Democrats Are Ready to Send Steve Bannon to Jail

If Democrats want answers, they’ll need to enforce their subpoenas in the face of Trump allies’ defiance. They say that’s just what they plan to do.

James Carville is furious. “It’s the LAW!!! If you do not enforce it, Dems will look as weak as people think they are,” he texted me earlier this week. “I would ask if we could use DC jail for Bannon.”

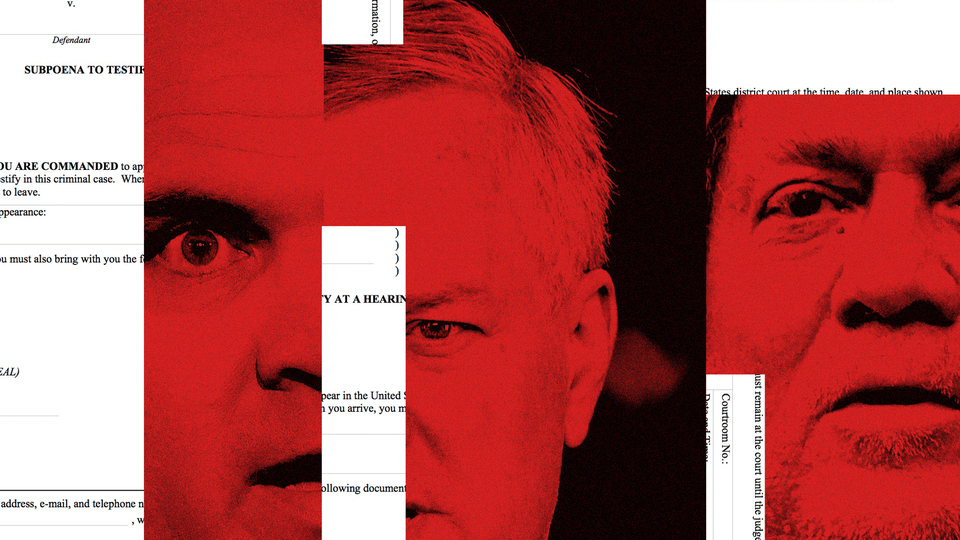

What has Carville itching to put former President Donald Trump’s ex-adviser behind bars? Defiance. The special congressional committee charged with investigating the January 6 insurrection gave former Trump White House officials Steve Bannon, Mark Meadows, Kash Patel, and Dan Scavino until the end of this week to comply with its subpoenas for testimony and records. Bannon has so far refused to cooperate.

Congressional Democrats, who control both chambers and have a majority on the January 6 committee, can ask the House or Senate sergeant-at-arms to arrest Bannon. Yesterday afternoon, though, Representative Bennie Thompson, the Mississippi Democrat who chairs the committee, announced that he will pursue a more moderate path: Next week, the committee will vote on whether to refer Bannon to the Justice Department for potential criminal prosecution.

“We fully intend to enforce” the subpoenas, Representative Adam Kinzinger of Illinois, who is one of two Republicans on the special committee, assured me. “That doesn’t come with the snap of a finger, but we will get to the bottom of these questions and pursue all avenues.”

Democrats want to uphold norms of interparty civility while also preventing Trump and his buddies from completely undermining democracy. But time is running out. The January 6 committee is one of Congress’s last chances to narrate the Capitol riots and the Trump administration’s efforts to subvert the peaceful transfer of power. The only way to fight fascism is with narrative, Masha Gessen, the writer and activist, once told me. The select-committee probe presents a real opportunity to do just that.

Enforcing the committee’s subpoenas isn’t a controversial idea, Representative Eric Swalwell of California told me. “We must enforce congressional subpoenas not just for holding insurrectionists accountable but to show everyone in America that we all follow the same rules,” he said. “If Bannon and company are above the law, why wouldn’t nonpublic figures toss their lawful subpoenas in the trash?”

Perhaps Bannon thinks that the committee won’t follow through, or that jail time might martyr him. He’s dodged consequences for alleged misconduct before. Last year, he faced prison for his role in the “We Build the Wall” scheme, which prosecutors said was fraudulent, but Trump granted him an 11th-hour pardon. At least he’s had some time to think about what he might have to pack.

The committee had hoped to depose Bannon, Meadows, Patel, and Scavino this week, according to lawmakers, but some members of that group have been more cooperative than others. “While Mr. Meadows and Mr. Patel are, so far, engaging with the Select Committee, Mr. Bannon has indicated that he will try to hide behind vague references to privileges of the former President,” Representative Liz Cheney, a Wyoming Republican, wrote in a joint statement with Thompson.

Bannon seems likely to continue resisting his subpoena. “The executive privileges belong to President Trump,” and “we must accept his direction and honor his invocation of executive privilege … Mr. Bannon is legally unable to comply with your subpoena requests for documents and testimony,” Bannon’s attorney, Robert Costello, wrote in a letter to the committee earlier this month. Bannon hasn’t worked in the executive branch since August 18, 2017, more than 1,500 days ago. And Trump is no longer the chief executive—he’s just some guy playing golf at his country club. The Biden administration has already waived executive privilege for the Trump-era documents that the January 6 commission was seeking.

The committee is in agreement about pursuing criminal referrals for witnesses who refuse to cooperate with their subpoenas. “We now have a Justice Department committed both to the rule of law and to the principle that no one is above the law. The January 6 committee … will respond with equal swiftness to those who fail to comply, holding them in criminal contempt and referring them to the Justice Department for prosecution,” Representative Adam Schiff of California told me.

The problem with enforcing congressional subpoenas, though, is that it pits two of the Democrats’ priorities against each other. Democrats have been tasked with both upholding democracy and defending constitutional norms. The norm of the past 90 years has been that congressional subpoenas are honored because the people subpoenaed are honorable. That doesn’t seem likely to happen here. Still, Congress hasn’t jailed a witness since 1934, when it found William P. MacCracken Jr. in contempt for refusing to participate in a Senate investigation into how federal airmail contracts were awarded. MacCracken was “taken into custody by the Sergeant at Arms, although rumor has it that he was held at the Willard Hotel,” according to the The Washington Post. A criminal referral to the Justice Department would likely move much slower than MacCracken’s arrest—and could prove easier to fight. If Bannon can delay long enough, he could simply run out the clock, and hope that Democrats lose control of Congress in 2022.

Because the January 6 committee cannot rely on members of Trumpworld acting honorably, it may have to go further, Joyce Vance, a former U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Alabama, told me. “Historically, the enforcement mechanism for congressional subpoenas to executive-branch employees was as much political as it was legal,” she explained. “In other words, the parties negotiated over the scope of subpoenas, because the political cost of outright defiance was seen as too high. Trump broke that process, convincing his followers that refusing to submit to congressional oversight was a virtue, not a violation of our laws. If Congress can’t regain the ability to enforce its subpoenas in the light of a norm-breaking presidency, its oversight abilities will be extinguished.”

Last year, Congress drafted a resolution to be used with noncompliant members of the Trump administration. It was meant to give congressional subpoenas teeth. “As a police officer, you see a lot of people who think they’re above the law,” Val Demings, one of the sponsors of the resolution, told me. “We called them ‘habitual offenders,’ and the only way to stop them is to hold them accountable. When there’s no enforcement mechanism, it’s no surprise that we see corruption, cover-ups, and contempt towards those of us trying to bring accountability to Washington … No one is above the law, up to and including the president of the United States.”

Will putting Bannon in jail make him tell the truth about what happened leading up to and on January 6? Don’t count on it. Will jail be something Bannon can use for fundraising and publicity? That’s one of his core competencies. But a fight with Bannon over congressional power and criminal referrals, however protracted, could help Democrats too. Drawing more attention to the committee’s investigation and its high stakes isn’t necessarily a bad outcome for those of us who want to preserve democracy. If the January 6 committee can hold widely watched, televised hearings, with or without Bannon, perhaps some of the truth will get through to Americans so far unmoved by what happened early this year. The committee’s power to convince, rather than its power to punish, will matter most.