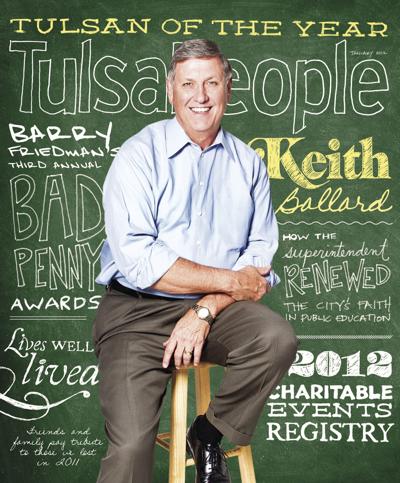

In 2011, the Tulsa Public Schools superintendent faced the most difficult undertaking of his career: tackling a much-overdue effort to realign the number of schools in the state's largest school district to eliminate costly and wasteful under-capacity issues that had crept into the system over time and restore academic equity.

The resulting initiative, Project Schoolhouse, closed 14 schools to eliminate thousands of empty seats and saved the district more than $5 million per year to reinvest in expanded and more accessible education opportunities for students. Learn why this brave and bold plan, and other leadership efforts to improve Tulsa schools, earned Ballard the honor of being named Tulsa People's Tulsan of the Year.

After nearly 40 years in education, Dr. Keith Ballard has never stopped learning. From his first job as a classroom teacher to his current post as superintendent of the state's largest school district, Ballard has continually sought knowledge.

Not just from formal education although he boasts three higher degrees but also from professional experiences, his personal life and gaining insight from those around him.

He often discusses his wife, Christie, a retired school librarian, who helped Ballard with the first challenge in his educational career teaching junior high students how to improve their reading skills. He says she has kept him grounded in his leadership positions, reminding him of the perspectives of classroom teachers, parents, and others his decisions affect. He is motivated by his three children Matthew, a lawyer; Michael, a high school assistant principal; and Michelle Andrews, an elementary school teacher who have driven his desire to make a difference in the world and with whom he maintains a tight bond.

Ballard cites pivotal experiences that have shaped him — from helping the OologahTalala school district recover from a devastating tornado to traveling around the state meeting with school boards as executive director of the Oklahoma State School Boards Association.

But when Ballard assumed the position as superintendent of Tulsa Public Schools (TPS) in October 2008, for the first time, he took the helm of an urban school district one with 42,000 students, 87 percent of whom live in poverty. It was a district that was facing severe budgetary challenges, declining morale from teachers and staff, and a loss of faith from people in the surrounding community.

And in 2011, Ballard faced what he calls his most challenging assignment yet, an initiative born of necessity but that would result in lasting benefits for the district Project Schoolhouse.

The unprecedented effort aimed to improve efficiency, equity, and effectiveness districtwide and involved a number of elements, including school closings, grade reconfigurations, and other issues that troubled school patrons. Yet Ballard believes it has resulted in positive changes for TPS.

In many ways, Ballard's entire career prepared him for Project Schoolhouse, and life lessons he learned and taught along the way reveal how this consummate student and educator helped lead the turnaround of a school system and affect an entire city.

Lesson 1: “If you don’t think about people and you don’t think about relationships, then you will not lead.”

In late November, Ballard addressed students at the newly renamed Will Rogers College High School, a program where students can earn a high school diploma and an associate’s degree simultaneously. There, he shared his story and how, like many of the students he was addressing, he overcame obstacles in pursuit of education.

He grew up in Kiowa, a small town in southern Kansas, he told them. His parents, he says, married at 17 and had three children by the time they were 22. Although he hesitates to use the term, Ballard says he grew up poor — his dad worked as the janitor at his school and his mother was a nurse's aide in a local hospital — but his parents did not let limited economic means keep them from encouraging their children to pursue their goals.

“It was instilled in me from a young age that education was extremely important, and I always knew that I would go to college, and I liked school and I liked learning,” Ballard says. With no financial assistance, Ballard worked his way through Fort Hays Kansas State University, where he majored in psychology and speech. By the end of his college career, though, he had decided to pursue a different path. A “product of the ‘60s,” Ballard desired a profession that would allow him to make a difference in the world. So he set out to become a teacher.

Another event also affected this decision. At age 18, Ballard’s younger brother, Joe, was diagnosed with cancer. He entered college battling the disease but died two years later just after Ballard earned his degree in 1971. His brother's death deeply affected Ballard, and he says it further motivated his desire to change lives.

“I was very intentional about I’m going to make a difference,” he says. “I just didn't know how I was going to make a difference.”

Fortunately, Ballard had found someone who shared his passion for teaching.

He met his wife, Christie, when the two were teenagers attending a WKY radio-sponsored “teen hop” in Kiowa. She was the daughter and granddaughter of teachers and, like Keith, “loved learning. I loved all subject areas,” she says.

The two married in 1971 and moved to Stillwater, where Christie was finishing her English degree at Oklahoma State University. Although Keith sent out hundreds of letters to find a teaching job, he came up empty and resorted to driving a freight truck, working in the back alleys of downtown Stillwater.

Upon graduation from OSU, Christie accepted an opportunity to work as an English teacher for Coweta Public Schools in northeastern Oklahoma.

The Coweta superintendent understood that hiring Christie would mean finding a position for her husband as well. He told Ballard that if he would take nine college hours of reading, he could become certified in the subject and work with Coweta’s junior high students.

“I’ll never forget him looking at me and saying, ‘Can you do that?’” Ballard says. “And I said with total and utmost confidence, ‘Absolutely I can do that.’ Then, when we left his office I said to my wife, ‘How do you teach junior high kids to read?’”

Ballard had to learn quickly, and while he says he loved learning to become a reading specialist, his experiences in the classroom were more difficult.

“I learned the only way to control 45 kids in class was to build relationships with them, and that’s what I did,” he says.

Lesson 2: “Do a good job where you are and prepare yourself for what could happen in the future.”

By 1974, Ballard had earned a Master of Education as a reading specialist when he learned that Oologah-Talala Public Schools was starting a high school reading lab. He applied and was hired for the job; Christie also earned a position in the district as a librarian.

During the summers in Oologah, Ballard began taking classes in school administration, eventually earning his administrative certification. At the time, he says, Oologah was facing controversy, resulting in the exit of the superintendent and other administrators. When a new superintendent, Lonny Parrish, arrived, he called in the then-27-year-old Ballard to offer him a position as an assistant principal and transportation director.

This opportunity, Ballard says, set the stage for nine years of work at the administrative level, in nearly every position possible, from federal programs director to head of buildings and grounds to athletic director.

As a result, when Parrish left, he recommended Ballard, then 36, to take his place.

It was in this position that Ballard faced a defining moment in his career.

On April 26, 1991, an F-4 tornado struck the Oologah-Talala school campus, causing $10.5 million in damage, the worst ever inflicted on an Oklahoma school by a natural disaster.

“It was a terrible, devastating event, a shocking event,” Ballard says. “I learned that you need to be prepared for a disaster, which we weren’t, so I learned the hard way of what it means to be prepared, and that really extends into all areas of really being prepared. You’re dealing with the public. You’re dealing with kids. You’re dealing with parents ... and they need to have confidence that someone is in charge who knows what they’re doing.”

In the aftermath, Ballard made more than 100 public appearances to discuss the disaster and the district’s recovery from it; he also made disaster preparation and recovery the subject of his doctoral dissertation.

Consequently, several Oklahoma school districts including nearby Claremore Public Schools contacted him about open superintendent positions. Although he was reluctant to leave Oologah after 18 years, Ballard felt ready to lead a larger district.

In Claremore, he found high-achieving students and a community that supported education. He says his family grew to love Claremore as well — Christie continued to work in Oologah, retiring in 2001 — and all three of his children graduated as valedictorians from Claremore High School. He still lives there.

“My time in Claremore, I would define that as a magical time for my family,” Ballard says. “... It was just a time that we loved. We really settled in, and I suppose that’s why I never left Claremore.”

Lesson 3: “If you don’t believe that’s what you’re meant to do, then don’t go do it because it will be extremely difficult. You can’t make all of the people happy, and you have to stay focused on truly making a difference.”

During his time at Claremore, Ballard became involved with education initiatives at the state level, serving as president of the Oklahoma Association of School Administrators and the United Suburban Schools Association, as well as helping form the Oklahoma Education Coalition.

In 2000, when the Oklahoma State School Boards Association was seeking an executive director, Ballard took the job and the opportunity to affect legislation and state policy.

Not wanting to uproot his family, he commuted to Oklahoma City from Claremore for the eight years he served in the position. He also traveled the state, training more than 125 school boards; worked closely with state leaders, such as Govs. Brad Henry and Frank Keating; and met with school board association directors from across the nation.

During this time, he also served as an adjunct instructor with The University of Oklahoma, which offered him an opportunity to finish his career as a professor there. By 2008, he had notified the association that he was leaving, but they convinced Ballard to stay another year. That's when he received a call he never expected.

During his travels around the state, Ballard worked with the Tulsa Public Schools board. When the board reached a settlement agreement with outgoing Superintendent Michael Zolkoski, members decided that rather than undergoing a national search, they would recruit a candidate.

They called Keith Ballard.

“His network throughout the state was incredible,” says Brian Hunt, a school board member at the time. “Not only did he know every administrator from across the state; he had an excellent relationship and was well respected by the state Legislature. He brought a skill set to Tulsa Public Schools that we had not had.”

Ballard recalls his reaction to the offer. “What I remember most about that is going home and telling my wife ... and she said, ‘Well, what did you say?’” Ballard says. “And I said, ‘Well, I told them I'd consider it.’ I'll never forget her saying, ‘You what? You said you’d consider going back into the superintendency? I thought you were going to OU to be a professor.’”

After a month of consideration, Ballard knew what he had to do. Nearing the end of his career, he wanted an opportunity to give back; he also wanted to honor his older sister, Connie, whose death at age 59 in 2007 “inspired my desire to make a meaningful difference,” he says.

Tulsa Public Schools seemed like a perfect chance to do both.

He became superintendent in October 2008 and quickly scored several successes, including contributing to Tulsa's selection as a Teach for America site in 2009 and helping secure a $354 million bond issue in March 2010 the largest school bond measure in state history.

By fall of that year, Ballard faced what he calls “the most difficult undertaking of my career.”

Lesson 4: “If you think that because you make it into a chair, you’re going to be the sole decision maker, you’re going to fail.”

By the beginning of the 2010-2011 school year, TPS was facing multiple major challenges:

In one year, the general fund had dipped from $364.8 million to $326.5 million.

State aid reductions required cutting 120 administrative and 225 teaching positions.

Federal stimulus funds financing the salaries of 250 employees were set to expire in September 2011.

Ballard decided it was time to take action — in a drastic way.

The result: Project Schoolhouse.

With the help of a professional consultant, a community advisory council and a “Blue Sky” panel of educators who had exhibited or led successful education reform efforts, Ballard aimed to assess all 89 schools in the district. The initiative would take into account demographics, facility utilization, community services, safety and other factors in an effort to reduce the number of empty seats in TPS and improve efficiency, equity for students and educational effectiveness overall.

Over six months, Ballard oversaw dozens of surveys, committee meetings and public forums to collect as much information as possible. Throughout the process, he says, he maintained the philosophies that have driven him from the beginning of his career: forming relationships with teachers and the community and keeping the best interests of students at heart.

“I’ve been through a lot of disasters and catastrophes and very difficult times in my career, and what always pulled us through those difficult times was the sense of family in the school,” he says. “And although it was a little difficult to get that in a district this size, we still rallied around (one another). We had great support from the community; we had great support from the teachers.”

In May 2011, the TPS board approved the Project Schoolhouse plan, which resulted in the closing of 14 school buildings to eliminate 5,600 empty seats and potentially save the district about $5 million a year.

Deputy Superintendent Millard House says he learned valuable lessons from watching Ballard lead the Project Schoolhouse process. In particular, he says the board meeting where the proposal was accepted proved Ballard’s effectiveness.

“To know that we didn’t have speakers lined out the door to speak against Project Schoolhouse; to know we had (groups) from the Chamber to individual neighborhood associations that may not have agreed but understood why these decisions had to be made it was a huge lesson learned,” he says. “It was almost like taking a class, being a part of the process. He was the perfect person to help lead ... that effort.”

The impact of Project Schoolhouse is already evident, House says.

“Now, we’re looking annually at different ways we can change, different ways we can focus our efforts, different ways we can become more efficient,” he says.

Project Schoolhouse also changed grade configurations across the district. It moved sixth-graders to elementary schools in an effort to raise academic achievement and relocate seventh and eighth-graders to separate areas high school buildings, or kept them at middle school buildings, which were renamed junior highs, to better prepare them for high school. Hunt, who now serves as school board president, says the initiative will also strength neighborhood schools by closing facilities that were reliant on transfers.

“We have a lot of inequities among schools and we’re still working to improve those inequalities, but we're really implementing things that will make a difference, like all elementaries having an art teacher or a P.E. teacher or a music teacher,” he says. “There are definitely…’trade-ups’; that’s in the process ... and will take a few years to sort itself out.”

Lesson 5: “When you look back, you will have learned as much from adversity as you would have from good things.”

While the implementation of Project Schoolhouse has come with its share of challenges, some that are continuing, Ballard says he felt “lots of excitement and camaraderie” among the teachers when he met with them prior to the start of the current school year.

“I knew that implementation was going to be very difficult, and it has been, and we can find people today who say, ‘I supported Project Schoolhouse, but it’s been awfully hard. I don’t know how I feel about it now,’” Ballard says. “And I knew that would happen. I knew we would have difficulties and a couple of other things to iron out, but I will tell you, I believe with 100-percent certainty that it was the right thing to do.”

And Ballard continues in his pursuit of doing the right thing. He regularly solicits feedback from others in TPS, meeting with advisory groups of teachers, principals, and people in the community. He has also continued his dedication to the Teacher and Leader Effectiveness initiative, an evaluation model aimed at ensuring that there is an effective teacher in every classroom and an effective principal in every building.

“The new teacher evaluation model and everything we’re doing, to me, is the right direction for us to go,” Ballard says. “And I think people view TPS differently than they did three years ago.”

Funded, in part, by a grant from the Bill and Melissa Gates Foundation, the evaluation system is so well regarded that in early December it was selected as the state's new pilot program for evaluating teacher and administrator performance. On Dec. 15, the state Board of Education voted to allow school districts throughout Oklahoma to use one of three teacher evaluation systems during a one-year pilot period, according to the Tulsa World, with the Tulsa model potentially becoming the state system after that time.

Kevin Burr, associate superintendent for secondary schools, says the initiative could also affect how schools operate nationally.

In particular, House says, Ballard’s ability to work with the Tulsa Classroom Teachers Association to develop the evaluation method has attracted attention nationwide.

“To roll out an evaluation system that's so drastically different than what we had in the past would have raised so many eyebrows in a school system this large, but it's seamlessly been implemented with very little resistance,” he says.

As the spring 2012 semester begins, Ballard admits that his time at the helm of TPS is limited, but he plans to continue to focus on achieving goals, including seeing Project Schoolhouse fully implemented; creating a “vibrant and active” sixth grade that will have a long-term effect on improving the district's graduation rate; and ensuring that all students are reading well by the third grade.

Now, a second generation of the Ballard family serves in TPS leadership. Son Michael, an assistant principal at Will Rogers College High School, was a teacher and administrator in Claremore before coming to TPS in August 2011. He says his father supported his decision to move to the urban district and praised the people who work in TPS. And just as Ballard supported his son's childhood sports and school activities, he, continues to support him in his career.

“He always told me to do my best at whatever it is that I’m doing,” Michael says. “(He said to) be ethical and do what’s best for students. As far as me going into administration, he’d always say, you will want to put yourself where you can be in control and have an ability to make decisions.”

Keith Ballard, who was inducted into the Oklahoma Education Hall of Fame in August, says he plans to finish his career in the same place he began it — in the classroom — but he hopes that he has achieved he goal he set for himself four decades ago as an aspiring teacher: to make a difference.

“I didn’t do this for fame or fortune at all,” he says of accepting the TPS superintendent position. “I did this truly, at this point in my career ... because I wanted to be a part of the group that made a difference in Tulsa Public Schools. And if I can’t do that, then I don’t want to do this job. And there was a time early on where I wasn’t sure if we could make a difference. Now I know totally that we did make a difference.

“And there's more difference to be made. And my work won't be finished after I leave, but I hope that we will have built a system for the future that will serve the district well.”

More simply, Burr says, Ballard “righted the ship.”

“People have faith in this district," he says. “They believe that their kids are going to get a good education in Tulsa. And I think that belief was declining. That’s the ship he’s righting that he’s returned the faith in us, the faith in Tulsa Public Schools. In a lot of ways, that’s lifted all of Tulsa.”

Making the Grade

Keith Ballard's colleagues weigh in on what makes the Tulsa Public Schools superintendent an effective leader.

Susan Harris, senior vice president of education and workforce, Tulsa Metro Chamber: “Dr. Ballard has pushed through more positive change that will help students in the last three years than any Tulsa superintendent ever has before. The business community is especially appreciative of his support for a better data system to drive decisions, Teach for America, the new Teacher Leader Effectiveness program of evaluation and Project Schoolhouse. These changes will have a lasting impact on Tulsa students for years to come.”

Mike Neal, president and CEO, Tulsa Metro Chamber: “The fact that TPS was able to close or repurpose 14 buildings out of 89 without causing a community uprising is phenomenal. Dr. Ballard set up a remarkable system of community input and dialogue that resulted in closures that helped improve the programs and services for all children in the district.”

Lucky Lamons, president and CEO, The Foundation for Tulsa Schools: “He is an excellent communicator. He is able to convey what he wants to not only the Tulsa Public Schools administrators but to the Rotary Club, to the Sertoma Club. He is an excellent impromptu speaker. ... He truly cares about the education of children. There are some that can espouse that. It is deep in his fiber, the care and the importance he puts on education for children.”

Robyn Ewing, board chair, The Foundation for Tulsa Schools and senior vice president and chief administrative officer, Williams: “What Dr. Ballard does is he instills confidence in the community, in the board and in the employees of Tulsa Public Schools. ... (He) positively represents Tulsa Public Schools by being open and candid and trustworthy. I think he's seen as an individual who can present the unvarnished truth in an appropriate way. He's somebody who has dealt very ethically and honestly with all of the issues, whether it's the teacher evaluation system or Project Schoolhouse. I think that ethical part of Dr. Ballard really shines through.”

Christie Ballard, wife: “He has such a great sense of justice and wanting to do the right thing and wanting to help people who are maybe underprivileged and need help. And he really just enjoys being around people, talking to people....He truly is compassionate; he really cares about people. Because he came from a family that didn't have a lot of money, he really understands the importance of education and what a difference it can make in your life. It can change just everything.”

(0) comments

Welcome to the discussion.

Log In

Keep it Clean. Please avoid obscene, vulgar, lewd, racist or sexually-oriented language.

PLEASE TURN OFF YOUR CAPS LOCK.

Don't Threaten. Threats of harming another person will not be tolerated.

Be Truthful. Don't knowingly lie about anyone or anything.

Be Nice. No racism, sexism or any sort of -ism that is degrading to another person.

Be Proactive. Use the 'Report' link on each comment to let us know of abusive posts.

Share with Us. We'd love to hear eyewitness accounts, the history behind an article.