Dave Gahan has always had his own voice, even when it seems shrouded in someone else’s vision. Angst, anger, the body and soul’s decay, the wrong emotions, the heart’s filthiest lessons—all are conveyed in Gahan’s voice with every deep, low breath. That the Depeche Mode frontman has chosen the medium of cover song for his newest solo album, Imposter, is as amusing and poignant as the recordings are striking. His takes on Mark Lanegan’s “Strange Religion,” Elmore James’ “I Held My Baby Last Night,” and PJ Harvey’s “The Desperate Kingdom of Love” sound as effortlessly provocative for Gahan as anything the Mode has captured.

Long a mouthpiece for Martin Gore’s words and music in Depeche Mode, Gahan began to put his own money where his own mouth was with 2003’s Paper Monsters and hasn’t slowed. Along with occasionally contributing tracks alongside Gore to Depeche products since that time, Gahan’s continued solo career has flourished, always with his aggressively dark decorum and deep baritone before the heatedly mixed music. As Depeche Mode prepares a black celebration for December’s remastered 101 live album and D. A. Pennebaker–directed documentary from their 1988 Rose Bowl set—expanded with rare songs and footage—Gahan unpacks the struggle he’s undergone to find his voice with Depeche Mode as well as on his own, and laughs often about what it means to stay an imposter.

Normally when people do solo albums they have something to say apart from their not-so-solo situation. How does a record of covers such as Imposter work? It feels more celebratory than the work you’ve written alone or with Soulsavers.

It’s definitely a continuation of the two albums that came before this, of the collaborative relationship with Rich Machin and all of the collective musicians that become Soulsavers. Rich and I got to this point where we have chemistry in terms of writing. The chemistry is still there on Imposter, even though we’re not writing. That chemistry is definitely there with the musicians in the studio. The choice of songs became, in a weird way, the narrative you’d look for in a body of work you had written.

“There’s a deep identification that I feel for the songs of Imposter. As a singer, I have to say that I don’t know that I’ve ever felt more comfortable with any collection of songs as I did this lot.”

So its curation became the anecdotal throughline.

Perhaps because I’d known these songs for many, many years—listened to and loved these songs, or felt something for the singers themselves—this music spoke to me. Really spoke to me. There’s a deep identification that I feel for the songs of Imposter. And I don’t know that I was particularly aware of all that when I was choosing the songs with Rich. That realization just kind of happened after we’d recorded the first five songs. I suddenly felt very comfortable. It came together very easily. As a singer, I have to say that I don’t know that I’ve ever felt more comfortable with any collection of songs as I did this lot.

Was the narrative thread fully discovered by the time the recording process started?

Yes, but that’s just for me. That was my point of view, something that I hadn’t discussed with Rich. After we finished recording and were on our way to mix in London, I had the sequencing laid out, and had the idea to call it Imposter…

A genuinely clever name for a covers album, too.

Thanks. I did mean for it to be tongue-in-cheek. But it’s ironic as these songs didn’t feel like that at all.

You didn’t feel like a pretender singing the words of Dylan or Neil Young.

The vibe of all of us in the studio, that comfort level that we achieved, made it all feel as if I was singing my own songs. It must sound odd to hear that, but it all just felt natural.

“So the challenge has become—and always is—how can I make this song feel like my own? Be genuinely coming from me? If that’s not believable for me, then you’re not going to believe it either.”

By this point, yours and Rich’s relationship is over 10 years old. How would you best describe the evolution of your involvement?

Rich and I have become friends, so there’s that relationship. When I was making the last Depeche Mode record, Spirit, Rich and I spoke a lot. There was some friction there between Martin and myself over choices of songs, the usual friction that comes from me trying to push my way in there with a few songs of my own. It’s healthy, that friction—a good thing for Depeche. When there are two songwriters in one room, sometimes you both fight for space.

You wanted a deeper part of that creative process.

Yes. It was something I had to do. And Rich, over the years, has been very supportive of me in that department. It got pretty sticky there for a moment with Martin. During the making of Spirit I wasn’t sure if I wanted to continue working in an environment that felt kind of hostile to my ideas. I couldn’t understand why Martin wouldn’t want to bring the best out of me, as I’ve felt that I brought the best out of him and his ideas over the years.

And Imposter, a collection of other people’s songs, is similar to what you do with Martin.

Oh, yes, exactly. I’ve been doing this for years, singing someone else’s songs. So the challenge has become—and always is—how can I make this song feel like my own? Be genuinely coming from me? If that’s not believable for me, then you’re not going to believe it either. I had a long apprenticeship to get where I am with Imposter.

“If you’re not willing to go down the dark end of the street and come out the other side, I’m not interested in portraying it.”

We’ve talked in the past, and you’ve let me know how much you wanted to be represented in Depeche Mode, that you wanted your songs to be sung.

Some of them, at least [laughs]. Depeche Mode is the place where Martin’s songs get recorded. There had to be a limit on the amount of songs I could contribute—if there were 12 songs on an album, I’d get four, if there were 10 songs on an album, I’d get three. Once that was made clear, the air was cleaner between us. There’s so much time spent making a Depeche Mode record, and so much of that time is often wasted, baffing around with all the equipment. Let’s just record as many songs as we can. With that, I’ve been able to record my ideas outside of Depeche Mode, and I’ve made time for myself for a bit more exploration.

You covered Mark Lanegan’s song “Strange Religion” on the album, a love song driven by the metaphor of spirituality, the question of what is and isn’t holy. How do you express your spirituality?

For me, growing up, religion was terrifying. Singing in church, though, actually made me feel as if I belonged to something. I really enjoyed that. Moving from there, and trying to find love—or hide from it— they’re all so close, yet far away from us, sometimes. “Strange Religion,” for me, metaphorically also describes that relationship with another person, maybe the last person in the world who would reveal something to you about the position you find yourself in. I hear someone that I clearly identify with in Mark’s voice.

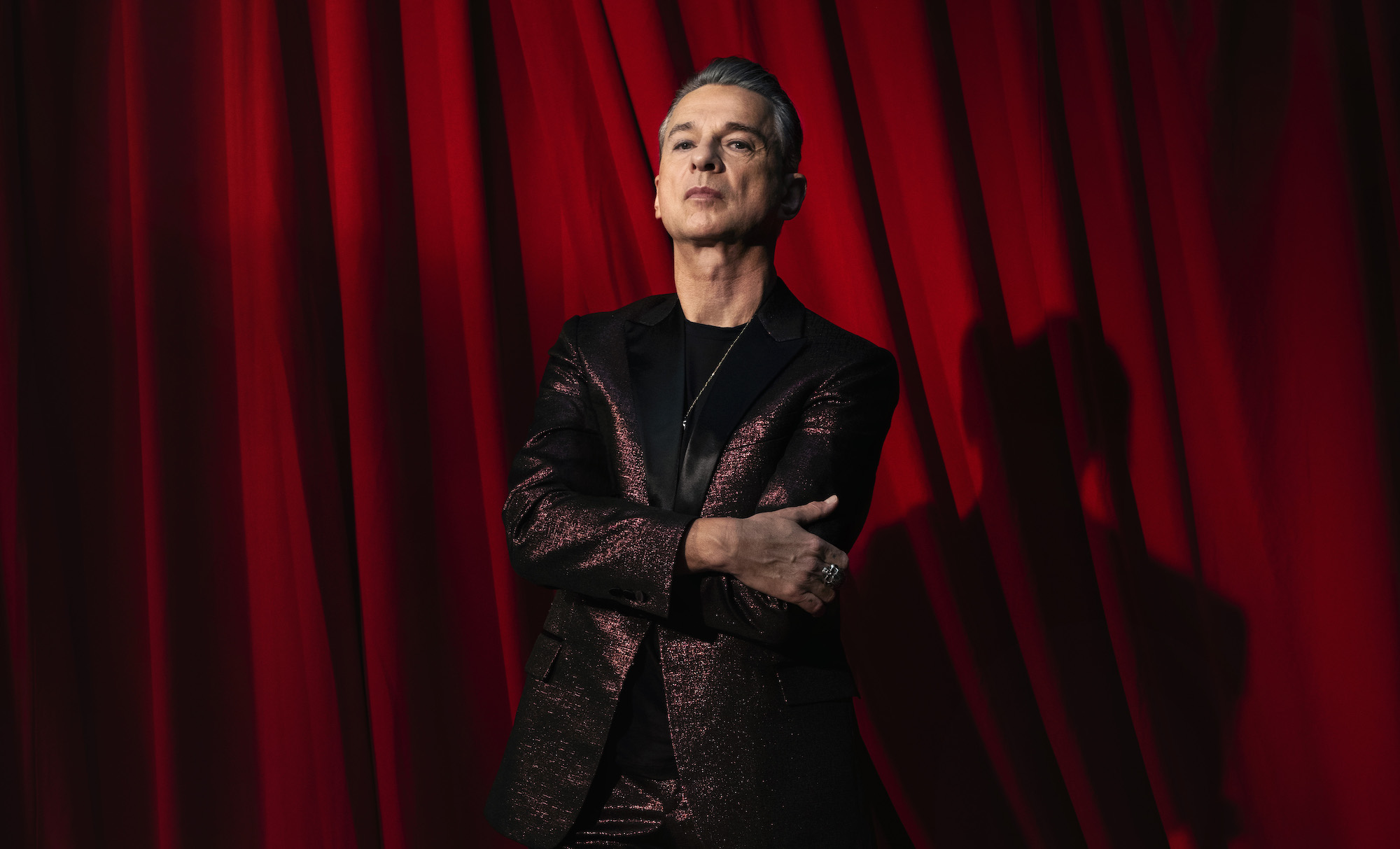

photo by Sean Matsuyama

Can you connect the dots between you and the Charlie Chaplin standard “Smile”?

This also goes back to my childhood. I was enamored by him. He was the ultimate imposter, having created this character who made us laugh and cry. I could identify with him being a sad clown with a dark presence. Plus, I think the song is one of the best ever written—there’s real space and simplicity that allows the listener to create their own narrative. My one stipulation was to keep the arrangement as minimal as possible, and I did it in one take. All of the songs on Imposter wound up being just like that, but this one being so bare, I wanted to hit it in one performance. By the end of that song, I’m either laughing or crying, or a bit of both at the same time. When I was done with that in the studio, I had to go for a walk. I felt as if I had no clothes on.

You also capture Elmore James, Neil Young, Gene Clark, and Bob Dylan—all songs that hew closely to the American folk idiom. They’re very rural, and specific to time and place. How does that moment speak to you?

For me, if the voice can take on a cinematic quality, or make something visual, I’m very drawn to it. The singers I’ve chosen here have affected me greatly. They do something that turns me on my head, makes me feel something. There’s always more to be revealed—that’s what’s always more exciting. If you’re not willing to go down the dark end of the street and come out the other side, if you’re lucky, I’m not interested in portraying it. That’s how I navigate my life. I used to have this problem with being “just the singer.” But I’ve come to realize that I’m a pretty good singer [laughs], and that these songs pushed me into places where I want to go. Or don’t want to go. FL