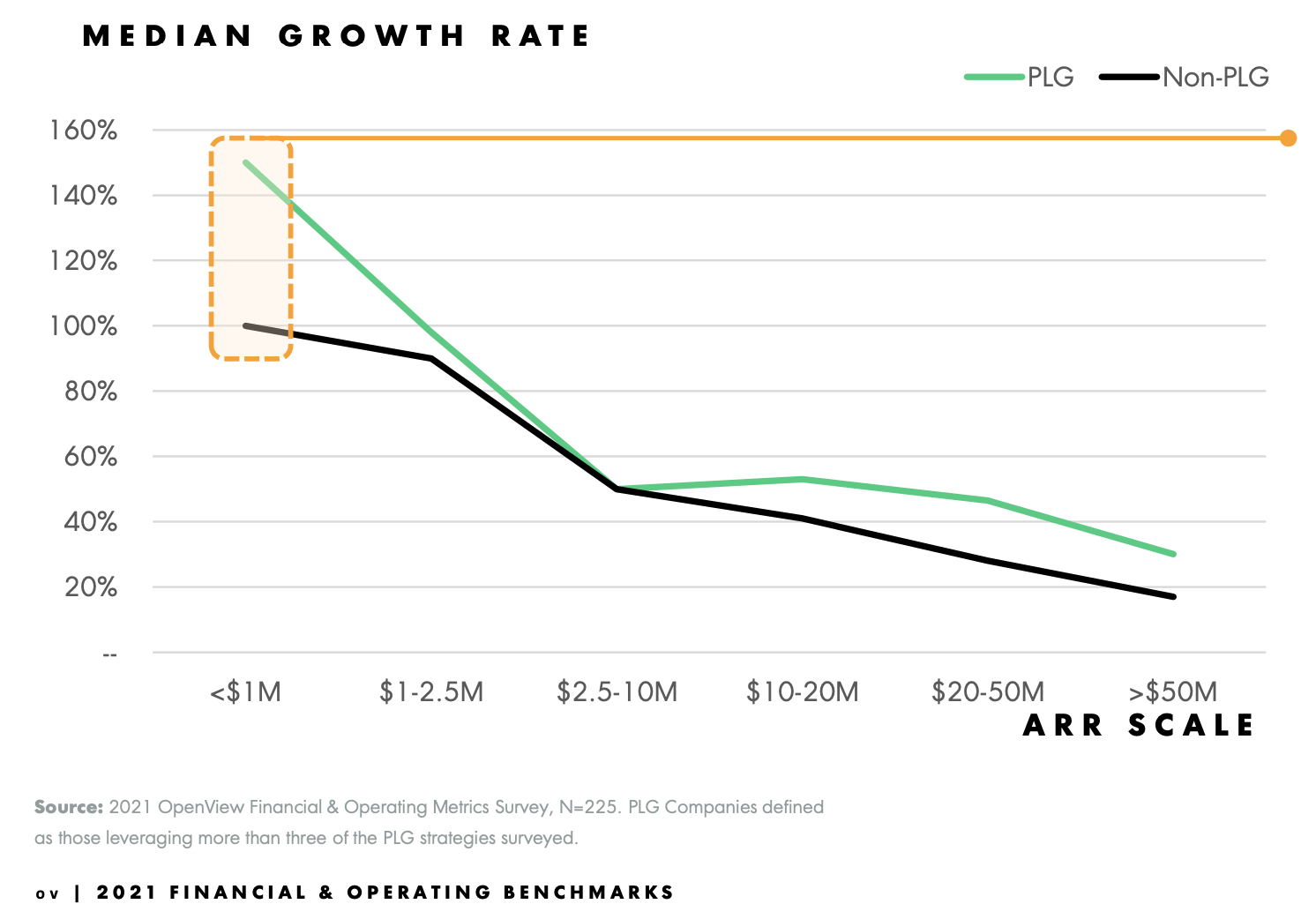

“We used to observe PLG companies growing more slowly than their peers at earlier stages; they’re now outpacing their non-PLG peers at all ARR scales,” the OpenView report’s authors noted.

This observation is based on the graph below, specifically on companies with less than $1 million in ARR:

Image Credits: OpenView Partners

Product-led growth used to be a trade-off in the early stages of a company until “the magic of the PLG flywheel started to kick in,” Poyar recalled. But with plenty of capital available and business models becoming more hybrid, it might no longer be the case.

Companies like Atlassian or Dropbox were almost uniquely self-serve in their early days, but many companies are now using mixed models, Poyar said, citing as an example OpenView portfolio company Cypress.io, which offers a testing framework for developers.

“They have a really healthy product-led motion, where folks find the open source product and then fall in love with it for their workflow […] Cypress has added more resources on marketing and sales as well to drive more awareness, to educate folks around the organization-wide benefits of rolling out the product as opposed to just the individual user benefits.”

This trend also explains why sales spend and product-led growth are no longer antithetical. According to the report, product-led growth companies “generate 1.7x more gross profit for every dollar of sales and product spent.”

It is easy to see why companies now don’t abstain from spending to further propel growth. “If growth is rewarded in the way that it is in the current market, there’s no downside for them, and it’s still productive spend,” Poyar said.

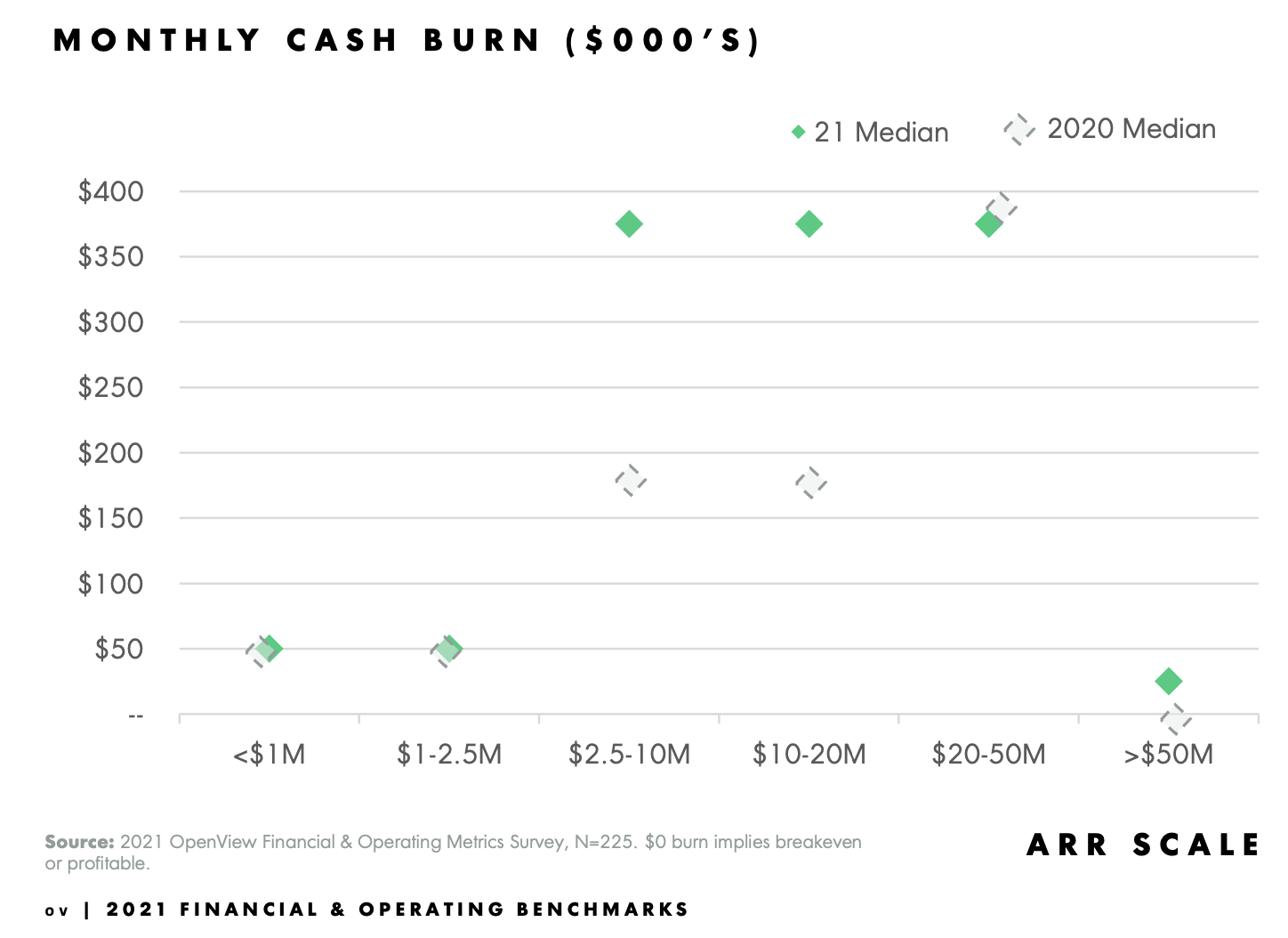

Cash put to use

It is impossible to separate what companies are doing from the overall VC climate. As a result of having access to more cash than ever before, the median monthly cash burn of companies with ARR of $2.5 million to $50 million has increased considerably from a year earlier.

Image Credits: OpenView Partners

For confidentiality reasons, Scale Studio uses operating income as a proxy for cash burn, but its data also point in the same direction.

“It’s a fact that cash burn was higher in 2021 (-45% median operating margin) when compared with 2020 (-33% median operating margin),” Chang told TechCrunch. “This is largely driven by the tightening of the belts we saw in 1H20. We saw a gradual build in confidence in 2H20 and aggressive growth re-acceleration in 2021. In fact, what we saw was nearly a return toward pre-COVID norms.”

Poyar and Fanning don’t have any issues with cash burn as long as it’s productive. “If capital is being spent to really create value for customers, then we’ve got no problem with it,” Fanning said. “If over the long term, you can generate sustainable cash flows, because customers need what you’re selling, then that burn is more than justified.”

Too fast to slow down

With cash less of a concern, hiring is now what keeps founders up at night. Poyar said fast-growing companies benefit from a halo effect and are able to attract great talent to double down on growth, while other companies are struggling or slow to hire talent that can help them meet milestones.

The risk of even temporarily veering off target shouldn’t be understated. “Even missing one or two quarters can slow a company’s growth trajectory down,” Chang noted, pointing to the compounding effect of growth. Below a certain threshold, he added, a company’s chances of attracting venture capital can get low.

This applies to private companies as well as to public companies boasting multiples in the double digits. With tremendous growth already priced in, these companies don’t have much margin for error. “They’re walking on a razor-thin edge. They have to execute and do exactly what they say, or the multiple will be too high, because the company won’t generate what investors expect of it,” Fanning said.

That sounds like something to worry about — maybe not for VCs with a varied portfolio, but for retail investors taking single stock bets. However, OpenView feels these expectations are largely warranted: “Best-in-class companies,” the authors explain, “marry the trio of big market, compelling growth engine and unit economics: telling a big story, nailing the execution and capturing market share efficiently.”

Fanning and Poyar highlighted another interesting trend: Many SaaS heavyweights have TAMs that are much larger than initially thought. For example, when Salesforce went public in 2004, its S-1 valued the market at $7.1 billion. Today, that estimate is less than the company’s revenue (it recently raised its outlook for fiscal 2022 to $26.3 billion.)

TechCrunch enterprise reporter Ron Miller says Salesforce used three key principles OpenView identified to surpass the $20 billion revenue goal that founder Marc Benioff set in 2017.

“Product-led growth, capturing swaths of market and nailing the execution, and finally, and this is important, building a culture of community and success where volunteerism and giving back is encouraged, as much as executing on the business side,” he said. “Perhaps it makes sense that the oldest and most successful SaaS company is a case study for everything that OpenView espouses in this report and a role model for every SaaS startup.”

The pandemic also played a role in some cases, Chang said. “With COVID pushing almost every sector through digital transformation, the markets that software can address are now both wider and deeper, which may explain some of the increased growth rates and valuation bullishness.”

From that perspective, double-digit multiples seem easier to justify. While sustaining extremely fast-paced growth can be something of a tightrope to walk, it is also a good problem to have.