Complaint alleges ICE tortured African asylum seekers using restraint device during deportation

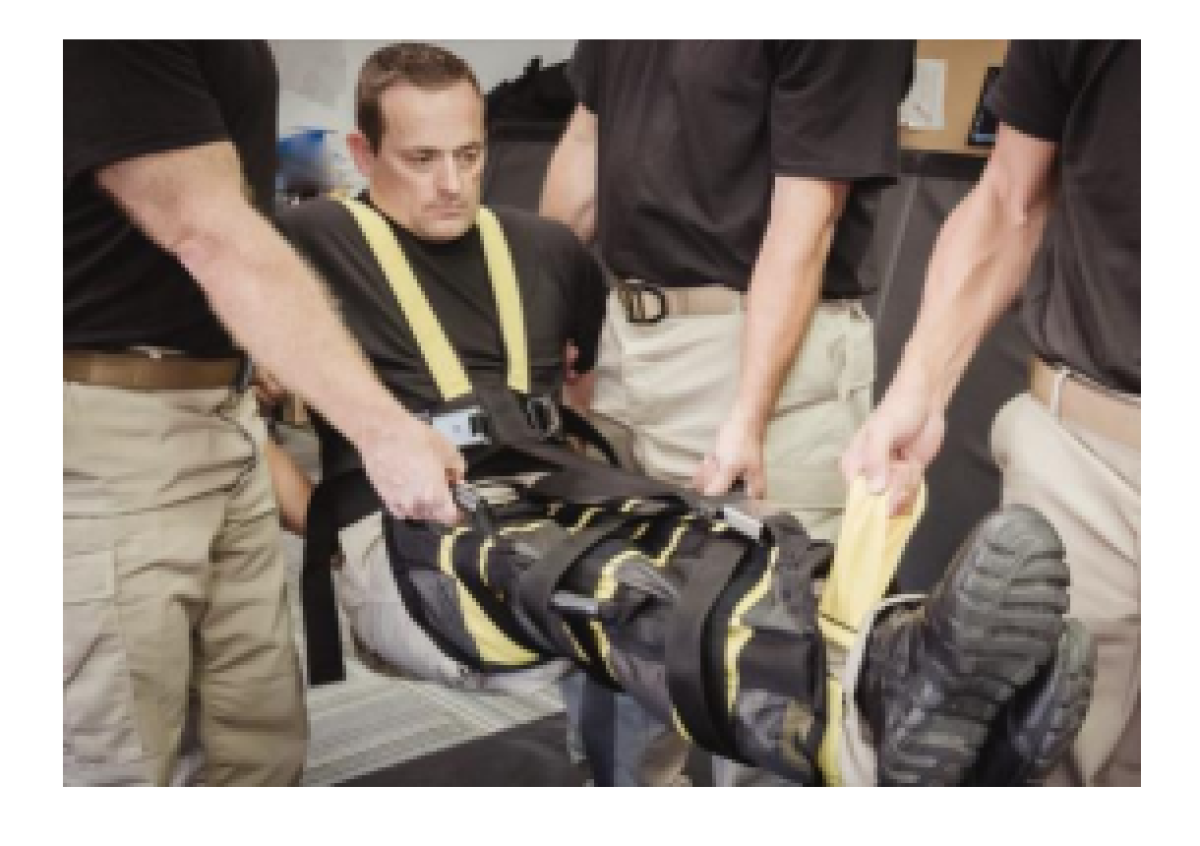

The device, known as The WRAP, placed men from Cameroon and Uganda in stress positions for hours, complaint says

When Godswill entered the San Ysidro Port of Entry in the summer of 2019 to request asylum from his home country of Cameroon, he thought he had finally reached a safe haven.

But what he says happened in U.S. custody, particularly as he was being deported back to Cameroon, left him feeling betrayed.

Before Immigration and Customs Enforcement officials put him on a deportation flight in November 2020, they cinched him into a restraining device called The WRAP, which held his legs tightly straight and together while pulling his head and chest down towards his knees at a sharp angle, Godswill said. Because of his vulnerable situation, he asked to be identified only as the pseudonym given to him in the complaint.

“It’s something I would never wish for my enemy,” Godswill said in an interview. “It is humiliating. It is demoralizing. It is a high degree of torture.”

Godswill is now one of three Cameroonian men who have come forward in a complaint filed Wednesday with the Department of Homeland Security Office of Civil Rights and Civil Liberties about the harm that ICE’s use of The WRAP caused them.

ICE did not respond to a request for comment about the complaint.

What happened to the three men and to others who were too scared to come forward publicly, the complaint says, falls under the definition of torture from the United Nations Convention Against Torture, which the United States signed in 1988.

The complaint also raises the question of whether the treatment was motivated by racism. So far, the only deportees that advocates have identified as having experienced The WRAP were Black asylum seekers from African countries.

In October and November of last year, the Trump administration organized flights to deport Cameroonians en masse.

At the time, several men scheduled to be removed on those flights spoke out against the deportations, saying they would be imprisoned, tortured or even killed upon return to Cameroon, where the francophone, or French-speaking, government has been attacking anglophone, or English-speaking, residents for years.

Some on the flights alleged they were physically forced to sign documents related to their deportations. And now this latest complaint illustrates abuses that the men say occurred in their last moments on U.S. soil.

The complaint alleges that ICE is not using the restraining device as intended by the company that makes it.

The WRAP, created by California-based Safe Restraints Inc., was designed to allow law enforcement officers to restrain someone without holding the person face down, according to the company’s president and CEO Charles Hammond. It is meant to be used to hold someone upright at a 90-degree angle or leaning back slightly.

“The WRAP controls somebody upright so they can breathe and recover without the ability to hurt themselves or hurt others,” Hammond said. “That allows us to give medical care without having to engage in another conflict. It allows the person to deescalate. It’s not a pain tool.”

He said that free training is provided to any law enforcement agency that purchases the restraining device to ensure safe use.

He declined to comment on the complaint or ICE’s use of The WRAP.

The complaint says that ICE officials tightened The WRAP so that the men were forced to sit at a 30- or 45-degree angle, restricting their ability to breathe.

This was particularly problematic for Godswill, who has asthma.

He said he wasn’t resisting ICE orders when he was forced into The WRAP. He had been so anxious about his deportation that he hadn’t eaten for days, and he fell while trying to walk up the stairs to the plane.

Officers dressed in what Godswill described as military attire then put the restraint on him.

“Nobody asked me why I fell. Nobody asked me if I’m OK,” he recalled. “I was obeying whatever they said. I wasn’t resisting them, but they were tying me down. I was crying. I was begging them, saying that they were killing me, but nobody was listening.”

He recalled some officers pushing his back so his head would go down further towards his legs as they tightened the straps. He waited on the tarmac while other deportees boarded the plane. Then the officers carried him “like a bunch of wood,” and “dumped” him onto a set of three seats on the plane, he said. He had to travel sideways because of the device.

“I cried like I’ve never cried before. I cried like a child,” Godswill said. “I believed they were killing me.”

He told the officials that he couldn’t breathe, that he had asthma and that he was being treated for back pain. As with everyone else being deported on the flight, he was already in a restraint — his wrists, ankles and waist were chained together — before he fell. Now, The WRAP was pushing the leg shackles into his skin, cutting him.

One officer eventually adjusted the leg shackle, and a medical staff person puffed medication from Godswill’s inhaler into his mouth, but he remained in the restraint for hours. He saw two other men in the device, though one was removed from the plane before takeoff.

Nearly a year later, he still has back pain from the incident, he said, and he was psychologically scarred as well.

“I don’t know when I’m going to recover from all this pain,” he said. “It’s like it’s a nightmare, but it is real.”

Talking about what happened to him is still difficult, he said, but he agreed to publicize his story because he is still hoping for justice.

“There are some events in life that you try not to remember,” Godswill said. “This was truly a horrible experience.”

A man identified in the complaint as Castillo said that he was put in the restraint while still at an immigration detention center before his scheduled deportation flight. When he learned he was going on the plane, he had told officials that his case was still pending on appeal. Officers responded by putting him in an isolation cell, and then shot him with rubber bullets before placing him in the device, he said.

“It has traumatized me. Right now I still hear the echoes of the gun shots that were being shot at me while I was still in isolation,” said Castillo, who initially requested protection at the San Ysidro Port of Entry in 2018. “I came to U.S. to seek protection and safety. I was never a criminal.”

The third complainant, identified as Ray, said that he was placed in The WRAP and set on the ground outside so other detainees could see him before they got on the plane. He thinks it was a way to intimidate them.

“In Cameroon, I had been beaten with a machete until my feet swelled and bled, and I was struck again and again with a metal belt buckle,” Ray said in the complaint. “In the U.S., I was detained for two years and 10 months. But the day I was put in The WRAP by ICE, I wanted to die. I have never felt such horrible pain.”

Many Cameroonians lost their asylum cases because of a Trump policy that said people who passed through another country on their way to request protection in the United States were no longer eligible. That policy had since been struck down in court, but the court’s decision did not automatically change decisions in cases that had already finished.

Godswill was among those affected by the policy.

Sarah Towle, a member of the leadership team with Witness at the Border, an advocacy organization that documents ICE transportation flights, said many of the deportees she has interviewed were jailed upon their return. Some are still being held.

Still in danger, Godswill and Castillo are living in hiding outside of Cameroon. The complaint asks that they be brought back to the United States to testify in an investigation into how ICE treated them.

Despite what happened, both men said that if given the opportunity, they would still feel safer in the United States than in their home country or where they are living now.

“I feel like I don’t even have a future,” Godswill said. “I can’t say what I wish to happen tomorrow.”

Get Essential San Diego, weekday mornings

Get top headlines from the Union-Tribune in your inbox weekday mornings, including top news, local, sports, business, entertainment and opinion.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.