Last Tuesday, actor Eliza Dushku testified in front of the House Judiciary Committee during a hearing entitled "Silenced: How Forced Arbitration Keeps Victims of Sexual Violence and Sexual Harassment in the Shadows." It marked the first time Dushku has been able to speak freely about her experience on the set of the CBS show Bull in 2017. She detailed unrelenting harassment at the hands of series star Michael Weatherly, and enabled by showrunner Glenn Gordon Caron, after being cast as a series regular during filming of the show's first season.

"Off script, in front of about 100 crew members and cast members, he once said that he would take me to his 'rape' van and use lube and long phallic things on me and take me over his knee and spank me like a little girl," Dushku testified. In another incident, she recalled, Weatherly "shouted out that he and his buddy wanted to have a threesome with me and began mock penis jousting while the camera was still rolling. Then, as I walked off to my coffee break between scenes, a random male crew member sidled up to me at the food service table and whispered, 'I'm with Bull. I want to have a threesome with you too, Eliza.'" She said that only a day after privately approaching Weatherly to tone down the sexual comments, she was unceremoniously fired despite only receiving positive feedback from the network up until that point. Dushku's contract had the potential option for six seasons, but she ultimately appeared in only three episodes of the series. The show is now in its sixth season.

When Dushku decided to take legal action against CBS, she found that her employment contract included an arbitration clause—known variably as a "mandatory arbitration clause" or "forced arbitration clause"—a little-discussed provision that commonly appears in employment contracts across many industries. In effect, it preemptively strips employees, as a condition of employment, of the right to sue their employer in open court in the event that they suffer harassment, assault, or discrimination in the workplace. Instead, their complaints must be arbitrated in confidential, closed-door proceedings in which the employer chooses the arbitrator, often one it's used regularly. The process is thus stacked largely in favor of employers and corporations. A report by the American Association for Justice found that only 1.6 percent of arbitration cases in 2020 were decided in favor of the employee. Unlike cases tried in court, decisions are final and can't be appealed. The records are then sealed away.

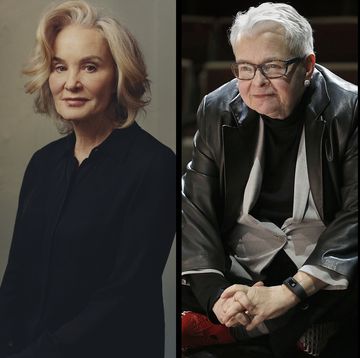

Dushku, who has been acting since she was 10 years old and has built a reputation for playing ass-kicking characters in shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, and Banshee was blindsided. With few options, she entered a settlement with CBS and signed a non-disclosure agreement as a condition of the settlement. When details of her case emerged in a 2018 report by The New York Times, she declined to comment, believing she was bound by the NDA. But after Weatherly, Caron, and CBS commented for the article, Dushku responded to their claims with an op-ed in The Boston Globe. And despite Tuesday's testimony, when the NDA could not be enforced, key aspects of her settlement—such as incidents of on-set harassment caught on tape that Dushku used as evidence in her case—remain locked away. "No one other than my legal advisers and CBS has ever seen or will ever see those tapes,” she said.

On Wednesday, the day after Dushku's testimony, the House Judiciary Committee voted in favor of the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Harassment Act. The bill is next slated for the House of Representatives. Dushku spoke exclusively to Harper's BAZAAR about her testimony, the professional repercussions and personal mental health toll of being bound by forced arbitration clauses, and why she can't imagine returning to Hollywood if it means signing away her rights.

You said that you'd approached your costar Michael Weatherly privately about his on-set behavior. The next day, you were fired. Your manager then had several futile conversations with showrunner Glenn Gordon Caron and CBS. At what point did legal action become the only way forward for you?

After the retaliation was so blatant. Here I am, somebody who's really established myself in this world, in my profession. That this could happen so overtly, and for there to be no repercussions, felt almost unbelievable. The irony of coming to be known for playing empowered female characters, and yet this could happen to me. But that's where I found myself and it felt very lonely and isolating.

You wrote in The Boston Globe that Caron told your manager, "If Eliza wants to be out of the business by suing CBS, she can go out of the business." Did that deter you?

It's a classic threat, a cliché of the kind of thing you'd hear in Hollywood. But I've been doing this for 30 years, and I never in a million years would have thought that I'd actually hear it. On the one hand, sure, it was intimidating and scary. But it was so egregious that it also emboldened me. After years of building myself up, I felt that of all people, I should be—I would be—the person to fight this. Because I couldn't imagine this happening to a 20-year-old me, new to this business, who didn't have the experience and stability that I have.

In your industry, you have a manager, an agent, lawyers who operate separately from your employer and help advocate on your behalf. Did that change anything?

I had a team that I really value, and I'm so lucky to have had that support. Still, I had to find my employment lawyer, who's based in Boston and has no ties to Hollywood. What quickly became clear was that even with the insulation and support that I thought I had, that mandatory binding arbitration clause that was buried in my contract basically took away all my options.

After all these years in the industry, was this the first time you'd heard of the mandatory arbitration clause?

I only learned about it after I contacted an employment lawyer. It was my employment attorney in Boston, not someone in my industry, who had to make it all really clear to me because it had never been discussed in my contract negotiations. Typically, we'll negotiate terms such as pay, travel, even trailers but this had never been something that I'd heard of. I asked people in the industry—managers, agents, people who are partners at the largest agencies and management firms—if they were aware that these binding arbitration clauses exist. Most of them said: "Absolutely not." And these are standard provisions that a lot of employers put in their employment contracts. The fact is that this doesn't just happen in my industry; it happens in many industries. That's one of the reasons I wanted to speak to you and to testify to Congress.

How did the employment attorney lay it out for you?

It came down to this: "Unfortunately, you've just told me about this awful experience you've had, but the fact that there's an arbitration clause in your contract means that you will not be allowed to have your day in court. When you signed your contract, you signed away your right to make a claim and have it fairly weighed in front of a judge or jury. Your only choice here is to go to a binding arbitration." And then they laid out all of the things that come with that. It was a pretty dark conversation.

After you learned about the forced arbitration clause, how did that change your options?

It made me realize how few options I had, and that what I had didn't seem like it would be a fair process. That it could be a two-to-three-year process. That it would be extraordinarily expensive. That I would have to sit with my harasser in a room and have a binding decision made by one person who would be a California arbitrator and who would likely be somebody that the studio has used time and time again. So they would have a home-field advantage, so to speak. That the process would also be completely secret and confidential, never to see the light of day. And then I came to learn that I wouldn't be able to appeal, that the decision is final. This was all just the opposite of what I thought we are trying to do as we progress in society—after the #MeToo movement, after exposing toxic cultures in the workplace, after fighting for more accountability. No matter what the outcome, there would be no public record of my case, and it would be as if it had never happened.

One of the ways mandatory arbitration clauses create a power imbalance between an employer and employee is that because the cases are kept private, there's no roadmap for people who come after you, no record. It seems like the process is deliberately created to make you feel alone. Was that your experience?

One hundred percent. Mandatory arbitration protects the harassers, the abusers, the corporations, and it isolates the victims.

I've since learned so much about the trauma and mental health effects of being silenced, of what happens when people do not have the ability to tell their stories. It encourages feelings of isolation and shame. In my case, I found myself asking, Why couldn't I stick up for myself better? And that really surprised me, given how tough I thought it was. I mean, I know I am tough today. But truthfully, it's taken a while for me to open back up and reclaim my voice. And that's such a fundamental part of who I am and who I felt I was. Mandatory arbitration takes away your voice. It creates a culture of silencing. It's a closed system, so there's no way to know about the hundreds or thousands of other victims. That makes others not want to come forward. It keeps others from reporting what's happened to them. It keeps others from seeking accountability.

You wrote in The Boston Globe that CBS used a personal Instagram photo of you wearing a swimsuit as part of their evidence during the settlement process. It's a regressive and offensive victim-blaming tactic. Do you think "confidential" arbitration and settlements allow employers to deploy particularly dirty tactics because they know it's not on the public record and they'll never be caught or called out for it?

Absolutely. They try to create a false impression that you brought this on yourself. They set out to create fear, intimidation, and shame. And so the process ends up revictimizing you. It was astonishing to find myself on the receiving end of the "how short was your skirt?" argument. Those photos were from social media, posted while I was promoting a film I had made about my father's mother country of Albania. I was wearing a bathing suit on the Albanian Riviera, celebrating this great, rewarding project. And to have that turned into "evidence" that implies I was asking to be sexually harassed was pretty eye-opening.

And in my case, my harassment was caught on tape—and it still didn't seem to mean anything. It would have meant something more, I think, if CBS had thought the tapes would go public, and that they would have to face scrutiny in a public forum, in an open court of law. So mandatory arbitration just empowers these huge corporation to behave even worse.

When CBS began an investigation into then-CEO Les Moonves and the company's corporate culture, details of your case began to leak. Places like The New York Times began to report on it. You didn't provide the Times with a comment but Weatherly and Caron did, which is why you responded with the op-ed for the Boston Globe. Was there any comfort in going public?

On one hand, of course, there is a very liberating aspect to it. I had been quiet for so long, and I felt guilt over that, and it affected me emotionally up to that point. I was allowed that response because of the leak.

On the other hand, I try to be careful here because, given the amount that the other side has broken our NDA and spoken out about my case in ways that they were not supposed to, you'd think that I would also be allowed to speak. But I truly don't feel that in my heart. And I still don't feel safe today. I don't want more controversy, I don't want more fear in my life. I have a three-month-old and a two-year-old, I'm newly married, I'm studying for my master's degree. But it just felt unfair, frankly, that my harasser and former employer broke the NDA to have the first bite of the apple, to shape the narrative that came out about the circumstances surrounding the settlement. They misrepresented things, they said things that were not true but were then repeated as if they were true by other people in the media. And then that was the story that was repeated.

How did you feel when you saw their comments to the Times?

I was devastated. I was angry. But if they were to speak publicly, and I wanted to respond, what does that look like? I would have to go back to my lawyer, then draft and send them a legal letter, and I'm back in a conflict with a Goliath corporation that has endless resources.

If you look at any of these other high-profile cases, there are these themes that repeat. There's the original incident, then there's often a denial, followed by a lot of gaslighting, and a lot of he-said-she-said, which is emotionally scarring. "No one believes me. How am I going to get people to believe me?" And then there's the retaliation, which is harder to fight when you're one person up against a corporation with more power and more resources to silence, discredit, and crush you.

The online coverage and the discussion of your case on social media often used terms like "secret settlement," which gives the misleading impression that you chose to enter a secretive process or that you had many other options.

I'll be honest, I had a hard time with settling. I was offered a settlement, and my only other option was to go through forced arbitration, which my lawyers warned was not likely to produce an outcome that was in any way fair or satisfying, even with the fact that I had proof on those recordings. But I accepted a settlement where I received part of my lost wages of the pay that I had signed a contract to receive over a six-year period. I ended up agreeing to receive only a little more than half of what that agreed-upon salary would have been. I also included other provisions that would protect other people in the future. I said that there needed to be an on-set sexual harassment compliance monitor. And I required that I would get the chance to meet with Steven Spielberg [an executive producer on Bull], who was a key figure in the Time's Up initiative at the time. And so those were the trade-offs that I made, which they initially resisted, but that I wouldn't budge on.

What power do you have to ensure that your provisions were actually honored?

Well, you know, it was in a signed contract. But there wasn't really a way for me to enforce what happened from there.

How did media coverage in the aftermath affect you?

The number of times that I've seen the term "allegedly" in the reporting of my harassment just makes my head spin. There was nothing alleged about it. It was all caught on tape. That kind of language does not make victims feel like they can speak out and get acknowledgment that something wrong happened to them.

And at the time, I was releasing a movie I had spent 15 years trying to make, that my brother and I produced, and it was really an important thing in my career and my art. When it came time for me to promote the movie, it coincided with details of my case leaking. I had magazine cover offers that were pulled because I wouldn't agree to talk about the things that I simply was not allowed to talk about. The night of the premiere, I was eight months pregnant and trying to do the press line, and reporters were still trying to get me to talk about it. And that was all a period where I felt like I had no option, really, other than to just stay silent. Because I had to make a choice. If they wouldn't interview me without me agreeing to talk about the leak, then I couldn't promote my work and do my job either.

Have you heard personally from other actors since your case became public? Is there a whisper network for this kind of thing?

Absolutely. And it's heartbreaking. A lot of messages of support I received were in private, in texts and emails, even from some people who are considered very powerful or empowered. Because even they are scared of their livelihoods being affected. A number of women—and men for that matter—asked me, "How did you do this? What should I do? Do you recommend I do something different? Did it feel better or worse after the fact? Have you been blacklisted?" Even just, "How are you? Alive?" I was grateful for their words. So I want to highlight for other people in this kind of situation that having strong peer support to offset the extreme isolation you feel is really important. Because, again, you feel so small and so alone when you're up against these corporations.

What's been the long-term personal and professional toll of forced arbitration for you?

You know, this is my livelihood, a career that I've devoted 30 years of my life to. My life has certainly gone on—I'm living my life in a way that is nurturing and empowering to me again, and I wasn't chased out of the business. But I will be honest, I haven't acted professionally since this happened. In many ways because my career used to make me feel empowered, but now, knowing what I know and experiencing what I experienced, I can't go back and continue in a system that requires me to sign away my rights. I would never sign away my rights again. And I realize the privilege that I have, in that I have been able to walk away and create another life for myself. I have family, I have support, and I have resources. There are people who don't.

I know it's a cliché, but you just don't think it's going to happen to you. And it did happen to me. And I can't find one person who can truly explain to me how forced arbitration is appropriate. It's unconscionable to ask people to sign away their rights in responding to sexual harassment before they even take a job. And it's just not how our laws should be designed. Our laws should be designed to protect people.

The old saying is: "We're only as sick as our secrets." To silence people, to silence women, to silence victims—these arbitration clauses are intended to do precisely that. And I just want to use my experience to educate your readers to educate my peers to educate as many people as possible. The reality is that this issue can affect anyone.

Last week, you were among a group of women to testify in front of the House Judiciary Committee as they considered the Ending Forced Arbitration of Sexual Assault and Harassment Act, which they later passed and will next go to the floor of the House of Representatives. How did it feel to hear the other women's stories?

I was just in awe of them the entire time, and just so devastated to hear what they'd gone through. I don't know them personally—yet—but I'm just so proud of them for having the kind of courage to stand up in such a public way. I was so amazed at their poise and grace and bravery. They gave vivid testimony—a real, human story.

How did it feel to share your experience in such a public forum?

I was nervous in the beginning. We've seen a lot of partisan shots fired back and forth, especially in recent years, so I didn't know what to expect. I suppose in some ways I was preparing for the worst. I was afraid for myself, and for these other women, that it would be revictimizing or retraumatizing. But I honestly felt like members of both sides were quite respectful and understood the magnitude of this issue and felt, with the exception of just a few, that most people are in favor of this bill. Because the status quo is just unconscionable.

At the end, Cori Bush asked everyone how we felt. And speaking for myself, I felt a sort of a lightness, like there was an elephant that stepped off my chest. I was proud to use my voice, to be able to possibly affect something so important. I feel a personal sense of closure for my experience because it's the silence that makes you sick, that erodes your sense of self, that erodes your self-respect and self-esteem.

What was your takeaway from all the testimony you heard and contributed to?

That forced arbitration kept these women's stories private, hidden from the rest of the public, so there was no accountability or transparency. And for others to know what these abusers and harassers have done, that's the only way this ends. With mandatory arbitration clauses, there's no accountability, no transparency. And so it continues. And that affects the culture both at specific workplaces and as a whole. If you keep harassment shrouded, that allows harassment to continue. We can heal from this, but the healing will come from action—from, hopefully, Congress choosing to act and protect future victims.

This interview was edited for length and clarity from two separate conversations.

Nojan Aminosharei is the Entertainment Director of Men’s Health and the Special Projects Editor of Harper’s Bazaar. He was previously the Entertainment Director of Hearst Digital Media, and before that a Senior Editor at GQ. Raised in Vancouver, Canada, Nojan graduated from NYU with a master’s degree in magazine journalism. The late Elaine Stritch once told him, “What the fuck kind of name is Nojan? I’m 89 years old, I don’t have time for that shit.”