Garcia Discusses Sequencing and the CARD Trial in Patients With CRPC

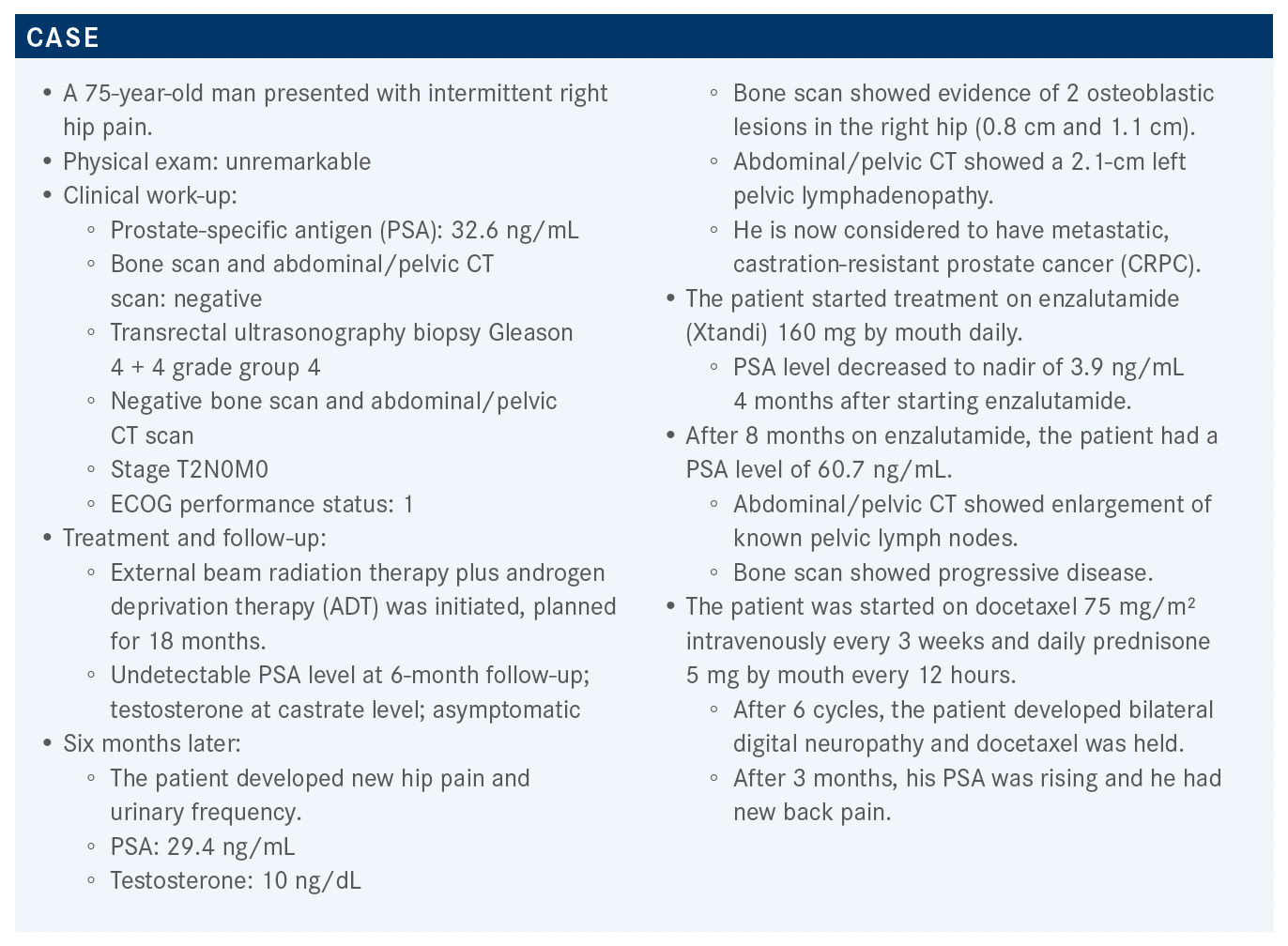

After 8 months on enzalutamide, a patient with castration-resistant prostate cancer had a PSA level of 60.7 ng/mL. The abdominal/pelvic CT showed enlargement of known pelvic lymph nodes, and a bone scan showed progressive disease.

Jorge A. Garcia, MD

During a Targeted Oncology Case-Based Roundtable event, Jorge A. Garcia, MD, division chief, Solid Tumor Oncology, George and Edith Richman Distinguished Scientist Chair, director, GU Oncology Research Program, UH Cleveland Medical Center, and professor, Medicine and UrologyCase Western Reserve University School of Medicine, discussed a 75-year-old man with castration-resistant prostate cancer (CRPC).

Targeted OncologyTM: What do you think of the patient’s options now?

GARCIA: NGS testing, whatever platform you decide to use, demonstrated no actionable mutations. Only 45% of you decided to test; I assume that 45% of you will change your treatment if you have DNA repair deficiency or microsatellite instability [MSI]. This leads me to believe the other half probably would have treated regardless with chemotherapy or radium 223 [Xofigo].

[According to] the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, even in this case, the data are level 1 evidence for cabazitaxel [Jevtana].1 We have abiraterone acetate [Zytiga] data, based upon the COU-AA-301 trial [NCT00638690], which is the first trial that led to the approval of abiraterone in the postdocetaxel space. It didn’t include prior [treatment with] enzalutamide, but that doesn’t exclude it here. With the ALSYMPCA trial [NCT00699751] data, we allow patients who have received prior chemotherapy, and also chemotherapy-naive patients [to receive radium 223]. So I think these data will [apply to] any of those patients. Abiraterone, cabazitaxel, and radium 223 will be acceptable.

Do you feel comfortable giving cabazitaxel to someone who had difficulties with adverse events (AEs) with docetaxel?

The grade 3 and 4 neutropenia with docetaxel can be seen in up to 12% [of patients].2 With cabazitaxel, [grade 3 or higher neutropenia] was in the [45%] range.3 That’s why we give growth factor support the day on or the day after chemotherapy. So, yes, I would be concerned about that. I don’t think prior hematologic toxicity predicts subsequent neutropenia or thrombocytopenia or lack thereof. But this patient received radiation, is on ADT, has bone disease, [and had] chemotherapy. More than likely, this patient would be at risk for a great incidence of neutropenic fever, anemia, or thrombocytopenia.

Would you use the combination of mitoxantrone/ prednisone for this patient?

Mitoxantrone was approved back in the 1990s [because of] the Canadian data. We replicated these data, and it was approved in the United States because it made patients feel better, not because it made them live longer.4 The SWOG 99-16 trial [NCT00004001] and the TAX 327 trial compared docetaxel against mitoxantrone, then picked mitoxantrone for survival, so [the sequence] became docetaxel followed by mitoxantrone. Then the TROPIC trial [NCT00417079] randomized second-line patients who progressed on docetaxel to either cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone.5 Cabazitaxel beat mitoxantrone for survival, so the sequence became docetaxel, cabazitaxel, then mitoxantrone. I still use mitoxantrone for a very select group of patients, but the reality of it is you do it for palliative intent, not because of survival benefit.

What are the data behind using cabazitaxel in patients with prostate cancer?

The data were presented back in 2019 at the European Society for Medical Oncology [annual meeting], and then de Wit et al published it in New England Journal of Medicine the same year.3 The CARD trial [NCT02485691] looked at sequential or switching therapy, if you will. It’s a small trial, but it’s a very definitive trial, at least for me. [Investigators enrolled approximately] 255 patients with metastatic CRPC who had progressive disease within 12 months on prior androgen receptor inhibitors before and after docetaxel. [It was] very similar to this [patient’s case]. They were randomized 1:1 to either cabazitaxel vs abiraterone or enzalutamide based upon what they had as a prior oral agent. The primary end point was radiographic progression-free survival [rPFS] based upon imaging. Secondary end points included survival, PSA, tumor response, PFS, and so forth.

A significant proportion, almost one-third of the patients, were aged 75 years or older; about 60% of patients were Gleason 8 or greater. The baseline of patients based upon the prior therapy, abiraterone or enzalutamide, was pretty consistent with what we see in practice. [Approximately] 50% of the patients had received docetaxel before.

How did patients respond on the CARD trial?

When you look at rPFS based upon the scans, there was a median difference of 8 vs 3.7 months with a hazard ratio of 0.54 [95% CI, 0.40-0.73] and median of 56% relative risk reduction of progressing by scans. If you have seen cabazitaxel, it was quite compelling, in my opinion.3

The subset analyses were not powered statistically to demonstrate the difference between subgroups. But with a few exceptions such as visceral disease and type of progression, most patients on trial appear to benefit from chemotherapy compared with abiraterone or enzalutamide.

The overall survival data, which was a secondary end point of this trial, were compelling to me. I use these data to tell patients why I would not switch them to an oral agent; as in the past, I would have done it just by virtue of tolerability and AEs. Now, with these data, in my view, it’s a compelling argument to tell the patients, “I know cabazitaxel may be a bit more toxic compared with an oral agent, but if you look at the data, they are quite compelling for outcome improvement compared with oral therapies.” There was a median difference of 2.6 months, but there also was a hazard ratio for death of 0.64 [95% CI, 0.46- 0.89], with a statistical P value [.008].

The PFS was encompassed in radiographic and symptomatic progression or death from any cause. [Cabazitaxel had a median PFS of] 4.4 vs 2.7 months with androgen receptor therapy….The hazard ratio is much more telling about the true effectiveness of an agent such as that. For the entire patient population across the trial, you can see a risk reduction of almost 48% for PFS in favor of cabazitaxel.

Not surprisingly, PSA responses were almost 3 times greater—a reduction of almost 3 times greater in favor of cabazitaxel for those with objective evidence of disease.6 It’s not surprising to me this late in the game. When you look at pain by pain scores, almost half of the patients see improvement with cabazitaxel as compared with those who got oral therapy. I think we have come to realize that when you have someone with really symptomatic prostate cancer, very few things can really control their symptoms, but one of the things that can do it really well, when it works, is chemotherapy.

The preplanned analysis also demonstrated that you could delay skeletal symptomatic events. In fact, the median delay hasn’t been reached for those patients on cabazitaxel compared with those patients who receive oral therapy, which is around 16.7 months [P = .05].

What was the safety and quality-of-life (QOL) profile for cabazitaxel in patients with CRPC?

None of these agents comes without a price. For cabazitaxel, any grade 3 or greater AE was around 56% vs 52% [with abiraterone or enzalutamide]; no major differences.3 However, if you look at AEs that lead to treatment discontinuation, it was [more than] twice the number for cabazitaxel [19.8 vs 8.9%], which is not surprising for me in [this] context.

The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Prostate probability of QOL deterioration within 3 months, if you received cabazitaxel vs abiraterone or enzalutamide, is quite compelling, at least in my opinion. You may have suboptimal symptom control, and clinical deterioration is greater for patients who receive an oral therapy.⁶ So, when I look at these data, I think, not only am I more likely to make you live longer, but I’m also more likely to allay your progression. By default, patients are not likely to be compromised by progressive disease and symptomatic disease if they get cabazitaxel over an oral agent.

How does the CARD trial population compare with the TROPIC trial population that originally got cabazitaxel approved?

When we did the TROPIC trial, we didn’t allow abiraterone or enzalutamide because they were not, at the time, [approved]. It was all prior chemotherapy-refractory patients, but not abiraterone or enzalutamide. TROPIC randomized cabazitaxel against mitoxantrone. We also did 2 additional trials looking at cabazitaxel higher dose— the standard dose at the time, 25-mg/m2 dose against the 20-mg/m2 dose. Those data demonstrated that the 20-mg/m2 dose was not inferior to the 25-mg/m2 dose.7

In the CARD trial, did all patients progress on docetaxel before receiving cabazitaxel, abiraterone, or enzalutamide?

This trial was for patients who have had prior chemotherapy but who also have received prior oral agents.3 The only reason why patients needed to move into subsequent therapy was if they had progressive disease. What I don’t know is what is the mechanism of progression. I don’t know if those [patients] were progressing by PSA, clinically or radiographically, but every patient enrolled on the CARD trial had progressive disease. The question is: Was it progressive immediately after docetaxel, or was it progressive immediately after the oral agent and the sequence of how they received?

This trial really addressed the question of sequential therapy and switching to chemotherapy. Patients have received chemotherapy followed by oral therapy, [and] some have received oral therapy followed by chemotherapy.

For a patient with low progression and no symptoms, do you think cabazitaxel would have any advantage?

I think that most of us would favor a cytotoxic [agent] when someone has symptomatic progression. The AFFIRM data [NCT00974311] that led to the FDA approval of enzalutamide in the postdocetaxel space didn’t restrict based upon symptomatic progression, and the greatest [overall survival] hazard ratio in the postdocetaxel space is in those data: 0.63.8 If you look at abiraterone in COU-AA-301, [there was] survival improvement, symptomatic improvement, and rPFS improvement after docetaxel.9 So even patients with symptomatic disease, when we didn’t have cabazitaxel, still benefited drastically from oral therapy.

In fact, there is an argument to be made. Some physicians will tell patients, “If you have so much symptomatic disease, and you have already seen 1 oral agent and chemotherapy, you may be a bit beat up by treatment, also by disease. Let me put you on an oral agent, so at least I don’t run you down through toxicities of cabazitaxel.” That’s another way of thinking of it, but I would argue that for symptomatic patients, most of us [prefer] cytotoxic agents.

What do you think of the overall CRPC setting and sequencing the available therapies?

The biology of metastatic prostate cancer, where you have castration-sensitive or castration-resistant disease, is quite complex and heterogeneous. It is very important for us to understand this is biology; although we’ll make significant effort in the field, I think we’re still pretty short with regards to mechanisms of resistance. Because, at the end of the day, there are 5 to 7 lines of therapy that we have. All those agents were developed simultaneously, if you will, in parallel. None of these agents has been compared head-to-head, with exception, perhaps, of the CARD data, or chemotherapy against chemotherapy.

When you look at the choices, we really don’t understand the sequence by virtue of biology, because we don’t know how patients become resistant biologically, and we don’t know how to overcome that biologic resistance. So, most of us continue to use clinical aspects to make those decisions as to how we sequence therapies. It’s also fair and transparent to say that most [clinicians] will probably start with an oral agent or maybe layer sipuleucel-T [Provenge] for those who believe in sipuleucel-T, and then you move to an oral agent. Then, you start moving to chemotherapy, and then you start dissecting chemotherapy against radium 223, and then maybe you even start thinking about other agents in that context.

Therapeutically, the sequence is really important as you treat these patients. I think that understanding your goals of care—survival, rPFS, symptomatic or objective progression—is key. I think PSA is relevant, as well, when you use oral agents, but at the end of the day it’s about outcome improvement defined by how they feel. Can you delay progression of patient’s symptoms? Can you give them the least AEs and maintain QOL while they live longer? That is the big key here.

REFERENCES:

1. NCCN. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Prostate cancer, version 1.2022. Accessed September 23, 2021. https://bit.ly/3uadtsO

2. Sweeney CJ, Chen YH, Carducci M, et al. Chemohormonal therapy in metastatic hormone-sensitive prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(8):737-746. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1503747

3. de Wit R, de Bono J, Sternberg CN, et al; CARD Investigators. Cabazitaxel vs abiraterone or enzalutamide in metastatic prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2506-2518. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1911206

4. Green AK, Corty RW, Wood WA, et al. Comparative effectiveness of mitoxantrone plus prednisone versus prednisone alone in metastatic castrate-resistant prostate cancer after docetaxel failure. Oncologist. 2015;20(5):516-522. doi:10.1634/theoncologist.2014-0432

5. de Bono JS, Oudard S, Ozguroglu M, et al; TROPIC Investigators. Prednisone plus cabazitaxel or mitoxantrone for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer progressing after docetaxel treatment: a randomised open-label trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9747):1147-1154. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61389-X

6. Fizazi K, Kramer G, Eymard JC, et al. Quality of life in patients with metastatic prostate cancer following treatment with cabazitaxel vs abiraterone or enzalutamide (CARD): an analysis of a randomised, multicentre, open-label, phase 4 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(11):1513-1525. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30449-6

7. Eisenberger M, Hardy-Bessard AC, Kim CS, et al. Phase III study comparing a reduced dose of cabazitaxel (20 mg/m2) and the currently approved dose (25 mg/m2) in postdocetaxel patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer—PROSELICA. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(28):3198-3206. doi:10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1076

8. Scher HI, Fizazi K, Saad F, et al; AFFIRM Investigators. Increased survival with enzalutamide in prostate cancer after chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(13):1187-1197. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1207506

9. Fizazi K, Scher HI, Molina A, et al; COU-AA-301 Investigators. Abiraterone acetate for treatment of metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer: final overall survival analysis of the COU-AA-301 randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(10):983-992. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70379-0

First Real-World Data on Second-Generation AR Inhibitor Use in nmCRPC

September 18th 2023A review of real-world data from the DEAR study of darolutamide, enzalutamide and apalutamide for the treatment of nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer is given by Alicia Morgans, MD, MPH.

Listen

Novel Approaches Focus on Limiting Toxicity in Older Patients With ALL

April 22nd 2024The major challenges for clinicians treating older patients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia surround the emergence of resistance to existing therapies and the toxicities associated with current chemotherapies.

Read More