Heading out the door? Read this article on the new Outside+ app available now on iOS devices for members! Download the app.

Yogic wisdom teaches us that inversions can have a powerful effect on our balance, both physical and mental. I personally believe that inversions lie at the very heart of yoga asana practice and that there is almost always a modification that can make some variation of an inverted pose possible for almost all students. Inversions in some form should be a part of most students’ practice, where possible.

What is an inversion?

My definition of an inversion is any pose in which the head is lower than the heart. This includes Uttanasana (Standing Forward Bend), Prasarita Padottanasana (Wide-Legged Standing Forward Bend), Adho Mukha Svanasana (Downward-Facing Dog Pose), Setu Bandha Sarvangasana (Bridge Pose), and Viparita Karani (Legs-up-the-Wall Pose), among others.

I think of inversions in two broad categories. The first is an inversion where the head, but not necessarily the rest of the body, is below the heart. The second category consists of inversions that require more strength and flexibility and should be practiced only under the supervision of a well-seasoned teacher: Salamba Sirsasana (Supported Headstand), Adho Mukha Vrksasana (Handstand), Halasana (Plow Pose), Salamba Sarvangasana (Supported Shoulderstand), and Pincha Mayurasana (Forearm Balance).

Why I recommend inversions

My favorite yoga myth is “inversions bring more blood to the brain.” Not so. In fact, the amount of blood in the brain is strongly regulated to stay steady whether we are standing on our feet, our hands, our shoulders, or our heads.

But inversions do affect the blood flow in the body. Holding an inversion can directly benefit the heart by increasing venous return—the amount of blood the heart receives. This usually causes the heart to slow down and rest.

The stillness and internalization of focus cultivated in inversions can help to reduce stress and anxiety, as well as swelling in the legs. Some students also report that regularly practicing inversions has reduced the hot flashes sometimes associated with perimenopause.

The structure of inversions

Our legs and feet are made to bear weight and drive locomotion. In contrast, our forearms, hands, and wrists are not normally weight-bearing. Our hands are not nearly as powerful as our feet, and certainly not as well prepared to hold weight. But inversions often involve some weight-bearing on the head, neck, shoulders, forearms, or hands. It is easy to understand the need for attention when we ask our hands and wrists to hold our whole body’s weight.

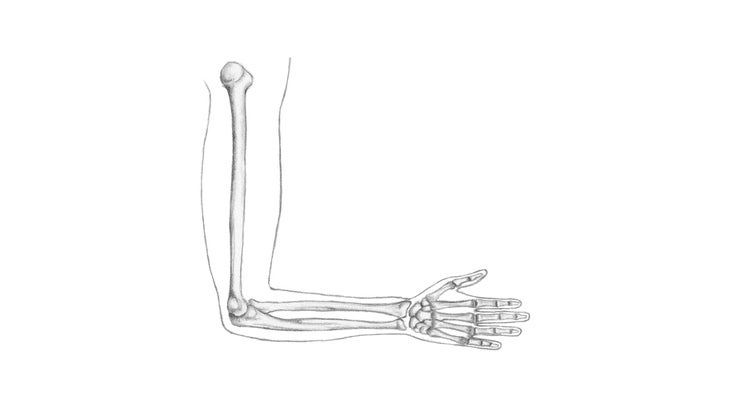

The radius and ulna (the forearm bones) and the humerus (the upper arm bone) connect at your elbow. The ulna, the less mobile of the two forearm bones, curves under the posterior (back) side of the elbow joint to join with the humerus. The radius attaches to the humerus in a way that makes it more mobile. This knowledge comes in handy when you are practicing inversions because it helps you understand the impact that the position of your arms and hands has on weight bearing.

For example, in Supported Headstand, your forearms are neutral (supinated) and your elbow is the primary weight-bearing structure. At the elbow, the ulna is thicker than the radius, creating greater structural stability. This design helps it absorb and distribute more load to and from the humerus.

Mindful placement of your hands and forearms in inversions helps you build a stable foundation for these powerful poses. In Handstand, the weight of the pose goes directly down into your hands. To accommodate this extra weight on your hands and wrists, create an arch in your hand: With your palms flat on the floor, pull the pads of your fingers toward you so that your fingers are arched and only the rims of your hands are on the floor.

Your hands should be shoulder-width apart. If you place your palms in line with your shoulder joints, your clavicle will feel squashed, so widen your arms a bit until you find the alignment where your collarbones maintain their own natural space and shape.

See also: This Sequence Will Help You Practice Inversions Safely

Salamba Sirsasana (Supported Headstand)

Place your mat on the floor with the short end touching the wall. Put a firm blanket on the mat to offer some padding for your head and forearms. (Too thick a blanket will interfere with your stability.)

Come into Tabletop, facing the wall. Then place your elbows underneath your shoulder joints so that your upper arm bones are vertical. Press your forearms firmly into the mat and turn your hands so that your palms face each other. Press the bones of your outer hands firmly into the floor. Interlock your fingers without gripping, so the webbing connects strongly. Shift your weight forward and engage your forearms, hands, and wrists.

Place your head against the inside of your wrists so that your weight is slightly to the front of the top of your head. As you enter the pose, you will naturally roll toward the top of your head and find your balance. Look straight out into the room. Walk your legs in toward your trunk, keeping your knees bent. Kick up with one leg, push off with the other, and immediately take your feet to the wall. Keep your shoulders strongly lifted and your neck long. Keep your breath easy and natural. Turn your legs inward so that the balls of the feet touch the wall and the heels separate. Lift through the balls of your feet.

When you are ready to come down, slowly lower one leg and then the other, and immediately sit back in Child’s Pose.

Safety First: Protect your neck in Headstand

Feeling some pressure on your head in this pose is normal and can be quite pleasant, but if you have any other sensation in your neck, come down out of the inversion at once. You may even want to have your neck checked out by a medical professional such as a physical therapist, chiropractor, or physiatrist.

Unlike most poses, Headstand is not one I recommend you try more than once during a practice. It is a strong posture with deep effects, and one per practice is sufficient. I almost never introduce this pose to students over the age of 55. Our necks begin to lose their natural curvature as we age, making balancing on your head more risky. I offer Half Headstand instead.

Watch: How to User Your Breath to Lift Into Supported Headstand

Adapted from Yoga Myths: What You Need to Learn and Unlearn for a Safe and Healthy Yoga Practice by Judith Hanson Lasater © 2020 by Judith Lasater. Photos © 2020 by David Martinez. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc., Boulder, Colorado.