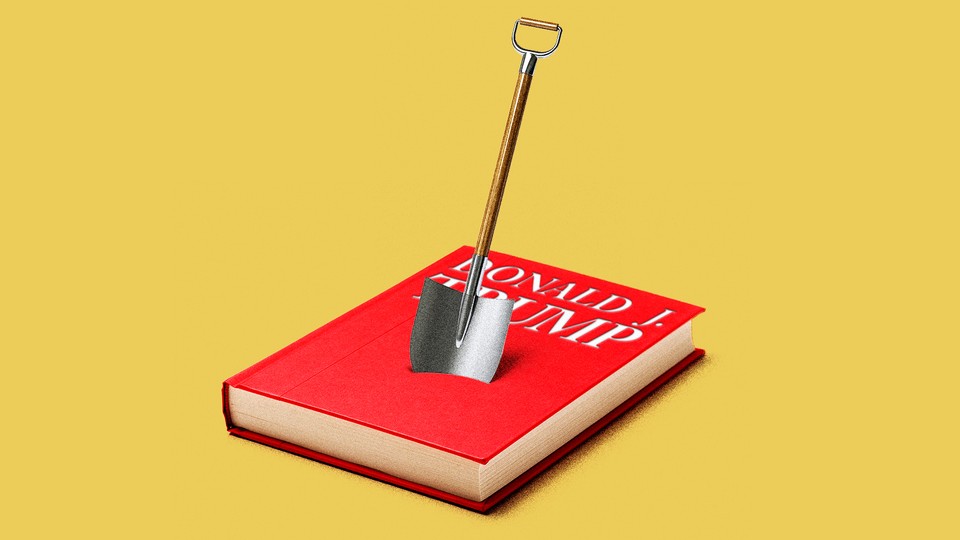

William Blake once proposed that John Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it” because he evoked Satan in Paradise Lost with such gusto. By contrast, Blake observed, Milton seemed inhibited when he wrote of plodding, sanctimonious old God. Have Donald Trump’s recent chroniclers, most of whom quote the former president liberally and with relish, turned to the devil’s party?

Loathsome characters bring out zestful writing, and authors who represent Trump as perilous to democracy—that is, all writers with eyes and ears—could find that the danger the former president poses to America’s future is more cinematic than democracy itself.

Peril, the latest big book about the former president, is not the best book by Bob Woodward, or even his best about Trump. That would be Fear, which came out in 2018. But in Peril, Woodward and his co-author, Robert Costa, manage to pull off a singular trick. They don’t let Trump’s devilish ravings, tweets, and tantrums run roughshod over their own, more disciplined voices. Woodward and Costa flex their rhetorical muscles not by writing the hell out of the Trump character, but by smacking down their arch-villain, keeping a choke chain on his every utterance.

When writing about the appalling presidential debate of September 30, 2020, they skip Trump’s cruel and confounding yawps about Joe Biden and Biden’s son, Hunter. They also ignore the Proud Boys, whom Trump that night refused to condemn. Given that group’s participation in the attacks of January 6, Trump’s words—“stand back and stand by”—now seem stomach-churning and fateful. But in Peril, the sole line Woodward and Costa quote from that debate is Biden’s demand of Trump: “Will you shut up, man?” With this choice to not quote Trump at all, the book elegantly obliges Biden.

For years, Woodward has been accused of styling himself as “impartial” during a crisis that demands partiality. But this underestimates the old master’s ego. Woodward takes a side: his own. His voice in Peril is imperious, swaggering, and territorial. He and Costa lock their subject in a narrative cage, where he remains mostly gagged.

Other recent Trump books allow their subject more space to strut and fret. This has costs, but it also means they bring more brio to evoking the former president. These books are potboilers: Stephanie Grisham’s I’ll Take Your Questions Now, Michael C. Bender’s “Frankly, We Did Win This Election,” Carol Leonnig and Philip Rucker’s I Alone Can Fix It, and Michael Wolff’s Landslide. These Trump books align in that they keep the former president’s flamboyant psychopathy center stage, where readers can hate-watch it. They all read like airport thrillers.

But the books also play back Trump’s falsehoods, sometimes at top volume. Three draw their title from lies told by Trump, and two directly quote the so-called Big Lie. Trump didn’t win the 2020 election—neither “frankly” nor by a “landslide”—and he alone could not fix jack. But it’s not just the titles that replay Trump’s lies. At regular intervals, Grisham, Bender, Leonnig and Rucker, and Wolff quote or cite Trump’s horseshit, often letting it steam there, uncorrected.

This can have unnerving effects. About midway through Landslide, Wolff writes of “the president’s determination to sully Joe Biden,” a motivation for defamation and lies if ever there was one. (See: Trump’s first impeachment.) But hot on the heels of this statement, Wolff asserts that Trump has “absolute belief that the Bidens were among the most corrupt political families of all time.”

Does he? An absolute belief? Wolff doesn’t mention that this is a ludicrous claim, and with Trump hardly anything is “absolute” or a “belief.” But to note any of this would break Wolff’s narrative flow; his talent is for free indirect discourse, which lets him enter the minds of his principals, and he’s never going to clutter his slick prose with allegedlys or weasel words chosen by lawyers. So rather than punish the character of Trump, as Woodward does, Wolff lets Trump run wild. In all of his books, including a new one out this month about, no joke, “the damned,” Wolff is inexorably drawn to the devil. (Unlike Milton, he always knows it.)

Another example of the difficulty of rendering Trump’s freaky deceptions comes in a chapter about his 2020 electoral defeat in I Alone Can Fix It. In describing Trump’s rejection of data, Leonnig and Rucker write, “Georgia was MAGA territory—or so Trump thought.” Georgia in 2020 was very much not MAGA territory. Biden beat Trump statewide to win the state’s 15 electoral votes, and both of its Senate seats flipped to Democrats. But the fact that Trump’s stubborn delusion—“Georgia was MAGA territory”—is allowed to air out like that means we’re in Trump’s head as he churns over the Big Lie. Once again: Does he really think he won Georgia, i.e., that it was MAGA land? Or did he simply want Georgia officials to pretend that he’d won so he could stay in the White House?

The title of “Frankly, We Did Win This Election”: The Inside Story of How Trump Lost does keep Trump’s Big Lie securely in quotation marks, and corrects the record with its subtitle. But elsewhere in the book, Bender prolifically recaps the inane banter among Trump and his cronies while also reproducing some of Trump’s most persistent lies about, for example, the size of his rallies. “Nobody has seen anything like it ever,” Bender quotes Trump saying. “There has never never been anything like it.” (Bender, to be fair, points out that Trump hurts himself when he imagines that his distorted apprehension of crowd size is more accurate than the polls that predicted he’d lose the election.)

During the 2016 campaign, cable news channels aired Trump’s rambunctious campaign rallies live, and did nothing to correct his lies. In those days, his whoppers seemed so self-refuting that they could pass as reality-TV bacchanalia. Like Alex Jones, whose lawyer has called him a “performance artist,” Trump’s Barnumism was left unchecked for years simply because nothing as appalling had ever been seen in presidential politics. After five years, we’ve become inured to Trump’s lies, and many of us can recite them as if they are an anthem-rock chorus. Fact-checking, by contrast, requires complexity and pedantry; no one chants Daniel Dale’s brilliant fact-checking live-tweets at Jones Beach.

Trump is simply a narrative migraine. To write a monograph about a figure whose speech and actions don’t comport with identifiable beliefs—much less with reality—is to get in deep with a flailing, splintered, and antisocial mind. Grisham, Trump’s former press secretary, quotes several of Trump’s non sequiturs, including some trash talk about the mother of a prime minister. These choice quotes stop her story like a record scratch. And there’s always a reaction shot: Grisham agape at the audience, reflecting on her own WTF. She quotes Trump’s bunk less to correct or satirize him than to render her own chronic bafflement at the former president’s “batshit things.” It hits the spot.

Usually, depth psychology—the theory that there are distinct emotions, sensations, and needs somehow “under” one’s personality—is steady ground on which to build a portrait. But with Trump, it falters. Does he even have an interior life? In 1997, in an astute profile of Trump in The New Yorker, Mark Singer concluded that his subject leads “an existence unmolested by the rumbling of a soul.” The British writer Nate White also defines Trump by absences: “He has no class, no charm, no coolness, no credibility, no compassion, no wit, no warmth, no wisdom, no subtlety, no sensitivity, no self-awareness, no humility, no honor, and no grace.”

If the afterwords and acknowledgments of all these books are any guide, the authors seem entirely spent by effort. No wonder. The skull of Donald Trump, where delusions and desperation clamor for nourishment like hungry ghosts, is a grim place to spend time. Other readers may have chosen to leave these disturbing books on the shelf; me, I’m grateful that so many observers concluded, as Grisham did, “I have to get this all out so I can process, in my own mind, what the hell happened.”

In their various idioms, Bender, Grisham, Leonnig and Rucker, Wolff, and Woodward and Costa have shed collective light on what the hell happened. And they’ve done a supreme public service simply by etching the events of America’s bleak recent history into the record, where they will be more difficult for Trump and his heirs to lie about in the years ahead. When Condoleezza Rice recently urged Americans to “move on” from the January 6 insurrection, all I could think was, No, no, no, don’t move on; read these books. And when Trump runs again in 2024, remember that those who forget history are condemned—ah, but you know the rest.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.