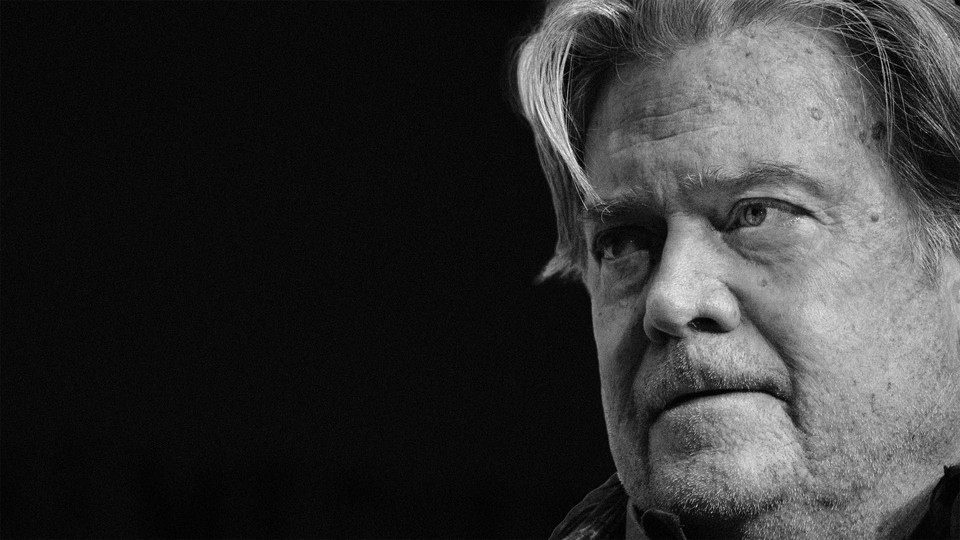

Steve Bannon Knows Exactly What He’s Doing

The fight over January 6 is about much more than the law.

Updated on Monday, November 15, 2021 at 4:03 p.m. ET

Does anyone still remember the Chicago Seven?

They were a disparate group of radicals—some who knew each other, some who didn’t—who went to the Democratic convention in Chicago in 1968 to spark trouble. Trouble did indeed erupt, although maybe not the exact trouble they had wanted. They were indicted and prosecuted. And then things went terribly wrong for the government.

The prosecution thought it was running a trial, a legal proceeding governed by rules. The defendants decided that they would instead mount a new kind of media spectacle intended to show total contempt for the rules, and to propagandize the viewing public into sharing their contempt. The prosecution was doing law; the defense countered with politics.

The indictment of Steve Bannon for contempt of Congress is the opening bell of a similar kind of fight over law, justice, and authority. The attack of January 6, 2021, to stop the lawful transfer of presidential power struck nearer the heart of American democracy than the disorder in the streets of Chicago had. In 1968, the worst of the violence was mostly initiated by police; in 2021, it was initiated by the pro–Donald Trump mob forcing a police officer to shoot to defend the officeholders whom it was his duty to protect. But though the details of the riots were different, there is a striking parallel between the gleeful contempt for legal authority of the far-left defendants of long ago and the pro-Trump authoritarian nationalists of today. Congress wants to hear from pro-Trump partisans about their advance knowledge, if any, of the January 6 attempt to halt the certification of the 2020 presidential election. At former President Trump’s direction, those partisans have adopted a no-cooperation strategy, pleading that the defeated ex-president should permanently enjoy the legal privileges of his former office.

That’s not a very smart legal strategy. But it’s not meant as a legal strategy. It’s a political strategy, intended, like the Chicago Seven’s strategy in Judge Julius Hoffman’s courtroom all those years ago, to discredit a legal and constitutional system that the pro-Trump partisans despise.

The Trump partisans start with huge advantages that the Chicago Seven lacked: They have a large and growing segment of the voting public in their corner, and they are backed by this country’s most powerful media institutions, including the para-media of Facebook and other social platforms. “I want you guys to stay focused, stay on message,” Bannon told supporters on Monday, after turning himself in at the FBI’s Washington Field Office. “Remember, signal not noise.”

Thanks to their messaging advantage, Trump partisans don’t need to convince much of anybody of much of anything. It won’t bother the Trump partisans that their excuses are a mess of contradictions. They say that nothing happened, and that it was totally justified; that Trump did nothing, and that Trump was totally entitled to do it. Their argument doesn’t have to make sense, because their constituency doesn’t care about it making sense. Their constituency cares about being given permission to disregard and despise the legal rules that once bound U.S. society. That’s the game, and that’s how Bannon & Co. will play the game.

Permission seeking and permission granting were exactly how January 6 happened in the first place. Trump supporters were gradually radicalized through a series of escalating claims:

Trump didn’t really lose.

The majority in a state legislature has the right to reverse that state’s election results if it does not agree with them.

The vice president can initiate that reversal process if he wants to.

If the vice president balks, kidnapping him and putting a gun to his head until he changes his mind is legitimate.

If the plot fails, any attempt to hold the would-be kidnappers to account is unjust political persecution.

Now, in 2021–22, the project is to repeat that kind of kaleidoscopic shift of denial and justification. Like the Chicago Seven, Bannon understands the political power of ridicule and contempt. He’s not coming to trial to play by somebody else’s rules. If he does eventually testify about the events of January 6, he won’t play by the rules then, either.

Bannon and Trump’s strategy of distraction and denial won’t necessarily succeed. Most people recognize reality. But to prevent the strategy from working, it’s important to anticipate it and be ready for it.

The most important basis of national self-defense is to always keep in mind the limits of criminal prosecution to deal with political wrongdoing. Many things are wrong without being illegal—and certainly without being provably criminal. The criminal law rightly demands overwhelming evidence. Convicting people unable to recognize they were doing wrong can be very difficult.

The Robert Mueller investigation into Russia’s intervention in the 2016 election should’ve made particularly clear the inadequacy of the criminal process in a political context. The country needed to know from Mueller whether Donald Trump—as a businessman, candidate for office, and president—had improper connections to Vladimir Putin’s Russia. Mueller instead went looking for proof of a criminal conspiracy within the technical legal definition. But a businessman hoping for a giant payday from shady characters around a foreign dictator is not a prosecutable crime. A businessman lying on camera about his dealings with the shady characters around a foreign dictator is not a prosecutable crime. Being tipped off that the foreign dictator has potentially damaging information about a political opponent is not a prosecutable crime. Appealing on television to that dictator to hurry up and release that information is not a prosecutable crime. Once the statute of limitations has lapsed, even money laundering ceases to be a prosecutable crime.

Through all the long months of the Mueller investigation, people who followed the Trump-Russia story were led to hope that the thing would end with Trump doing a perp walk. Excited anti-Trump media sometimes inflated Americans’ expectations about what federal prosecutors could or would do. They sometimes overhyped rumors into reports. In doing so, they redirected attention from the need for coalition-building and vote-winning to a messianic hope: “Mueller is coming.” Only Mueller was not coming, because Mueller and the Trump Department of Justice had defined his job in a way that forbade him from looking at the stuff that mattered most: intelligence risks rather than criminal charges, and the financial transactions that cast light on the story, even if they did not break the law.

Here we are again. Trump’s consigliere Michael Cohen testified a long time ago that Trump does not leave a paper trail. He does not speak direct orders. He signals what he wants, and then leaves it to his underlings to figure out for themselves how to please him. Trump likely followed those lifetime habits in the weeks leading to January 6.

The struggle between supporters of constitutionality and legality, on the one side, and Trump and his faction, on the other, is always an asymmetrical fight, as it was between the law and the Chicago Seven in 1968. Those trying to protect Trump from accountability for January 6 know what they are trying to accomplish and have built a large constituency in the country that supports them. The fight to uphold law cannot be won by law itself, because the value of law in the face of violence is the very thing that’s being contested. The fight ahead is an inescapably political fight, to be won by whichever side can assemble the larger and more mobilized coalition. The Trump side is very clear-eyed about that truth. The defenders of U.S. legality and democracy against Trump need to be equally aware.