When I was doing research for my book A World of Ideas, I learned that the mid-century European movement known as Theater of the Absurd had an interesting lineage. Some early Church Fathers held that the key Christian belief, that God became mortal in order to suffer for humanity, is too absurd to have been invented, so it must be true.

That credo was pounced on by the father of Existentialism, Søren Kierkegaard, who argued that since faith is fundamentally irrational, we must either blindly believe, or fully embrace the ambiguity and uncertainty of our existence. That worldview was put on the stage by the likes of Samuel Beckett and Eugène Ionesco in plays that enacted existential futility with nonsense, illogic, contradiction, irony and above all repetition: the pointless cycle of activity that we paint with meaning.

Ionesco’s best-known work, The Chairs, playing at Shakespeare & Company through Oct. 31, is a classic of the genre. It premiered in 1952, the year before Beckett’s Waiting for Godot was first staged. Comparisons are inevitable.

An ancient couple, known only as Old Man and Old Woman, are living in bleak isolation in what seems to be a post-apocalyptic time in which all of civilization – or at least Paris – has been destroyed. They are eagerly awaiting the arrival of the survivors, an assortment of guests they’ve invited to hear a mysterious “message” from the Old Man that will save the world, or “what’s left of it.”

An ancient couple, known only as Old Man and Old Woman, are living in bleak isolation in what seems to be a post-apocalyptic time in which all of civilization – or at least Paris – has been destroyed. They are eagerly awaiting the arrival of the survivors, an assortment of guests they’ve invited to hear a mysterious “message” from the Old Man that will save the world, or “what’s left of it.”

Their memories of 75 years together are indeed repetitive, contradictory and nonsensical. The Old Man keeps beginning a story without ever finishing it. The Old Woman remembers her husband’s devotion to his parents while he recalls letting his mother die in a ditch. When he laments a wasted life with so many could-have-beens, his wife loyally reminds him that he’s General Factotum – a Jack of all trades (but master of none).

The guests arrive – an elegant Lady, an military Colonel, an old flame of the Old Man’s, a crowd of reporters, “all the artists, all the property owners, everybody who is a little intellectual,” and finally the Emperor – all of them invisible to us but not to the hosts, who progressively fill the stage with chairs to seat them all. A folie à deux, certainly, but after all, we are sitting there in the theater, and they act like they don’t see us. Who are the real invisibles? (Though it’s not stressed in this production, a metatheatrical thread runs through absurdist theater.)

Ionesco subtitled his play “a tragic farce.” The physical commotion and verbal non sequiturs are ripe for comedy, the couple’s hopeless illusions the stuff of tragedy. In the end, they meet in the middle. We’re neither in stitches nor in tears, but left with more questions than answers, more ambiguities than certainties – just like life.

Ionesco subtitled his play “a tragic farce.” The physical commotion and verbal non sequiturs are ripe for comedy, the couple’s hopeless illusions the stuff of tragedy. In the end, they meet in the middle. We’re neither in stitches nor in tears, but left with more questions than answers, more ambiguities than certainties – just like life.

In a program note, Warwick answers the implied question “Why this play now?” by recalling last year’s lockdowns. “Isolated from family and friends … having imaginary conversations in our head… a perfect description of life in general recently.”

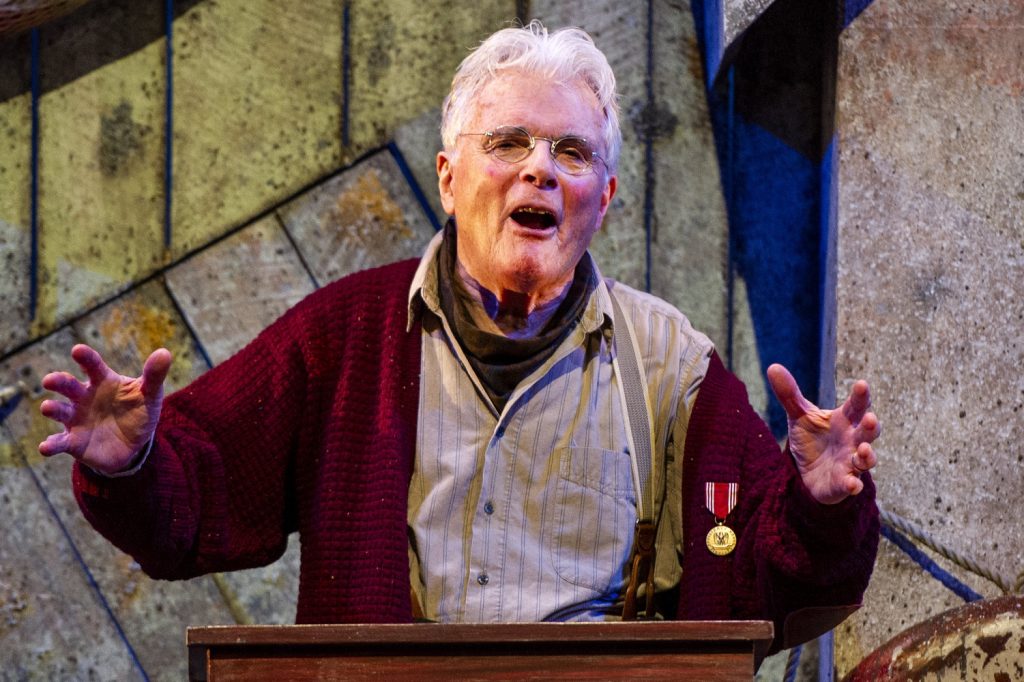

Shakespeare & Company veteran Malcolm Ingram gives the Old Man a tottering dignity, querulous and, as King Lear put it, not in his perfect mind, but single-minded in his quest to complete his life’s work. Barbara Sims’ Old Woman is almost heartbreakingly sweet and supportive, a willing hostess and “helpmeet,” as he calls her, not only ready but eager to hear his unfinished story for the umpteenth time.

Both Warwick and Ingram are English, and Sims dons a convincing accent. Perhaps it’s the Britishness that lends a sense of well-behaved reticence to the proceedings. Voices are seldom raised, there’s hardly a crack in the couple’s unconditional love for each other, and few in their obsequious courtesies to the guests (there is some consternation when the Colonel is apparently getting fresh with the Lady).

Both Warwick and Ingram are English, and Sims dons a convincing accent. Perhaps it’s the Britishness that lends a sense of well-behaved reticence to the proceedings. Voices are seldom raised, there’s hardly a crack in the couple’s unconditional love for each other, and few in their obsequious courtesies to the guests (there is some consternation when the Colonel is apparently getting fresh with the Lady).

This approach is true to the play’s straight-faced affect, though I would like to have seen more variety in pacing and more hectic agitation as the crowd of visitors and chairs swells. And I’m unsure what to make of the ending.

A professional Orator has been hired to deliver the world-saving message on behalf of the Old Man. When he arrives and takes the podium, the script says, he’s revealed as a deaf mute who utters a few unintelligible sounds before writing a cryptic word and a final “Adieu” on a blackboard.

In a recent interview, the director said this representation of a handicapped person “might have worked 70 years ago … but if Ionesco was alive today, he would cut that.” So Warwick has done just that, replacing the actor with an umbrella and the blackboard with a banner dropped from the flies.

I fear that might not be very clear to someone who doesn’t know the author’s original. The same goes for the couple’s final exit after the Orator is introduced and the Old Man declares his mission accomplished: a double suicide that’s explicit in the script but only implied here.

Photos by Daniel Rader

In the Valley Advocate’s present bi-monthly publication schedule, Stagestruck will continue to be a regular feature, with additional posts online. Write me at Stagestruck@crocker.com if you’d like to receive notices when new pieces appear.

Note: The weekly Pioneer Valley Theatre News has comprehensive listings of what’s on and coming up in the Valley and beyond. You can check it out and subscribe (free) here: http://www.pioneervalleytheatre.com/

The Stagestruck archive is at valleyadvocate.com/author/chris-rohmann

If you’d like to be notified of future posts, email Stagestruck@crocker.com