Is the U.S. becoming more bike friendly?

In many cities, the pandemic has reinforced a trend: They're building out the infrastructure needed to make cycling safe.

If you’ve noticed more people biking in town over the last year or two, it’s not just in your head. Biking has exploded during the pandemic, with millions of Americans mounting bicycles for the first time in years. Is it the start of a long-term trend?

There are good reasons to hope so. Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse emissions in the U.S., and cars and light trucks account for 58 percent of transportation emissions. Switching from cars to bikes cuts emissions much faster than switching to electric cars.

And motor vehicle accidents still kill more than 39,000 Americans a year—including more than 700 cyclists.

Clearly the U.S. is not a bike-friendly country overall. Only one percent of all trips that Americans take—to work, to the store, on vacation—are by bike, compared with 87 percent by car or truck.

According to League of American Bicyclists (LAB), a nonprofit that collects data on biking in the U.S., the total number of bike rides Americans take each year had actually been falling in the years leading up to the pandemic. The number of people who ride their bikes to work fell from around 900,000 in 2014 to just over 800,000 in 2019—about .5 percent of all commuters.

“Commute to work rates have been down, bike fatalities have been up,” said Ken McLeod, policy director at the LAB.

Compare that to the Netherlands, say, where 27 percent of workers commute by bike. But Dutch cities didn’t used to be that bike friendly, said John Pucher, a professor emeritus of urban planning at Rutgers University who specializes in biking.

“Americans have this image, ‘Oh cycling is just paradise, and it’s always been paradise in Europe,’” Pucher told me when I interviewed him for Overheard, the National Geographic podcast. “Wrooong. Not true!”

If some European cities look heavenly to American cyclists today, he said, it’s because over the past few decades they’ve actively reclaimed space in the urban landscape from cars. And some American cities today have started on that same trend.

(Read about how Minneapolis is fostering a bicycling boom.)

Safety first

Some 70 percent of people surveyed in the 50 biggest metro regions in the U.S. say they’re interested in biking. Why don’t they bike more? It comes down to safety. Half of the people surveyed said they were, understandably, too afraid to bike on the street.

Bike safety isn't about painting bike lanes on every street, Pucher said. It’s about creating bike networks—webs of bike paths that can take you safely from point A to point B. Good bike networks are made of things like greenways (off-road paths that often run next to rivers and lakes, or along old railway corridors), protected bike lanes with physical barriers separating riders from cars, and quiet streets.

“Cycling has to become boring to become really successful,” said Ralph Buehler, chair of urban affairs and planning at Virginia Tech. “Putting a painted biking lane on a 40-mph road is not going to appeal” to the potential cyclist afraid of a close encounter with a car.

The good news is that bike networks were expanding in the U.S. even before the pandemic. Between 1991 and 2021, there was a six-fold increase in paved, off-road trails, from 5,904 miles to 39,329 miles, Pucher said. Washington D.C., Minneapolis, Chicago, and Los Angeles more than doubled their city bike lanes from 2000 to 2017, while New York and Seattle more than tripled theirs.

And the increase in protected bike lanes is even more dramatic: Their total length, nationwide, went from only 34 miles in 2006 to 425 miles in 2018. With the surge of activity in the pandemic, Pucher estimates that number is now well over 600 miles.

New York City alone already has 200 miles of protected bike lanes and plans to keep adding more at the rate of 50 miles a year. “They’re really pushing,” Buehler said.

In fact, most American cities are building more bike lanes. Cities in the West and East are leading the pack, but the trend is nationwide.

“It’s in the plan of every single city I’m aware of,” Pucher said. “I see this happening in Raleigh. Raleigh! If even North Carolina cities are gung-ho … I just see, in the coming years, a big expansion.”

City versus country

The national statistics showing a decline in bike ridership are a bit misleading, McLeod said. Biking infrastructure and ridership are indeed down in rural and suburban areas—but cities tell a different story, especially cities that have invested in their bike networks.

In Santa Cruz, California, about 9 percent of workers bike to work; in Boulder, Colorado, it’s just over 10 percent. In Davis, California, it’s 19 percent—an almost European level.

Bigger cities have seen big increases in ridership too. “D.C. has really had a dramatic change,” McLeod said.

In the late 1990s, only 1 percent of D.C. commuters traveled by bike. The city started building protected bike lanes in the early 2000s—and by 2018, the number of bike commuters had jumped to 5 percent.

By comparison, in the German city of Frankfurt in the late 1990s, 6 percent of workers were commuting by bike. That city too installed a bunch of bike infrastructure, and by 2018, its bike-commuter rate had reached 20 percent. Buehler, who worked on a study comparing the two cities, said that if D.C. stays the course, it’ll look like Frankfurt in another decade or two.

Other cities are evolving similarly, including Seattle (from 4,179 bike commuters in 1990 to 17,092 now), Chicago (3,307 to 20,268), San Francisco (3,634 to 20,268), and Portland (2,453 to 21,315).

The pandemic may have sped things up, according to an analysis done by Buehler and Pucher.

“In every single city we looked at, there has been an increase in cycling,” Pucher said.

During lockdowns, some cities installed temporary lanes as trial runs. Boston threw together a bike lane made of orange traffic cones on Boylston Street, a major thoroughfare. The city has since made the change permanent, trading the cones for bollards.

“That’s happened in New York, that’s happened in Seattle, it’s happened in Oakland,” Pucher said. “COVID demonstrated how many things can be done in even a very short period of time.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

Environment

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

- This ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrificeThis ancient society tried to stop El Niño—with child sacrifice

- U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?U.S. plans to clean its drinking water. What does that mean?

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

- The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’The real spies who inspired ‘The Ministry of Ungentlemanly Warfare’

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

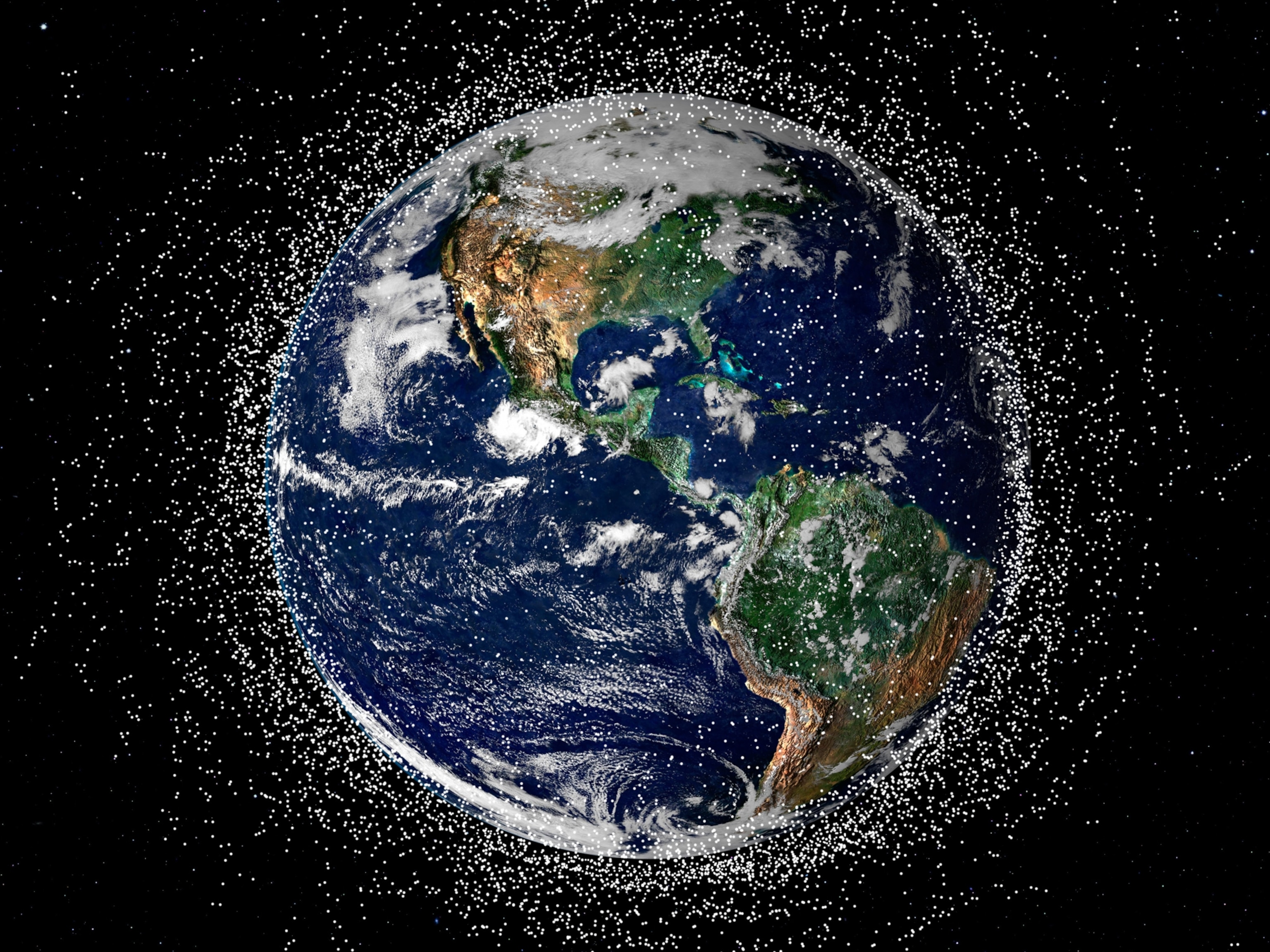

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

- Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?Can aspirin help protect against colorectal cancers?

Travel

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico

- Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?Is this small English town Yorkshire's culinary capital?

- This chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new directionThis chef is taking Indian cuisine in a bold new direction

- Follow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood ForestFollow in the footsteps of Robin Hood in Sherwood Forest