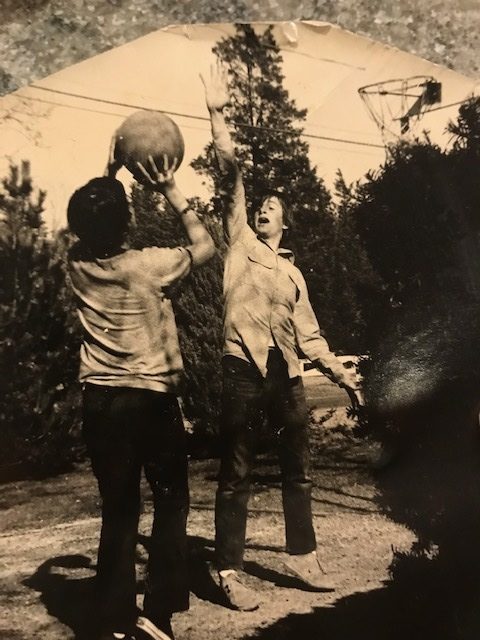

Gregg de Waal and I shuffled around his East Hampton basketball court, shooting jumpers while jumping through the hoops of “American Pie,” Don McLean’s magical musical mystery tour. Who, we wondered, is this singing jester who wears James Dean’s coat? Why does he steal a king’s thorny crown? What’s he doing in a cast on the sideline of a football field invaded by a falling fallout shelter.

Our guessing game was played around the globe in the fall of 1971, when “American Pie” became a sensational single and a more sensational puzzle. The game bonded me to Gregg, whose friendship eased me into my first and only year at East Hampton Middle School. As the seasons changed, as I changed from outsider to insider, I changed “American Pie” into my South Fork story. A half century later, it still kills me — softly, loudly, every which way.

There was no way “American Pie” wouldn’t become my anthem. I grew up in the Bronx suburb of New Rochelle, McLean’s hometown. As a youngster he delivered The Standard Star, the same newspaper that led me to become a newspaper writer. On February 4, 1959, when I was 10 months old, the paperboy read The Star’s front-page article about the plane-crash death of Buddy Holly, his idol. Holly’s zesty tunes — “Peggy Sue,” “That’ll Be the Day,” “Rave On” — had helped him hurdle major obstacles: severe asthma; a sister’s addictions; his father’s sudden death, which he watched and predicted. Eleven years later he began siphoning his sorrow into a song shrouded by “the day the music died.”

Holly died when McLean was 13. I was 13 when I first heard “American Pie.” My family had settled in our house in Wainscott, renting our New Rochelle home to save money and my parents’ troubled marriage. My mother and I were driving through Springs, scouting cheaper real estate, when the radio played a song seemingly beamed from another galaxy.

Everything about “American Pie” mesmerized. The snappy rhymes. The happy melody. The exotic settings. The cosmic images. The galloping pace that conjured mustangs and Mustangs.

That afternoon our Ford morphed into the narrator’s Chevy in 512 musical seconds. I felt like McLean must have felt when he discovered Holly’s voice. Reborn. Restrung. Retuned.

My horsepower passion was revved up by my basketball buddy, Gregg de Waal, an East Hampton native with a goofy grin, searchlight eyes and the quiet curiosity of a budding bayman. We made “American Pie” our research project, dissecting countless stories and theories as we decoded the 8-minute-plus, two-sided 45. We uncovered an elegy for a country gutted by wars, race riots, assassinations and generation gaps wider than the Grand Canyon. We disappeared into an amazing maze of pop-culture allusions. The line “Eight miles high and falling fast” referenced “Eight Miles High,” the Byrds’ helter-skelter rocker. “Helter Skelter” was the Beatles’ heavy-metal hymn that Charles Manson mutated into a murderous mission. The “generation lost in space” lost themselves in moon landings and the sci-fi TV show “Lost in Space.”

Gregg and I created a spacey fantasy around the couplet “While Lenin read a book on Marx/A quartet practiced in the park.” We replaced Vladimir and Karl, founding fathers of the Soviet Union, America’s greatest enemy, with John Lennon and Groucho Marx, radical quipsters who appeared on talk shows and in bedroom photographs. We had absolutely no idea that these revolutionary pundits would share a 1995 stamp issued by Abkhazia, a Russian republic.

We cast the Beatles in two roles: the park-practicing quartet and the marching-band sergeants who refuse to yield the football field after the fallout shelter falls. After all, we figured, didn’t the Fab Four masquerade as Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band? And doesn’t their namesake album cover’s choir of cut-out celebrities include Karl Marx?

Songs make us dance, romance, and retreat into a trance. “American Pie” made me a character in my own East End musical. I felt the narrator’s sock-hop jealousy while watching my eighth-grade crush dance with another guy to the Moments’ “Love on a Two-Way Street.” The bored Bonackers with whom I drank Boone’s Farm Strawberry Hill Wine in a pickup by a Wainscott beach reminded me of McLean’s “good ol’ boys” toasting their imminent deaths with whiskey and rye by a dry levee. I linked the levee to private jetties littering the sand like concrete buoys, eroding dunes they were designed to guard.

“American Pie” crowned a year of momentous firsts: first football heroics; first sexual experience; first betrayal. McLean’s hopeful rhythms consoled me after my father sold our Wainscott home without consulting my mom, who at the time was housesitting for my dad’s brother in California. In August 1972 we returned for good to our New Rochelle house, where we never lived as a whole family.

Buddy Holly inspired McLean to play music for a living, to make people “happy for a while.” McLean inspired me to write about music for a living. I mention “American Pie” before I ask musicians for the first song they couldn’t forget, the one that rearranged their vital organs. I channel the challenges of deconstructing “American Pie” before they deconstruct their own challenges: rewarding mentors; protecting protégés; hitting brick walls after breaking through.

I interviewed Mr. “American Pie” himself in 1984, two weeks after starting at the paper that employed me for 25 years. McLean spoke from his home near the Hudson River, nearly four miles from the birthplace of “American Pie.” I spoke from my mom’s home in New Rochelle, a special place for a special event.

McLean was equally engaging and elusive. Holly’s death devastated him because he considered the musician an unsung master and his “secret” agent/angel of good vibes. “As far as I was concerned,” he said, “I was the only person in the world who understood him, who dug him.” Remembering that piercing pain freed him to write a fable/parable about apocalyptic times in “the world known as America,” a national loss of innocence triggered by the day the music died. The overwhelming popularity of “American Pie” overwhelmed him; he learned the hard way that unfamiliar success is much harder to handle than familiar failure.

McLean declined to identify “American Pie” characters and meanings, sticking to a longtime script. All his songs, he insisted, were mostly “flashes of light, pure strokes of brilliance from somewhere, usually not from me.” He laughed when I told him about substituting Groucho and John for Karl and Vladimir. “Hmm, not bad,” he said. “I’ll give you an A for effort.”

McLean and I reunited for a 1999 story on Martin Guitar’s limited-edition, signature “American Pie” model, inlaid with seven of the song’s mythic names. He praised a beloved, long-lost Martin D-28 as “the rocket ship” that zoomed him to “some good places,” enabling him to buy the New Rochelle house his mother lost after his father died. Royalties from hit tunes — “American Pie,” “Vincent,” “Castles in the Air” — allowed him to afford rare Martins and a totem pole for his kids, a stand-in for a New Rochelle totem pole that was my childhood attraction, too.

“American Pie” looped through my system as I wrote “The Kingdom of the Kid,” a 2013 memoir about the South Fork in the late ’60s to early ’70s, the last gasp for a middle-class paradise. McLean’s bizarre bedfellows — the Bible and the Book of Love; the Rolling Stones and the Holy Ghost — encouraged me to pair baseball hall of famer Carl Yastrzemski and literary hall of famer Truman Capote, my chalk-and-cheese heroes. I opened the last chapter in Wainscott Cemetery, searching for my writing guru’s grave, as a tribute to McLean’s final verse, where the narrator searches for solace in the dead record store where the music thrived.

I don’t know why I left out my “American Pie” pilgrimage. Maybe it was because I lost track of my fellow pilgrim for 43 years. I finally met Gregg de Waal again in his East Hampton Star obituary, published in 2015, the year McLean’s “American Pie” manuscript was auctioned for $1.2 million. I was happy to know that Gregg loved fishing and dogs. He certainly looked happy in the obit photo, hugging his pup, his lighthouse eyes glowing.

Gregg and I shared a mystical moment during a 2016 reunion for the East Hampton High School Class of ’76, which I attended as a special guest of the East Hampton Middle School Class of ’72. We reunited at a table of photos of deceased graduates. I was staring at Gregg’s 17-year-old self when the DJ played — no lie — “American Pie.” In a flash we were teenage bronckin’ bucks, kicking off our shoes and blues in life’s rodeo.

Geoff Gehman is a former resident of Wainscott, a journalist and the author of the memoir “The Kingdom of the Kid: Growing Up in the Long-Lost Hamptons” (SUNY Press). He lives in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Email geoffgehman@verizon.net.