Rocky Marciano beating Joe Louis a true case of passing the torch

In boxing, it is often said that to be The Man you have to beat The Man, but that is not always the case. In some instances, it is demonstrably false. For purposes of tracking the true lineage of the heavyweight championship of the world, early 20th century ruler Jack Johnson stands as an example of someone who unquestionably was The Man; his loss to Jess Willard under a hot Cuban sun, still the source of much speculation, did not fully legitimize Willard, at least not on the level of the fighter he had just supplanted. But the snarling beast who dethroned Willard, Jack Dempsey, soon revealed himself to be The Man as much as had that other Jack.

And so has it always been. There are other universally recognized heavyweight champions who have taken their places in the pantheon where only the best of the best reside, but there are yawning gaps in the chain, especially in the era of multiple alphabetized title-holders. Leon Spinks might have usurped Muhammad Ali to briefly end one of “The Greatest’s” reigns, but that massive upset did not – could not – put Neon Leon alongside Ali for the purpose of historical posterity.

Technically speaking, Rocky Marciano’s eighth-round knockout of an aging Joe Louis on Oct. 26, 1951, did not signify a passing of the championship baton. The 37-year-old Louis, the legendary “Brown Bomber” who occupied the throne for a record 12 years and 25 successful defenses, had retired in 1949, the crown he vacated having been won by Ezzard Charles and then lifted from Charles by Jersey Joe Walcott. Marciano, 28, wasn’t nearly as polished as the Louis who was still wore a certain aura of greatness despite not being in his glorious prime, but the “Brockton Blockbuster” was a devastating puncher and increasingly viewed as someone whose power could make up for any technical deficiencies.

Seventy years have passed since Louis and Marciano squared off in Madison Square Garden, and the fact that a bejeweled belt was not on the line scarcely seems to matter now. Such changing-of-the-guard bouts stand as stark testimony that an era has expired and must give way to another, the same in the ring as it is in nature, where an old and proud lion eventually must yield as head of the pride to a younger, stronger version. Ironically, the same scenario had played out during the recently ended baseball season, also in New York City, with a Louis equivalent, Joe DiMaggio, playing out the string in center field for the Yankees while his designated replacement and Marciano stand-in, rookie Mickey Mantle, was temporarily stationed in right field.

Larry Holmes battered a faded Ali in 1980. Photo from The Ring Archive/ Getty Images

Some have suggested that Marciano-Louis was a precursor of sorts to Ali’s doomed-to-failure challenge of WBC champ Larry Holmes, his onetime sparring partner, on Oct. 2, 1980, but the analogy is flawed. The comparison makes sense in certain ways, but the reality at that time was that Ali was a 38-year-old shell of his former brilliance and Holmes, 30, already was the best heavyweight in the world and making the eighth defense of the title he had won on a rousing split decision over Ken Norton 2½ years earlier. Only the most deluded Ali partisans could have believed their faded idol had any chance of upsetting Holmes, who grudgingly administered the beatdown that everyone should have realized was inevitable.

Even in Louis’ pugilistic dotage, however, there were more than a few of his backers who helped send him off as a 7-5 wagering choice over Marciano, and not solely for sentimental reasons. At 6-foot-2 and a career-high 213¾ pounds, Louis was 3½ inches taller and 29¾ pounds heavier than his squatty opponent, a physical prototype of future champs Joe Frazier and Mike Tyson. Perhaps even more significantly, Louis had a stupendous advantage in reach,76 inches to 67. And if all that weren’t enough, several important media observers were continuing to deride Rocky as a clumsy oaf with two left feet who had outlasted lesser foes, but was apt to receive a boxing lesson from the still-capable master.

Ed Fitzgerald, one of the leading sports writers of the era, was among those who didn’t believe 10 scheduled rounds constituted enough time for Marciano to track down and take out so experienced and tactically proficient a fighter as Louis. Still, Fitzgerald expressed admiration not only for Marciano’s vaunted overhand right, which Rocky had dubbed the “Suzie Q,” but for his willingness to absorb copious amounts of punishment in exchange for any chance he had to dish out some of his own.

“Rocky is not in there to outpoint anybody with an exhibition of boxing skill,” Fitzgerald wrote. “He is a primitive fighter who stalks his prey until he can belt him out with the frightening right-hand crusher. He is one of the easiest fighters in the ring to hit. You can, as with an enraged grizzly bear, slow him down and make him shake his head if you hit him hard enough to wound him, but you can’t make him back up. Slowly, relentlessly, he moves in on you. Sooner or later, he clubs you down.”

Marciano would establish himself as one of the greatest heavyweight champions of all time. Photo courtesy of Bettmann

The career intersection of two remarkable and Hall of Fame-worthy careers, one already firmly established and the other in the process of being so, attracted a full house of 17,241 that generated a gross of $152,845, major bucks for that time. And why shouldn’t a fight such as this have sold out the arena? Marciano came in at 37-0, with 32 knockouts, while Louis, fighting for the eighth time in 1951 on the comeback trail (all seven previous bouts were victories), was 66-2 (52). Either the young lion would roar in exultation, or the old king of the jungle would again demonstrate that he was not quite ready to step aside.

It was soon evident, however, that this was not the same Brown Bomber who had likely established himself as the greatest of all heavyweights up to that point. His hair was thinning and, 13 to 15 pounds over his optimal fighting weight, he was a bit thicker around the middle. Even so, he won a couple of early rounds on guile and muscle memory, but, as Fitzgerald had noted, Marciano slowly, relentlessly moved in on him in expectation of clubbing down a fighter whom he had come up worshiping.

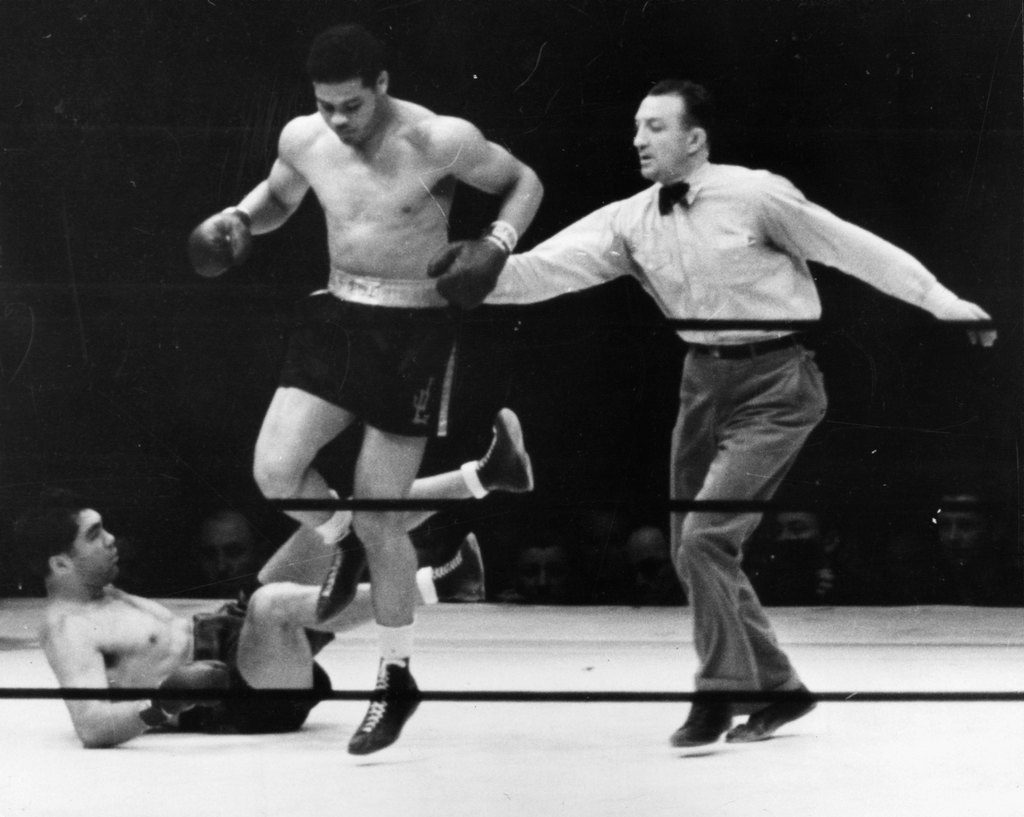

The end came, as it surely had to, in the eighth round when Marciano registered two knockdowns. The first merely had the effect of hurting Louis, but the second finished him not only for that night, but for keeps. It was, natch, the “Suzie Q” that provided the exclamation point, which sent Louis crashing through the ring ropes where he lay on his back on the ring apron, semi-conscious and unable to rise.

Referee Ruby Goldstein, who had toured World War II Army bases with Louis, had no hesitancy in saying that Joe was his friend, an admission that in another time might have prevented him from getting that assignment as third man in the ring. Goldstein’s reputation as a conspicuously diligent arbiter presumably put him above any suggestions of partisanship, but it nonetheless pained him to see Louis – who never fought again – go out that way.

“For many people it was a sad affair,” Goldstein allowed. “A great sports figure like Lou Gehrig or Babe Ruth is finished. People idolized Louis. They didn’t want to see him when he was not himself. It wasn’t easy for me. We were friends. But when you’re a referee, you’ve got to steel yourself. You’ve got to realize there are two boys in the ring, and they are trying very hard to win the fight.”

Nor was Goldstein the only involved party who had ambivalent feelings about the way Louis was ushered out of the sport which he once bestrode like the Colossus of Rhodes. Marciano was hesitant to even accept a bout against someone he so admired, but his manager, Al Weill, convinced him that the most direct route to the heavyweight title was through Louis. To make a fight upon which so much presumably hinged, a confident Weill even consented to a contract that guaranteed Louis 45% of the gross receipts and only 15% to Rocky.

“I feel sorry for Joe,” said Marciano, whose reaction to the most important triumph of his career must have seemed strangely muted. “I’m glad I won, but I feel sorry.”

For his part, Louis felt he had nothing to complain about. He had his run, and it was long and terrific, but for every fighter there comes a time when reality, in the form of Father Time as much as any particular opponent, slaps you upside the head.

“This kid knocked me out with what, two punches?” Louis said in his dressing room. “Two punches. (Max) Schmeling knocked me out with must have been a hundred punches. But I was 22 years old then. You can take more then than later on.”

Perhaps the fiercest and least yielding protector of the Louis legend was Arthur Daley of The New York Times, who opined that “the Louis of 10 years ago would have felled Rocky with one punch. Louis losing is more important than Rocky winning.”

A prime Louis (seen here during his destruction of Max Schmeling) against Marciano would have been a fight for the ages. Photo from The Ring Archive/ Getty Images

That tepid take on what had happened on a cool Bronx evening in October was countered by this, from Seattle-area boxing promoter Jack Hurley, who ventured that although Marciano was “not another Dempsey, he will take the place of Dempsey and bring boxing back to where they’ll want fighters, not just fancy Dan boxers. He’ll be trying for the knockout from the opening bell, tough and strong and trying to knock your brains out every minute, the kind of champ the American people love.”

All that remained was for the rest of the story, the parts that extended beyond the competitive arena, to play out for both Joe and Rocky. Louis lost big-time on points to the Internal Revenue Service, which seized most if not all of what remained of his boxing earnings, and he spent his later years as a greeter at Las Vegas’ Caesars Palace. Marciano won four more non-title bouts, all by kayo, before wresting the championship from Walcott on a 13th-round knockout on Sept. 23, 1952. Not surprisingly, The Rock trailed on the scorecards before he again connected with the Suzie Q. He defended the championship six times before announcing his retirement, at 32, on April 27, 1956.

Fat and seemingly content in retirement, Marciano, then 44, dropped hints that me might be interested in coming out of retirement after Sweden’s Ingemar Johansson floored Floyd Patterson, who had won the title Rocky had vacated, seven times en route to a third-round stoppage on June 26, 1959. Marciano believed that, given enough time to whip himself back into fighting shape, the Suzie Q would be enough for him to do unto Ingo what Ingo had done to Patterson. New York sports columnist Jimmy Cannon was dismissive of that notion, writing that Marciano was foolish to “consider another fight as he struggles to free himself from the bondage of obesity.”

But before Marciano could act, or not, on his plan for a boxing return he perished on Aug. 31, 1969, the day before his 46th birthday, in the crash of a small private plane in an Iowa cornfield. Since his retirement he had won over new generations of fans through frequent viewings of his fights on YouTube and ESPN Classic. Like Louis, he appears regularly in the top 10 of many so-called experts’ lists of the 10 greatest heavyweights of all time.

READ THE MARCH ISSUE OF THE RING FOR FREE VIA THE NEW APP NOW. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO ACCESS MORE THAN 10 YEARS OF BACK ISSUES.