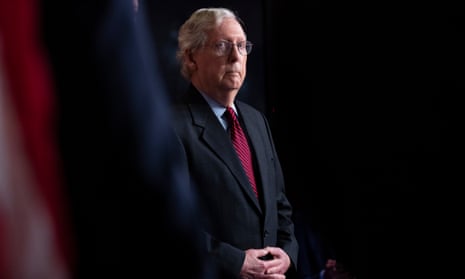

At the end of a week in which Mitch McConnell refused to rule out blocking a Joe Biden supreme court pick if Republicans take the Senate next year, an expert said the court may have reached a “turning point” regarding public perception of its politicisation and need for reform.

In an interview with Politico, the Senate minority leader was asked if he would “mount a blockade” should a vacancy arise with Republicans holding the Senate and Democrats the White House.

McConnell famously did just that in 2016, when he denied a hearing to Merrick Garland, Barack Obama’s pick to replace the late conservative justice Antonin Scalia. That held open a seat eventually filled by Neil Gorsuch, the first of three conservatives installed under Donald Trump.

“Cross those bridges when I get there, we are focusing on 22,” McConnell told Politico, referring to the midterm elections in a variation on a theme with which he has already infuriated liberals, saying it was “highly unlikely” he would let Biden confirm a justice in 2024, the year of the next presidential contest.

“I don’t rule anything in or out about how to handle nominations if I’m in the majority position,” McConnell said.

The Kentucky senator was in the majority position in September 2020, when Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, a liberal lion, died less than two months before a presidential election.

Ignoring his claim in the case of Garland that no justice should be installed in an election year, McConnell oversaw the swift confirmation of Amy Coney Barrett on a 52-48 vote, the first in modern times with no support from the minority party.

That split the court 6-3 in favour of conservatives. Public approval of the court has since dipped, polling shows, particularly after cases like one from Texas this month in which the court refused to block a ban on abortions early in pregnancy and provisions to allow private citizens to benefit financially from suing anyone involved.

That majority was made up of the three Trump justices and two other conservatives, with the three liberals and Chief Justice John Roberts, who was appointed by a Republican, George W Bush, in dissent.

Major decisions on immigration and evictions have also gone conservatives’ way. Abortion, gun and religious rights are all on the docket. To many, the court faces the most serious threat to its legitimacy since its decision settled the 2000 presidential election in Bush’s favour.

“I think we may have come to a turning point,” Irv Gornstein, executive director of Georgetown University’s Supreme Court Institute, told the Associated Press.

“If within a span of a few terms we see sweeping right-side decisions over left-side dissents on every one of the most politically divisive issues of our time – voting, guns, abortion, religion, affirmative action – perception of the court may be permanently altered.”

Paul Smith, a lawyer who has argued before the court in support of LGBTQ+ and voting rights and other issues, told the AP people were increasingly upset that the “court is way to the right of the American people on a lot of issues”.

But proposals for reform, perhaps by adding justices to a panel not constitutionally bound to be nine-strong, are reliably controversial. Some experts against structural reform argue that views of the court have dipped and rebounded before.

Roman Martinez, a lawyer who regularly argues before the court, told the AP “a sustained campaign to delegitimise the court … has gotten some traction on the left”.

Tom Goldstein, founder of the Scotusblog website who argues before the court, said the court “has built up an enormous font of public respect, no matter what it does”.

But the justices are evidently aware of a problem at least of public perception. Three – Barrett and Clarence Thomas from the right, Stephen Breyer from the left – have recently claimed not to rule according to political beliefs.

Breyer, at 83 the oldest member of the court, is the subject of calls to retire so Biden can confirm a replacement while Democrats hold the Senate. Breyer has said he does not intend to die on the court, as Ginsburg did, but has refused to be drawn on when he might step down.

In Louisville, Kentucky, meanwhile, Barrett recently told an audience: “My goal today is to convince you that this court is not comprised of a bunch of partisan hacks.”

She was speaking next to McConnell, at a center named in his honour.