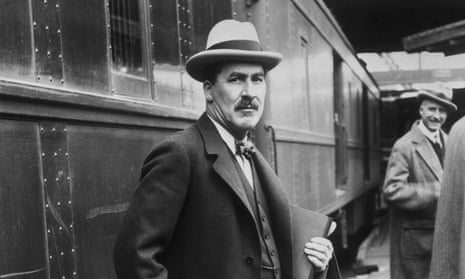

The audience that filled the New Oxford theatre this afternoon, when for the first time London, Mr Howard Carter told the story the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamen represented all the classes of the community who have been thrilled as they watched the progress of his work. Members of scientific societies, representatives of the museums, personal friends of Lord and Lady Carnarvon, travellers who knew Egypt well, and people whose minds had been only recently opened to the wonders of ancient Egypt – all listened for two hours to the wonderful story.

General Sir John Maxwell, who presided, said Lord Carnarvon once told him he had had many thrills at the first opening of the tomb, but perhaps the greatest thrill of all was when he was able to look into the blue faience sarcophagus in which the body of the Pharaoh rested.

Mr Carter, who is an excellent lecturer, briefly summarised the conclusions drawn from the discoveries. Then a series of pictures were shown of the Valley of the Kings, the stages of the work of excavation, the discoveries of the ante-chamber, and the many treasures, some of these shown from several points of view so that the detail of their marvellous workmanship might be appreciated. Then came kinematograph pictures showing the removal of the treasures, and at the end more photographs of the entrance to the actual burial-chamber.

An almost unknown king

“We were astonished,” he said, “by the productivity of the art which the tomb contained. Tutankhamen’s tastes might have been those of an average young Egyptian nobleman rather than of a royal prince. Domestic affection was suggested, rather than the religious austerity that characterised other tombs. We know very little of this shadowy king, who has been so much discussed. We do not know whether he was even of royal blood or where he came from, or why the heretic king chose him as a husband for his daughter. Perhaps he lived at Thebes so that the king should have a strong supporter there, and he was afterwards compelled to acknowledge the supremacy of Amen-Ra. It was by virtue of that acknowledgment that he was buried at Thebes.

“I have no shadow of doubt,” said Mr Carter, “that this is the tomb of Tutankhamen, but it is of semi-royal, semi-private-type – more the sepulchre of a potential heir than of a king”

The lecturer then showed some wonderful views of the Valley of the Kings, “this awe-inspiring valley, remote and solitary, whose strangely solemn and almost gloomy character was yet not unproductive of delights. Everything around was calm and motionless, as if prepared for eternal duration. The coloured doors of the Tombs of the Kings made a brilliant contrast to the rugged sunburnt rocks in which they were harboured.”

These doors, said Mr Carter, led to the wonders of long corridors adorned with pictures and sculptures, and at last to the great vaulted and pillared central burial-chamber. Since the year 1467 BC thirty kings had been buried in the Valley, and now probably only two remain. The audience applauded when Mr Carter added: “There, when the claims of science have been satisfied, we shall leave Tutankhamen lying”.

Step by step the audience followed the expedition’s work, the removal of enormous debris, the first indication of the existence of the door, the clearing of the steps and sloping corridor, and then the ante-chamber, with its first homely appearance of being a lumber-room. Two coloured photographs were shown, one of the coronation chair, glorious with gold and blue faience, and the other of the panel at the back of this chair, which Mr Carter described as the most beautiful tableau discovered in Egypt.

Colour alone could do justice to this scene of a richly decorated room in a palace. The sun shining through an opening in the roof, and in the foreground two appealing young figures – the King seated on a cushioned chair and his wife standing before him with one hand holding a box and the other putting oil or perfume on his shoulder. Another delightful picture from the side of a casket showed the king shooting ducks, while his charming girlish wife handed him an arrow and pointed to a fat duck.

Removing the treasures

The kinematograph pictures vividly impressed one with a sense of the enormous labour involved in moving the treasures. The door of the room was flooded with sunlight, and from the shadowy depths of the stairs workmen or, where the most precious articles were concerned, the members of the expedition, emerged bent beneath the weight of solid furniture or parts of the four chariots. We saw one side of the Hathor couch, heavy with gold, borne out into the sunshine, laid with reverent care in a huge tray which was lined with cotton wool and then borne on the shoulders of labourers and conveyed under military escort to the laboratory. A glimpse of the laboratory showed an expert at work on reconstruction of the jewelled collar whose threads had rotted in 3,000 years.

More thrilling than all that had gone before was Mr Carter’s description of the breathless moment when an opening was made through the door leading into the burial-chamber, and the party had their first view of the great gilt shrine which protected the royal sarcophagus. He described how, with Lord Carnarvon and the director of the Antiquity Department, he entered the chamber carrying a portable electric light and paying out the cord as they passed on. “Over the inner shrine there was a magnificent linen pall. We felt that we were in the presence of the King and that we must do him reverence.”

Then came the tremendous surprise of finding at the eastern end of the chamber a door leading to an inner chamber which had not been closed and sealed. “A single glance told us that within this little chamber lay the greatest treasures of the tomb.” It also contained the most beautiful casket Mr Carter had ever seen – a thing so lovely it brought a lump into his throat.

This is an edited extract

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion