A National and Local Reflection on the History of Indigenous Peoples’ Day

President Joe Biden announced through a presidential proclamation that Oct. 11, the second Monday of the month, would mark the Indigenous Peoples’ Day, making him the first American President to recognize the holiday. This holiday has been celebrated for decades, with many states and cities in the past decade declaring it a holiday in their jurisdiction.

These declarations came mostly, but not exclusively, in protest of Columbus Day, which is recognized as a federal holiday by Congress and falls on the same date as Indigenous Peoples’ Day. Columbus Day has faced much scrutiny due to the Italian explorer’s inhumane and vile treatment of Native Americans after his first landing in the western hemisphere.

Dickinson College has a unique story in relation to Native American history, especially with the Carlisle Indian Industrial School (CIIS). Not only did the CIIS leave a dark stain within the area, its influence spread across the continent, and its ability to prosper came in part because of Dickinson College.

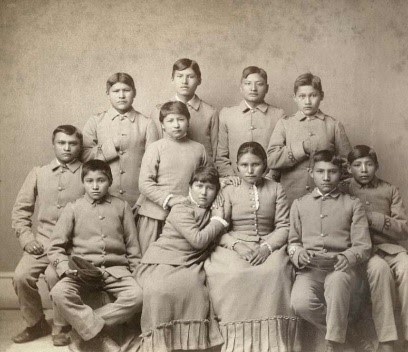

After the Red River War, Richard Henry Pratt, who was in charge of overseeing roughly 70 Native American prisoners of war at Fort Marion in Florida, began an experiment to assimilate them into English speaking American culture. He founded the Carlisle Indian Industrial School afterwards in 1879, at the petition of Carlisle and Dickinson College locals.

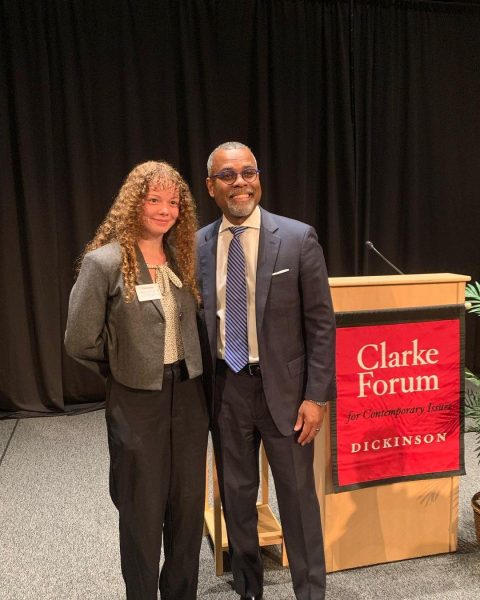

After the school was founded, it became a part of federal regulations that poor Native parents would send their children to one of these Indian boarding schools, with Carlisle being the most influential. Students were stripped of their own culture by being forced to shave their heads and pick a new English name, among others. Once the school was in motion, there was a large push from Dickinson College to keep the school going. Darren Lone Fight, an assistant professor of American Studies at Dickinson, said that the link between the two institutions was “intimate,” with the College honoring Pratt with an honorary PhD, as well as his successor as superintendent, Moses Friedman. Other examples are Dickinson’s President at the time giving the first sermon at the CIIS, college faculty working there, and several college presidents helping the school expand its territory to be able to support a larger student body. Professor Lone Fight described Dickinson by saying “there is no other college on the planet that has a closer relationship to the Indian boarding school system.”

The success of the CIIS led to the widespread implementation of Indian boarding schools across the United States and Canada, even after its closing in 1918. These boarding schools would be open across the continent until the 1960’s. Recently, outcries have come due to unmarked graves of hundreds of children who attended these schools being found, with the Canadian government taking acts to mourn and disavow the forced assimilation that these schools caused. In reaction to this, the sites of many of these old schools in both countries have made steps to return the remains to the tribes they were a part of. In the summer of 2021, Deb Haaland, Secretary of the Interior and the first Native American to head the department that oversees Indigenous affairs, visited Carlisle to announce the United States’ work to identify its dark history with the boarding schools. This visit came with the Rosebud Sioux tribe exhuming nine of their own children, and a wish from Sec. Haaland that the children who were never allowed to return home be named, allowing a form of healing for herself and the tribes who lost their children in a dark part of American history.

An important question to ask ourselves as a college community is “What can be done to reverse the damage that was done by generations before us that still impact our society today?”. Many schools would simply celebrate local Native American tribes and cultures for Indigenous Peoples’ Day, but Dickinson College can also take the responsibility to, as Professor Lone Fight says, “do more than celebrate… [and] to materially support and undo the damage they facilitated for a very, very large group of indigenous sovereign nations.” Not only is there the CIIS, but Dickinson was also founded on the land of the Susquehannock people. Both of these issues were at the forefront of Dickinson’s Land Acknowledgement, written by Professor Lone Fight, which is a step in the work to acknowledge the complex history of Dickinson College. These issues in the school’s history are summarized in one quote from the Land Acknowledgement, “This relationship [with the Carlisle Indian Industrial School] represents our failure to have recognized in these peoples and their nations different but no less self-sovereign ways of thinking, living, and being. We recognize and take responsibility for the college’s support for this attempted eradication of Indigenous peoples—a profound moral failing in stark opposition to our mission today.” There are other ways that, as a student body, we can acknowledge our school’s history, such as taking the time to learn more about these complex issues and the impacts they have left behind on many unique indigenous cultures. We as a college can also find ways to take the harm brought about the CIIS and use it to undo the wrongs it brought about such as a possible degree, minor or major, in Native American Studies, or events to highlight the history of indigenous people in this area. No matter what happens in the future, much like the rest of American society, Carlisle and Dickinson College has done a lot to right the wrongs of our ancestors towards indigenous peoples, but we still have some much more to be done.