Guest commentary: A memorable visit with La Jolla scientist who helps kids with genetic disorders

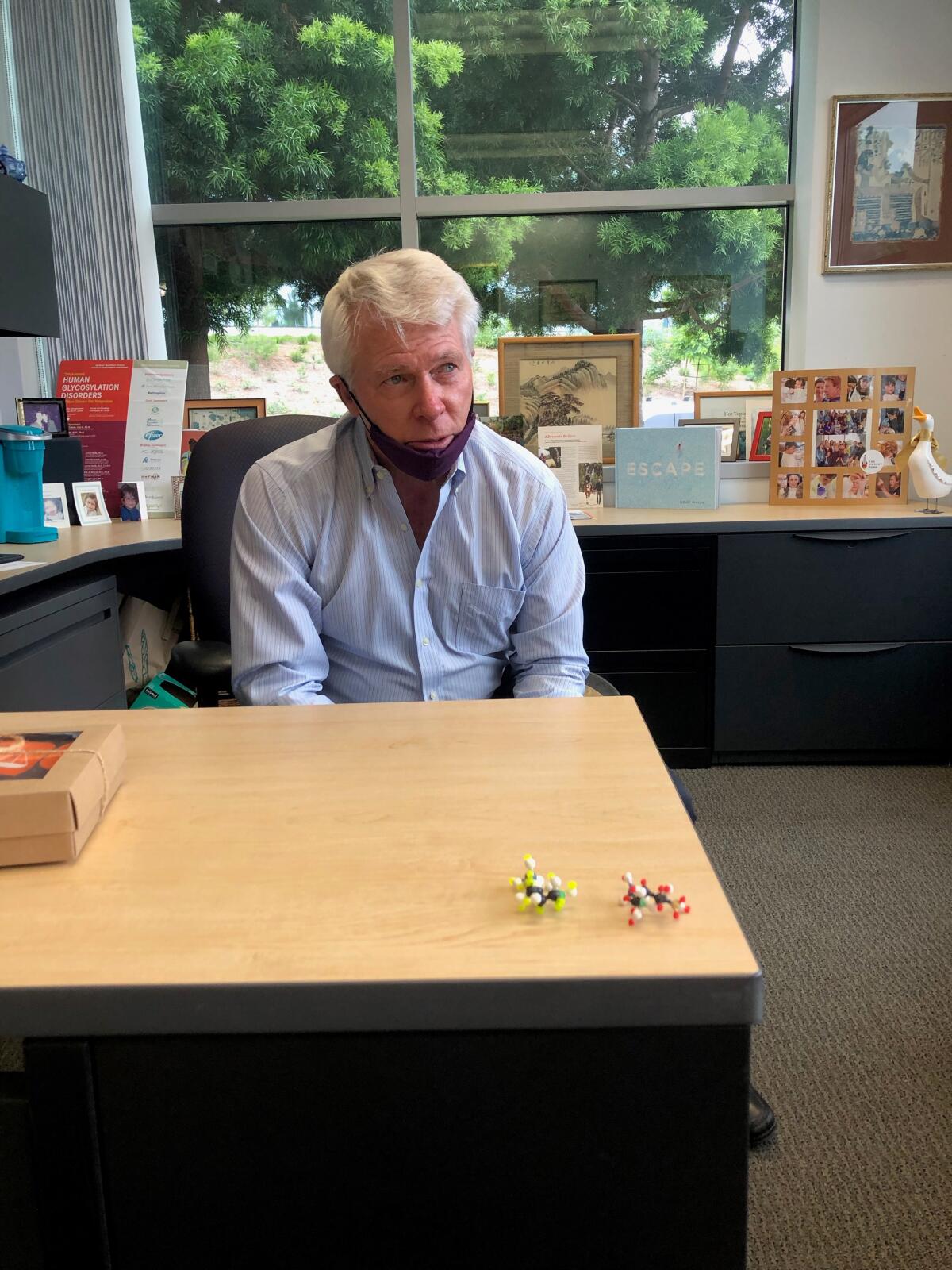

Hudson Freeze is a remarkable man. In late July, I had the pleasure of meeting him and touring his laboratory at the Sanford Children’s Health Research Center at Sanford Burnham Prebys in La Jolla.

Freeze is a scientist who specializes in glycosylation. You may ask yourself, what in the world is glycosylation? Well, it’s a process cells use to add sugar chains to proteins. Every person has an entire cell surface that is coated with complicated sugars called glycans. DNA gives cells instructions on how to make glycans. Sometimes the DNA makes mistakes and that causes a genetic glycosylation disorder. Sometimes those disorders lead to death.

Freeze cannot rewrite DNA’s mistakes, but he is finding treatments for some glycosylation disorders. He and his laboratory have helped more than 300 kids.

Freeze began his life in the small town of Garrett, Ind., whose population is approximately 6,000. He always was into science because of his childhood science teacher, who was such a good educator that every year his school would win the county science fair. Freeze’s sister was disabled and he wanted to help people like her overcome their illnesses.

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.

In summer 1966, Thomas Brock, a professor of microbiology at Indiana University, invited Freeze, his 20-year-old honor student, to join him in Yellowstone National Park to study thermophiles, bacteria that live in hot springs. When Freeze and Brock returned to Indiana in the fall, they agreed that Freeze would work on the thermophile he discovered in Yellowstone. Maybe he could even culture it in the Indiana laboratory.

When Freeze succeeded, he called it “YT-1,” for Yellowstone Thermophile 1. It turned out to be a special kind of bacteria — other scientists could use it to discover DNA’s disease-causing mistakes and help save kids’ lives.

“I work on diseases which are usually inherited through generations and I try to understand what is the cause of those diseases,” Freeze said. “It usually has a genetic basis, and then I see what I can do to come up with a treatment.

“None of this would have been possible if we didn’t go to the spring in Yellowstone first.”

For this discovery, Brock and Freeze were awarded the 2013 Golden Goose Award in Washington, D.C.

Freeze shared with me that much of his work was possible through the Rocket Fund, which started because of a boy named Rocket who had a rare disease that Freeze works on. Rocket’s grandmother visited Freeze’s laboratory and asked how she could help cure Rocket.

Freeze responded, “I’m sorry ma’am, we don’t have a cure; we don’t have enough funding to even start to help your grandchild.”

Rocket’s grandmother asked how much would it cost to get started, and Freeze said about $100,000. Rocket’s grandmother pulled out her checkbook and wrote Freeze a check for $100,000. With the funding, Freeze tried to discover a treatment for Rocket.

Unfortunately, Rocket died before Freeze could find a treatment. Freeze traveled to Rocket’s funeral in Los Angeles. Afterward, Freeze asked Rocket’s father if he could have something to remember Rocket by. Rocket’s dad grabbed the picture of him they had at the funeral and gave it to Freeze. To this day, Freeze has that picture in his office to remind him of Rocket and the important work his laboratory does every day.

The Rocket Fund continues to support Freeze’s lab, and because of that, the lab is able to help many more children. When I asked Freeze, “Is your job emotional?” he responded: “Very. It is so hard to watch these children have a problem that they can’t control.”

Today, Freeze gets his funding from the National Institutes of Health, private foundations and, of course, the Rocket Fund.

Freeze has done so much in his life. For example, he is an avid folk guitar player. He also threw the first pitch at a Padres game in Petco Park.

He has a great sense of humor. If he weren’t a scientist, I think he would be a comedian.

Visiting his laboratory was a highlight of my summer. For more information about the lab, visit sbpdiscovery.org.

Jacob Cooper is a sixth-grader at Gillispie School and lives in La Jolla. ◆

Get the La Jolla Light weekly in your inbox

News, features and sports about La Jolla, every Thursday for free

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the La Jolla Light.