Oct 08 2021

Hacking the Brain to Treat Depression

A new study published in Nature looks at a closed loop implanted deep brain stimulator to treat severe and treatment resistant depression, with very encouraging results. This is a report of a single patient, with is a useful proof of concept.

A new study published in Nature looks at a closed loop implanted deep brain stimulator to treat severe and treatment resistant depression, with very encouraging results. This is a report of a single patient, with is a useful proof of concept.

Severe depression can profoundly limit one’s life, and increase risk for suicide (affecting 300 million people worldwide and causing most of the 800,000 annual suicides). Depression, like many mental disorders, is very heterogenous, and is therefore not likely to be one specific disorder but a class of disorders with a variety of neurological causes. It also exists on a spectrum of severity, and it’s very likely that mild to moderate depression is phenomenologically different from severe depression. Severe depression can also be in some cases very treatment resistant, which simply means our current treatment options are probably not addressing the actual brain function that is causing the severe depression. We clearly need more options.

The pharmacological approach to severe depression has been very successful, but still not effective in all patients. For “major” depression, which is severe enough to impact a person’s daily life, pharmacological therapy and talk therapy (such as CBT – cognitive behaviorial therapy) seem to be equally effective. But again, these are statistical comparisons. Treatment needs to be individualized.

For severe and treatment resistant depression there has also long been a third therapeutic approach – electrical stimulation. This began in its crudest form as electroconvulsive therapy, where an electrical stimulation was used to induce a generalized seizure. Over the years this technique has been refined, improving patient safety and reducing side effects. It has been found, for example, that using less and less stimulation is still effective. ECT has been shown to be highly effective in about 80% of severe major depression.

There is also a more recent treatment approach called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). This is less invasive, safer, and better tolerated that ECT. It has an overall efficacy of about 50-60%, with about one third of patients have complete remission of depression. Effects last on average for about a year.

The current study reflects what can be seen as the next stage of using electromagnetic stimulation to alter brain function in order to relieve depression. Instead of stimulating large parts of the brain, the goal here is to identify one specific brain region in an individual patient that relieves their depression. This approach has three possible advantages – the stimulation is more precise, the stimulation is individualized to the patient, and the stimulation can be triggered by episodes of depression.

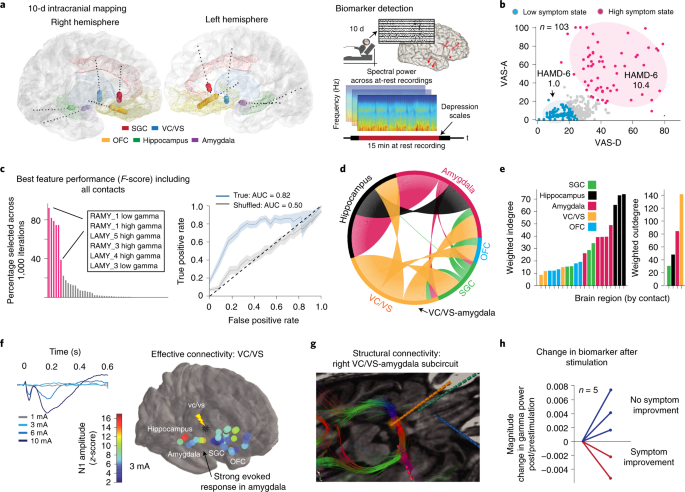

The researchers monitored the patient for 10 days to see if they could correlate brain activity with depression episodes. They found an area of the amygdala that became active at the beginning of depression. They also tested likely stimulation sites, and found one location, the ventral striatum, that consistently reduced depression when stimulated in a dose-dependent manner (always a good sign that a treatment is actually working and not just a placebo or non-specific effect). Once they were convinced they had identified the proper brain regions, they implanted a matchbook size stimulator in the skull and under the scalp. The device detects activity in the amygdala to indicate the onset of a depressive episode, and then stimulates the ventral striatum to reduce the depression (this is called a closed loop system).

The researchers now report on a year of experience with the first patient with this device, and the results are very encouraging. The subject, Sarah, reports to the BBC:

“When the implant was first turned on, my life took an immediate upward turn. My life was pleasant again.

“Within a few weeks, the suicidal thoughts disappeared.

“When I was in the depths of depression all I saw is what was ugly.”

She also reports that she can tell when the device is active because it gives her a boost in her mood. Obviously, this is an N of 1 study with no control group and no blinding. But this is an impressive result for a patient who was completely treatment resistant otherwise. Still, the researchers are appropriately cautious:

Dr Edward Chang, the neurosurgeon who fitted the device, said: “To be clear, this is not a demonstration of efficacy of this approach.

“It’s really just the first demonstration of this working in someone and we have a lot of work ahead of us as a field to validate these results to see if this actually is something that will be enduring as a treatment option.”

I have to point this out, because this quote is in such stark contrast to how charlatans behave, and also how critics unfairly characterize mainstream medicine. A sure sign of a crank is that they will make bold claims based on flimsier evidence. Real scientists, however, point out the limitations of our current evidence, and are focused on what we still don’t know (because that is where future research lies). Those possible limitations include the fact that we don’t know if this approach will replicate in other people. We also don’t know how sustainable the effects might be. The brain is plastic, and over time the stimulations may simply have reduced effect. Further, the optimal stimulation site might migrate over time, or a new brain dynamic may emerge. So we don’t know how sustainable these results will be.

But this is how research works. We have a new technique, so we test it in one subject as a proof of concept – is it safe, practical, and does there appear to be any benefit. The researchers are now fitting two additional subjects, and plan to do nine total. They can then publish a case series, which will give us much greater information about safety and the probability of this approach working. If the treatment is still looking promising, then a larger clinical trial would be appropriate. At some point we cross the threshold where there is sufficient evidence of safety and efficacy to be recommended as a standard treatment, but the research is not over. Then treatment outcomes are tracked over time and compared to other alternatives. It will likely take 20 years before we have a really good idea how effective and sustainable this approach will be.

It seems probable, however, that we will be seeing the overall approach, using electrical or magnetic stimulation of specific locations in the brain, will become more common as the technology advances. This paradigm of treatment of brain disorders could have greater potential than the pharmacological approach, because we are not limited by the inherent lack of specificity of brain chemistry. We can get as precise in our stimulation as the technology allows, without theoretical limit.