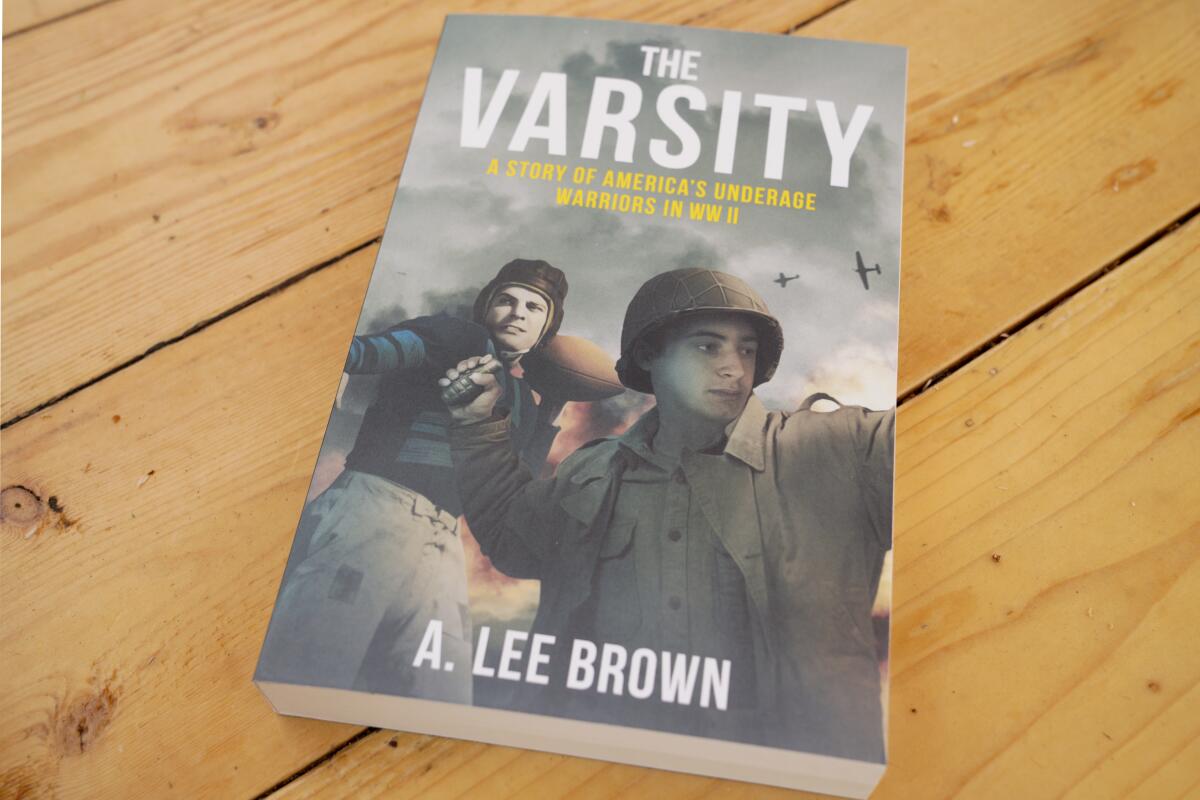

Ocean Beach author A. Lee Brown tells the untold story of underage WWII veterans in ‘The Varsity’

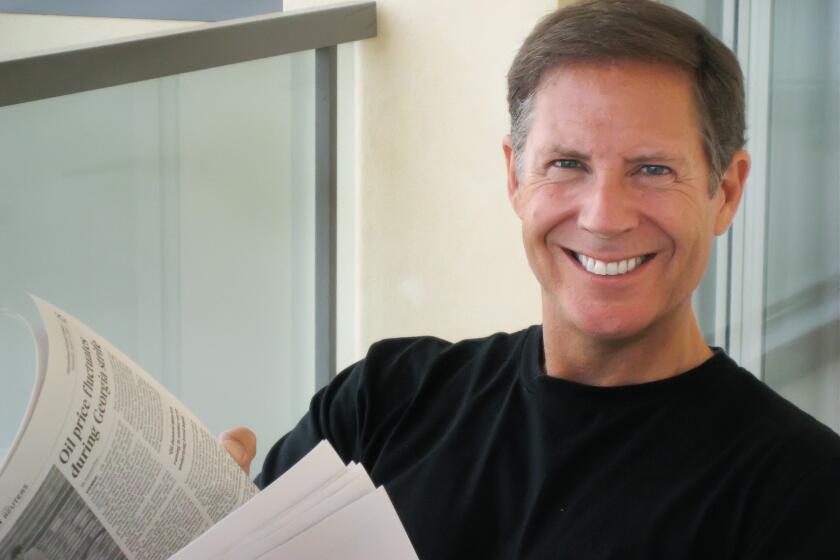

A. Lee Brown is not like most octogenarians. Most people his age would be content to enjoy retirement, but the longtime Ocean Beach resident displays a noticeable drive when it comes to a certain project.

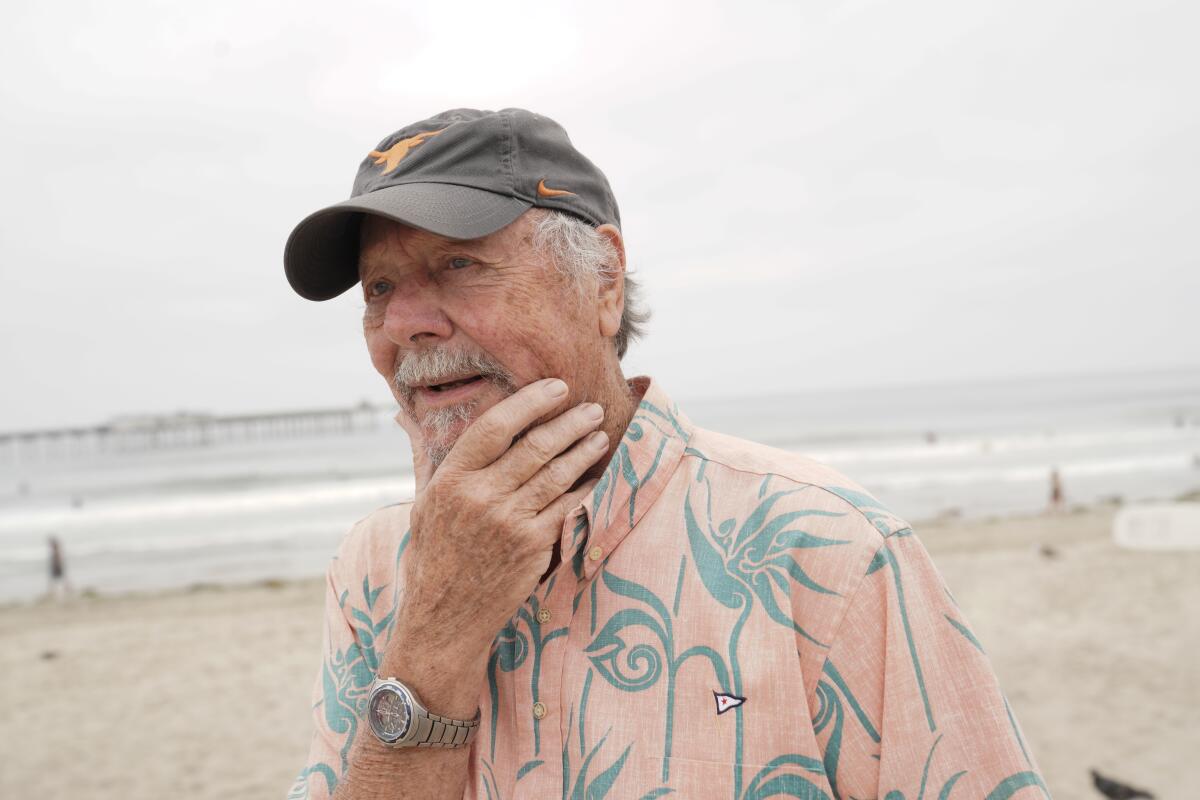

“I look back on it, and I might have went into it a little naive,” says Brown as he gazes over at the iconic Ocean Beach lifeguard tower where he once worked over half a century earlier.

That project is “The Varsity: A Story of America’s Underage Warriors in WWII,” a novel that, in more ways than one, has been decades in the making. Set both in San Diego and among the treacherous battles of World War II, the novel centers on two young men, boys at the time that they enlist, who return from the war and return to high school in Point Loma. Once there, they lead the school’s football team to a winning streak while also dealing with their own personal traumas from the war.

As is often the case with historical novels, the true stories that informed “The Varsity” are often stranger than fiction. For Brown, it began with an incidental conversation he had with a fellow surfer back in 1985. Brown had helped to organize a reunion of a surfing club that he joined in the 1950s while attending Point Loma High School. When a fellow member mentioned Point Loma High’s championship football team of 1945 and 1946, Brown inquired further and says he was surprised by what he was told.

“We were comparing old football stories, and he told me that many of these guys on the football team had enlisted in the military illegally, underage, went and fought in World War II and came home still in their teens.”

And while it seems far-fetched and highly problematic that minors fought in one of the most consequential conflicts of the 20th century, Lee couldn’t help but wonder: Was this something that happened a lot, or were these local boys something of an anomaly?

“I literally woke up one night and said to myself, ‘Jesus, I wonder if that’s true or not,’” Brown recalls. “And if it is true, why have we not heard about this? How many of them are there? I couldn’t find any information about it, and this is where the story really begins.”

‘A deliberately kept secret’

Finding information about military operations is already tricky enough, but for Lee Brown, the thought that children, some as young as 12, had faked their age or forged their parents’ consent in order to enlist and fight in World War II became something of an obsession.

At a table at an Ocean Beach cafe, Brown begins to pull out dozens of newspaper clippings and photographs he’s collected over the years. There’s the story of Army Lt. Audie Murphy, one of the most decorated soldiers who served in World War II, and who tried three times to join up at age 16 and was finally successful at age 17.

There’s the story of Calvin Graham, who was 12 when he joined the Navy shortly after the attack on Peal Harbor and was aboard the battleship South Dakota when it was bombed during the battle of Guadalcanal in 1942. Despite his body being torn up by shrapnel and falling three decks, Graham rescued a number of his shipmates and was awarded the Bronze Star and the Purple Heart.

But the truly touching and dispiriting clippings are the countless stories of soldiers who enlisted underage, served honorably, became heroes in some cases, only to return home and later be denied military benefits after their true age was discovered. In the case of Graham, when his true age was found out, he was sent to the brig, stripped of his medals and benefits, and was relieved of service. Some of his medals would be reinstated by the Navy in 1978, but they did not give him back his Purple Heart and only paid him $337 in back pay.

When Brown first started researching these stories in the 1980s and ’90s, he says he was initially shocked that people weren’t more aware of these underage veterans. But as he continued to dive in, it became more obvious why these stories remained secret. Sure, the military would likely not want the public to know that it had minors serving, but what surprised Brown even more was that many of these men often did not want to come forward.

“A lot of it was deliberate,” Brown says. “There were maybe up to 100,000 of these kids, some as young as 12, and they had violated federal law, and they were prosecuted if they were caught.”

“They just were reluctant to tell anyone, even their families,” Brown continues. “It was a deliberately kept secret by all parties.”

Things changed when Brown met Ray Jackson around the mid-2000s. Jackson, who joined the Marines when he was 16, founded the group Veterans of Underage Military Service in 1991 and had compiled a three-volume set of books (“America’s Youngest Warriors”) that became the authoritative compilation of the men and women who had served underage.

In April 2010, with some insistence from Jackson, Brown attended a Veterans of Underage Military reunion. He recalls hundreds of men in attendance and, with Jackson vouching for him, he began to make connections that he would use to schedule hundreds of interviews over the next three years.

“They knew I wouldn’t screw them and that they were safe,” Brown recalls.

Having interviewed dozens of veterans at this point, Brown initially thought about doing something in the non-fiction realm, but given the fact that Jackson had already written a comprehensive compendium, Brown decided relatively early on that he’d adapt the stories to a fictionalized form.

“At some point, I thought to myself: ‘Why don’t you try telling this story? To make it as historically accurate as you can, but do the old Samuel Taylor Coleridge business where you suspend disbelief?’”

‘A challenge to myself’

“I must have written that opening paragraph 100 times,” Lee says laughing while reading the first passage from “The Varsity.” “It took me almost half a year just for that paragraph.”

Still, within that half a year, and beyond, Brown kept plugging away at the rest of his novel. The fact that the novel opens at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery, at the funeral of one of the story’s protagonists, is not coincidental. Brown had attempted and reattempted to write “The Varsity” for years, but just like any first-time author, he became bogged down in the details.

One day, however, Brown made a trip out to Fort Rosecrans to take in the “headstones against the panorama of the Pacific Ocean,” and thought to himself, “this story needs to be told.”

“In many ways, it was a challenge to myself. I’d never written fiction or dialogue before,” Brown recalls.

The dialogue presented a certain challenge to Brown for sure, but even more daunting was presenting a novel that was both entertaining to the reader as well as historically accurate.

“I didn’t want to write anything that could be researched and found to be untrue,” says Brown, who spent days and weeks doing research at the Army Museum in Washington, D.C., and at the National Museum of the Marine Corps in Virginia.

The regiments that the novel’s protagonists, Bruce and Manny, serve in in “The Varsity” were actual units that served in World War II, and every battle and movement those units make in the book is historically accurate.

“There is some poetic license, of course,” says Brown, who adds that there are some autobiographical elements to the character of Bruce.

Using the story of the Point Loma football team as a template, “The Varsity” follows Bruce Harrison and Manny da Silva, two San Diego kids who enlist and serve illegally, then come back home in hopes of finishing high school. The two end up joining the varsity football team and, serving as co-captains, help to turn a feckless squad into a championship contender.

“We now estimate that about 30,000 soldiers returned to their high schools nationwide,” Brown says. “Given the banality of senior ditch days and homecoming parades for guys who’s fought in a war, many of them turned to sports.”

It’s understandable that many of these men, boys rather, had picked up certain skills while in the military, likely making them much more adept to the physical strenuousness of high school athletics. When it comes to football in particular, a so-called killer instinct might come natural to someone who might have literally had that instinct tested.

“Hell, some might have killed people,” Brown says. “It’s a sad fact, but it’s true.”

‘A Homeric journey’

Brown often likes to describe “The Varsity” as a “standard Homeric journey,” referring to Homer’s classic tale of Odysseus returning home to the island of Ithaca after fighting in the war at Troy. But Brown’s nearly 40-year journey to write his first novel could be seen as something of an odyssey itself.

And even without his new career as a novelist, Brown has lived a distinguished life. Born in Texas, he moved to Ocean Beach when he was very young and says he got “hooked on the beach.” He attended San Diego State University and, after some sojourns in Minnesota and Texas, where he received a water sciences doctorate from the University of Texas, he moved back to San Diego to teach at SDSU and Grossmont College. After receiving multiple educator awards, a deanship and penning numerous textbooks and scientific papers, Brown retired from the California State University system in 2018 after 25 years. That same year, he was diagnosed with multiple myeloma, a cancer of the plasma cells. He’s now in remission and says he feels good.

However dire, Brown’s diagnosis did serve as one final push to complete “The Varsity” and get it out into the world.

“I almost had to unteach myself the academic writing, but in many ways, the story just told itself,” says Brown, who often read Hemingway for inspiration.

And while he’s already busy penning a semi-autobiographical novel about San Diego beach culture in the 1960s, Brown is, for the moment, simply enjoying some of the positive reception he’s received for “The Varsity” since self-publishing it last year. He pulls out a handwritten letter from former newscaster and author Tom Brokaw, who ended up writing a glowing blurb for the book. The messages that mean the most to Brown, however, remain the comments and letters he receives from surviving underage veterans and their families.

“A lot of people who did serve during that time would ask, ‘How did you do that? Were you there?’ ” says Brown, who was made an honorary member of Veterans of Underage Military Service. “Of course that feels good.”

“The Varsity: A Story of America’s Underage Warriors in WW II” by A. Lee Brown (Eight Bells Press, 2020; 384 pages)

Combs is a freelance writer.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.