Jimmy Carter is having another well-deserved moment in the sun. Already the longest-living president in our history, he recently turned 97. Two recent Carter biographies by Jonathan Alter and Kai Bird have helped refurbish his image. And, of course, Carter’s own actions—his miraculous brain cancer remission a few years ago, his continuing to speak thoughtfully on issues of the day, and, especially, his exemplary post-presidency—have helped to remind Americans why they took a gamble and elected “Jimmy Who?” in 1976. Carter isn’t without ego. What president is or should be? His presidential campaign autobiography was titled Why Not the Best? But the juxtaposition with the egomaniacal Donald Trump, which has raised the standing of all ex-presidents, has best served Carter, putting his life of service in relief. His chosen lifestyle—no Mar-a-Lago, no massive buck raking—stands in vivid contrast to Trump and, to a lesser extent, George W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and Barack Obama. They enjoy the lavish speaking circuit and other celebrity perks that Carter has always eschewed.

One quality Carter had that’s most welcome now was his capacity for healing. This was the animating spirit, the raison d’être behind his 1976 candidacy. It was to bind the wounds of Watergate with a government, as Carter said, as honest as its people. With few exceptions, he kept his word.

Some actions that he took immediately as chief executive deserve fresh notice. I’m thinking of those first gestures the 39th president made after taking the oath of office in January 1977. One was Carter thanking his predecessor Gerald Ford, the Republican he’d narrowly beaten, for “all he has done to heal our land.” It was a bighearted move, one that stands in contrast with Trump’s churlish decision not to attend this year’s inauguration and his unconscionable actions to overturn the 2020 election.

Before leaving the Capitol, the newly sworn-in Carter took his own stand for a healed nation. He quietly signed an executive order granting a blanket pardon to those tens of thousands of Americans who had illegally evaded the draft. It addressed the divide that cut even deeper than Watergate into the country’s soul: Vietnam.

We speak and write so often today about the need to end our grinding divisions in this country. We ask—at least we claim to ask—for leaders who will lower the temperature of our political discourse, to stop their constant ignition of our cultural and class warfare.

Here, Jimmy Carter was a new president doing just that. He was telling the roughly 100,000 young people who had broken the law and forsaken their country to come home. As the historian Douglas Brinkley wrote of the draft evader pardon, “It gave people their lives back.”

That act of leadership also told the country at large that it was time to move on from Vietnam, to stop the punishment and the hatred that went with it.

Carter issued that mass pardon knowing the political hazard. The home front battle over the war was still red hot. The violence at the 1968 Democratic convention in Chicago was still vivid in public memory; the fault line between “longhairs” on campus and “hard hats” still defined the partisan culture. The humiliation of the helicopters leaving the roof of the American embassy in Saigon was itself less than two years old.

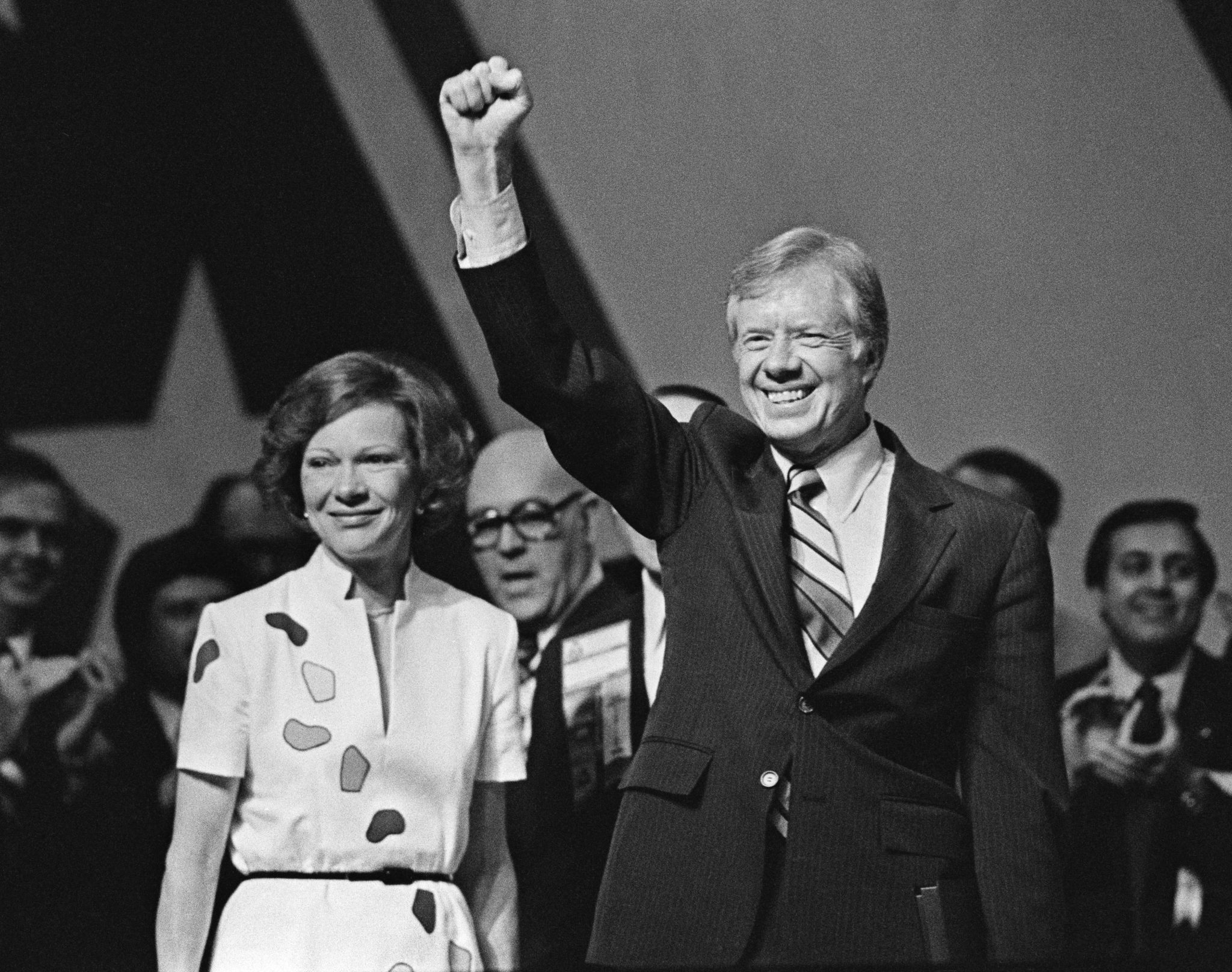

As Alter notes in his splendid biography, Carter had supported the war until 1974. But in accepting the Democratic nomination two years later, he embraced amnesty and allowed the activist veteran Ron Kovic (played by Tom Cruise in the film Born on the Fourth of July) to address the convention. While many Americans, including the widow of the recently deceased and beloved Senator Phil Hart of Michigan, had pleaded with Ford to pardon draft resisters, the Republican president had refused. Carter stuck by his 1976 convention pledge and signed the executive order. He did so after having been booed over the proposed pardon at an American Legion convention during the fall campaign.

But with all that in the background, Carter’s decision to end the banishment of the illegal war protesters, most of whom had gone to Canada, was generally accepted. The predictable outrage arose from the predictable quarters but soon subsided.

It’s good to recall that early moment of leadership, especially as we begin to weigh the overall Carter presidency. We discuss so often these days why our political life is so polarized. Why can’t our politicians find ways to end disputes rather than worsen them? Why can’t our leaders make decisions even if there is a political cost? Where are the peacemakers, the profiles in courage?

Whatever else can be said about the Carter presidency, these were the core motives driving the man himself. It won him credit, and it also cost him, but it was the hallmark of his presidency.

At Camp David in 1978, Carter helped to heal the divide between Egypt and Israel, Anwar Sadat and Menachem Begin, and did much of it himself. The Egyptian leader had taken a risk for peace by flying to Israel, addressing the Knesset, and then beginning a process that led to the Camp David Accords. Sadat would pay for his peacemaking with his life. But it was Carter who was the necessary healer who closed the deal in the Catoctin Mountains of Maryland, keeping Begin and Sadat isolated at the presidential retreat for all those days, enduring the vitriol, all the temper tantrums. Together, the three leaders worked out a historic settlement between two countries that had been at war four times since Israel’s founding in 1948.

The peace endures because it made sense for all sides, including that of the United States. It was a matter of tough-minded nation-to-nation-to-nation advantage.

There was, too, a moment of moral romance during those days at Camp David. It’s when, performing as both mediator and host, Carter took his two guests to nearby Gettysburg. It was a simple human act. The Georgian, who had inherited a southerner’s memory of defeat, wanted his two guests to see the cost that we Americans had suffered in war. It was pure Jimmy Carter, believing that he could elicit each man to take a huge political risk.

He once told me how it stirred him emotionally when the tough-minded Israeli prime minister stood there at the spot where Abraham Lincoln gave his great address—and delivered it from memory.

There was courage in that Israeli-Egyptian treaty, also realpolitik. It was a land-for-peace deal, with Israel giving up the Sinai, forcibly removing settlers. The two countries have honored the treaty ever since, even with the brief reign of the Muslim Brotherhood in Cairo, because each side needed it. American support, save for occasional bumps, has been unwavering to both countries.

The same can be said of Carter’s decision to sign the Panama Canal Treaty, which avoided a violent conflict along the waterway that could have lingered for decades. It wasn’t just about ships and cargo. It was about continuing the work of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “Good Neighbor” policy and John Kennedy’s Alliance for Progress to extend a hand to Central and South America.

Even Carter’s handling of the Iranian hostage crisis of 1979 deserves a historic look back. He had the choice of taking us to war but decided instead to limit the conflict to getting our diplomats safely back home. Even on the night before he lost reelection in 1980, he could have turned righteously belligerent against the Iranian revolutionary government. Ultimately he decided it would get him some votes, but at the cost of the hostages’ lives. While the previous spring’s disastrous Desert One rescue operation had shown that Carter, the Annapolis graduate and last Democratic president to serve in uniform, was no pacifist, he resisted the pull to pound his chest.

History will offer its verdict on this good man. One reckoning we render already is that Carter, now approaching his personal centennial, stuck to his personal code. He sought peace, avoided war, and tried, even against his political interest, to do what he believed would unite us.

It began with that decision in the first moments of his presidency to face the outrage of the armchair generals and give thousands of young Americans their lives back.