“I really felt like I was running,” Rep. Cori Bush says. She’s speaking to me from her home in St. Louis, long braids coiling down past her shoulders, her signature thick lashes framing her eyes as they widen while she sets the scene. She’s describing the moment this past summer when, as a sitting member of Congress, she decided to sleep on the steps of the U.S. Capitol. The House had just gone on recess despite the looming July 31 deadline of the eviction moratorium that had been put in place to help the estimated 11 million households that have been unable to make rent due to the pandemic. Legislators were leaving the Capitol, and the administration hadn’t signaled if it would extend the moratorium. Right-wing pundits were arguing that the moratorium itself was unconstitutional; social media and news broadcasts were flooded with accounts from supposed landlords who were spreading disinformation about the moratorium. If you were going off the odds of how things usually go in Washington, it seemed unlikely that anything would change. “I felt like I was running on the inside of myself,” Bush says. “It was just … go.”

A first-term congresswoman representing St. Louis and part of its greater metropolitan area, Bush had already made a name for herself in national politics with her skill for breaking down topics and issues often framed as contentious or complicated in clear, moral terms. She’s a natural communicator, in the vein of great orators like Fannie Lou Hamer and Shirley Chisholm. Her voice is deep and sweet, with the musical swagger of the Black Midwest, a Joshua’s trumpet of an instrument that, when you’re listening to her wield it, feels as if it could cause walls to tumble down. Her flair and style (more on that later) and adeptness at social media mark her a clear member of the Squad—that group of progressive Democratic members of Congress that includes Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, Ayanna Pressley, Ilhan Omar, Rashida Tlaib, and Jamaal Bowman. But on July 30, the night she began her protest, many of her allies were gone, having left Washington for summer break. The national media was running stories on the end of the moratorium as if it were a done deal; within a day, attention was destined to move elsewhere.

“My original thought was to do a sit-in on the floor,” she says, “but they were literally closing the doors. Nobody could get in. Eventually, it was just Alex [Ocasio-Cortez] and I, in the parking lot, outraged. She said, ‘Let’s just do an Instagram Live.’ Once we finished that, though, it felt like I couldn’t let it go. I’ve got to do something with this energy.”

For Bush, the urgency came in part from personal experience. She has been evicted three times in her life—the first, after a domestic-violence incident; later, as a young mother recovering from back-to-back pregnancies; and most recently in 2015, after she became active in the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, instigated by the police killing of Michael Brown. Bush has said in the past that she believes this eviction was politically motivated, that neighbors worried she would bring trouble to the block.

That summer evening at the Capitol, though, “I turned to my chief of staff and I said, ‘Let’s just sleep out here. That’s what will be happening to the people affected,’” Bush says. “If I was home in St. Louis, I would have had the sleeping bags, the tents and chairs, all this stuff you need when you’re going to occupy space. In D.C., I didn’t have even a lawn chair. I said to my staff, ‘Let’s change clothes into something warm just in case it gets cold tonight.’ But that was it. We didn’t even have water.”

Her staff made a Target run. Media attention immediately followed. It seemed everyone—from housing activists to centrist pundits to left-wing influencers—had an opinion, with most of them agreeing, for every reason up and down the political spectrum, that Bush’s protest wouldn’t work.

But almost miraculously, for a brief moment, it appeared to do so. Bush stayed on the Capitol steps for five days and four nights, while other legislators, including House speaker Nancy Pelosi, pressured the Biden administration to extend the eviction moratorium. On the fifth day of Bush’s protest, August 3, a new 60-day moratorium was announced. And almost just as suddenly, the grace broke. Late on the evening of August 26, the Supreme Court delivered an unsigned opinion vacating the moratorium.

It’s an example of the sudden reversals in policy and action in American politics at this moment. What is the American project in this third decade of the millennium? Are we a nation that measures its success on how well the government aids and protects the most vulnerable, or is the thing that makes America great how strongly our systems protect those in power?

For Bush, the answer is clear. “We are in an unprecedented and ongoing crisis that demands compassionate solutions,” she says the morning after the SCOTUS decision. “We already know who is going to bear the brunt of this disastrous decision: Black and brown communities. We didn’t sleep on those steps just to give up now.” Legislative politics is a domain marked by painstakingly slow negotiations and choreographed rituals of agreement and debate. Bush moves at a different pace.

It would be a mistake, though, to read Bush’s method as reckless or haphazard. At one point she tells me, “I’m not someone who’s seasoned in electoral politics, as far as holding office.” Her reluctance to claim that space is perhaps because she grew up so close to it. Her father held a number of political offices throughout her childhood.

“We started out on a street in St. Louis that’s so notorious, it’s not even there anymore,” she says. The cul-de-sac that residents called “the Horseshoe” had a crime rate so high, the city of St. Louis took over, tore down all the homes, and filled in the entire space with grass.

Her family left when she was still young, settling in suburban Northwoods, a predominantly white community at the time, though Bush remembers their street having numerous Black families. Her father, Errol Bush, was able to build a middle-class life for his family; he worked as a meatcutter at a local supermarket, at a wage that allowed him to buy his home—where he still lives—and send his children to private schools. In 1984, he joined Jesse Jackson’s campaign for the Democratic presidential nomination. Encouraged by what he experienced with the Rainbow Coalition, he entered local politics. He started out as president of Cori’s private Catholic school’s PTA and worked his way up to mayor. Currently, he’s an alderman for the city.

“I was one of his campaign workers,” Rep. Bush says. “I would knock on doors. I would answer calls. By the time I was 16, I had worked every part of a campaign.”

“I took Cori with me because people were more likely to open the door to a cute little girl,” Errol Bush explains. “She’d say, ‘Open up. My daddy wants to talk to you.’”

His daughter says, “I saw my dad give so much. I saw the corruption and the grief that would just come at him, all the lies and the negativity. Why would somebody volunteer for this?”

She was certain she would never be a politician. And then came Ferguson.

When the Ferguson uprising began in 2014, Bush was 38 years old, the single mother of a son and a daughter who had worked hard to improve her family’s life by entering nursing school in her late 20s and working her way into a higher paying job.

Both her grandmothers were nurses; they wore their “whites,” as she explains it. She volunteered as a candy striper in high school, but life took over and she found herself working in a day-care center, eventually with two kids to support. A stellar employee, she was regularly promoted, until one day her boss explained she had reached the salary cap. No matter how hard she worked, she would never make more than $10.50 an hour. Recognizing Bush’s potential, her boss encouraged her to apply to nursing school. “Usually, it takes a few years to get in. I applied in June and was accepted for that fall,” says Bush.

“Once I graduated and became a nurse, life changed. My next job, I was making $19.50 an hour. Within one year I was promoted, and I went to making $32.81, or something like that, an hour. And having health insurance that didn’t cost me a lot. Health insurance, I think, was $121 for me and my two kids.”

The sums of money Bush describes are both life-changing and not that much in the understanding of household budgets most politicians talk about. It’s a trajectory that serves as a microcosm of life in post-civil-rights America—the promise of upward class mobility, allegedly now open to all, but also the precarious stakes most people have in maintaining a life in the middle class. In the 1980s, Errol Bush could buy a home and pay for an education for his children on a meatcutter’s salary. A generation later, Cori Bush worked a similar middle-class job, as a day-care provider, but found only precarity and housing instability. Ferguson, momentarily, felt like a disruption of all of those narratives—that to make communities safer, you should spend most of your budget on police; that the United States was headed toward a post-racial future; that Americans didn’t need to protest in the street for anything anymore. Bush, with her training as a nurse, quickly volunteered to be a street medic.

“During Ferguson,” her father tells me, “I turned on the news and this whole block was burning. Suddenly there was a flash across the screen and it was Cori. She was out there in front of the tanks and the fire trucks. I couldn’t believe it. I tried to call her, but she wasn’t picking up her phone. I tried to go down there, but everything was blocked off. All I could do was pray for her.” He knew, in that moment, a deep reckoning was upon his family.

Her leadership skills were evident from the start. As the uprising came to a close, a fellow organizer, Muhiyidin Moye, who has since been murdered, asked her to consider running for one of Missouri’s U.S. Senate seats. She remembers him saying, “You have a voice. You need to run.”

She turned him down, but he kept asking. As she spoke to him, she remembered what she had seen during the uprising. During a protest, marching with her son, she lost track of him in the crowds. “I just thought, He could be another hashtag,” she said. “I thought, What are you doing to make his world better? The more I said no, the more this yes rose up inside of me.”

She ended up running for office three times, finally narrowly winning the Democratic primary in Missouri’s First District in August 2020 (and winning the general in November). She was up against an incumbent, Rep. William Lacy Clay Jr., whose family had held the seat since 1969, when his father took office. Supported by newly powerful progressive organizations like the Justice Democrats, Bush’s campaign picked up endorsements from political superstars like Bernie Sanders.

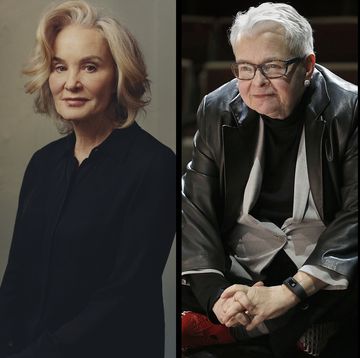

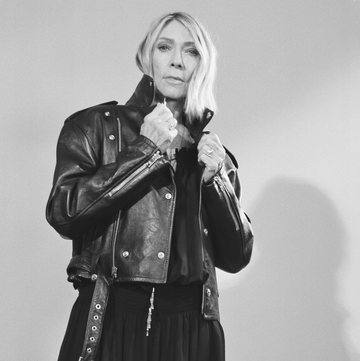

Because of her rising profile, Bush was subject to increasing attacks. She spoke about it often, noting on Twitter, “People have commented on everything from my clothing, to my hair, to my hips, to my AAVE. I am a Black woman and I am proud of it. I am the people I serve, and I’m bringing that to Congress.” Throughout the general election, she posted videos of herself in the clothes she proudly wore: formfitting dresses, leggings, and tall boots. Her father tells me that people in the neighborhood now regularly drop off dresses, jewelry, and shoes for her to wear in Washington. “They say, ‘We want her to look her best. She’s representing us.’”

But the attacks against her have been more substantive as well, most notably on her unequivocal stance to defund police departments, even as she represents the city that has the highest murder rate in the country—and the highest rate of police killings. Of this, she says, “Defunding the police means that rather than investing more money in militarized policing, we invest in the policies and programs that meet people’s needs and make communities safe: guaranteed housing, health care, quality education, livable wages, and good jobs. It does not mean that when you call for help, no one will be there to respond. It means making sure that the right professionals are responding to the right calls. I will do everything in my power to create communities that are safe for everyone. It’s our obligation as lawmakers to do the work that saves lives—no matter how challenging that work might be.” Her stance has led to criticism that she’s hurting the prospects of Democrats in swing districts. In response, Bush says, “Let’s come up with another way to make sure that we get them elected. Don’t ask me to tone it down, because toning it down has been what has allowed us to be where we are right now.”

Right now, of course, is the political landscape Bush walked into in 2021. In January, her term began with the attempted coup by right-wing extremist supporters of President Trump on January 6. Bush herself introduced a resolution to expel those Republican members of Congress who sought to overturn the election and helped incite the attack. It is a moment of profound disunity that some, including President Biden, argue can be healed by active bipartisanship.

Bush counters, “I am a product of middle-ground policy,” she says. And she believes it has failed her. “The fact that I lived low-wage [jobs] for so many years, that my credit was so messed up because of the poverty that I was living through, even though I was faithful to my job for 10 years. What that does to you physically, living in places that were unsafe,” she lists out. “I’m a product of people not focusing on what mass incarceration has done to our communities. My friends dying—my friends who are now in prison, year after year.”

She tells me about the Delmar Divide, a street in her district where one can literally trace the economic and racial fault lines built into our country’s policies. “As you go south of that street, there’s an 18-year difference in life span. And the median income goes up by about $40,000, just by crossing the street,” she says. “A lot of the investment is in those communities. And then there’s the disinvestment on the north side of that street. There are parts of my district that look like there was a war: big, huge, old cathedrals with the roof gone; schools abandoned for so long that they need to be torn down.” She tells me that despite the overwhelming poverty in her district, there’s one person there who owns 1,700 “broken-down and dilapidated homes.”

As a result, she says, she can’t join the call for always seeking the middle ground: “It’s that failed policy that allows St. Louis to be where we are right now.” Working to try to change such big structural issues can feel hopeless, especially when victories, like the one Bush scored in August, can be wiped out by stacked courts. But Bush and her allies don’t see it that way. Senator Elizabeth Warren, who worked with Bush on the moratorium, says, “In a legislature, there’s a lot of negotiation that takes place out of view of the public. But every once in a while, one person stands up and says from the heart, ‘I’m in this fight because it is the right fight. And I will stay here until we make change.’ That’s what Cori did.”

Bush says, “If I’m not on the inside, if nobody wants to fight, if nobody’s in there to push that agenda, then how do you get it on the outside?”

Fashion Editor: Miguel Enamorado; Hair: Anaston Richardson; Makeup: D. “Carta” Davis.