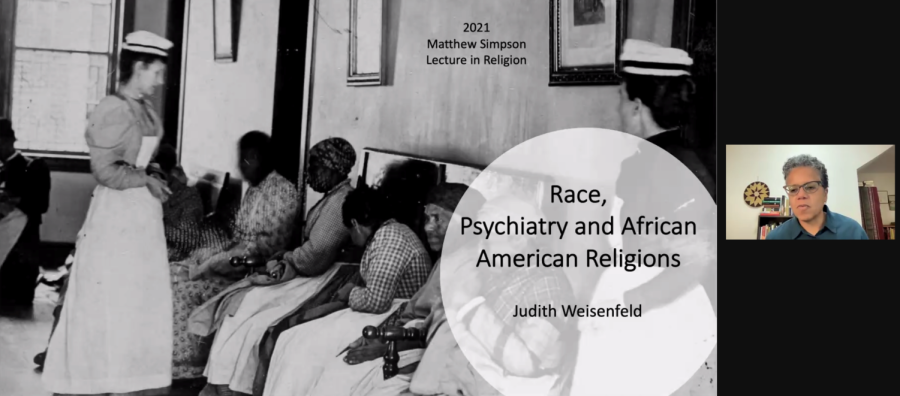

Judith Weisenfeld leads Matthew Simpson Lecture

Dr. Judith Weisenfeld, an Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University, spoke over Zoom on Sept. 30. Dr. Judith Weisenfeld, an Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University, spoke over Zoom on Sept. 30.

October 3, 2021

This year’s Matthew Simpson Lecture gave the audience a preview of her new research on psychiatry, race and Black religions in the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Dr. Judith Weisenfeld, an Agate Brown and George L. Collord Professor of Religion at Princeton University, spoke over Zoom on Sept. 30. Weisenfeld’s speech was titled “Spiritual Madness: Race, Psychiatry, and African American Religions.” Her current project, she said, is about understanding white America’s perceptions of African American religion, particularly relating to mental health.

Weisenfeld began with a story about George Pinkney, a Black man who was admitted to the psychiatric hospital due to “religious excitement.”

“George was finally admitted to the asylum in Sept. 1885, just six months after this new and large facility had opened and two months after the court had declared him a lunatic, again in the legal language,” Weisenfeld said.

Weisenfeld showed a chart titled “Percentage of Admissions Listing Religious Excitement as the Supposed Cause of Insanity in Virginia Hospitals in Selected Years (1883-1910),” which showed a significantly higher number of Black patients in this category.

“Focusing on the racialization of conceptions of mental normalcy in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and considering how white psychiatrist understandings of Black religions contributed to racialized theories that in turn shaped practices of treatment and often discipline for patients like George,” Weisenfeld said, “I show in the project how ideas about Black religions were central to emerging American psychiatric perspectives on race and mental illness.”

Weisenfeld gave many examples of Black patients and how the factor that precipitated their mental illness included a moral cause of religious excitement.

“In Babcock’s survey of reports from various state hospitals, he found that in a notable percentage of cases, he found that religious excitement was listed as the cause of insanity for these Black patients,” Weisenfeld said.

Towards the end of Weisenfeld’s lecture, she mentioned Constantine Clinton Barnett, who was a Black physician, and that she is interested in continuing her research.

“I’m interested in trying to find out more about him and other Black doctors in this period,” Weisenfeld said.

Although Weisenfeld is interested in continuing her research, finding archives in this area is getting challenging.

“It is very difficult now and becoming increasingly difficult to get access to these kinds of files. Some of the places I have been to have closed them off,” Weisenfeld said.

Weisenfeld is the author of Hollywood Be Thy Name: African American Religion in American Film, 1929-1949 and African American Women and Christian Activism: New York’s Black YWCA, 1905-1945. Her most recent book is New World A-Coming: Black Religion and Racial Identity during the Great Migration, which was awarded the 2017 Albert J. Raboteau Prize for the Best Book in Africana Religions.

Weisenfeld is also the co-director of The Crossroads Project: Black Religious Histories, Cultures, and Communities; it aims to increase public understanding of and engagement with Black religious histories and cultures.