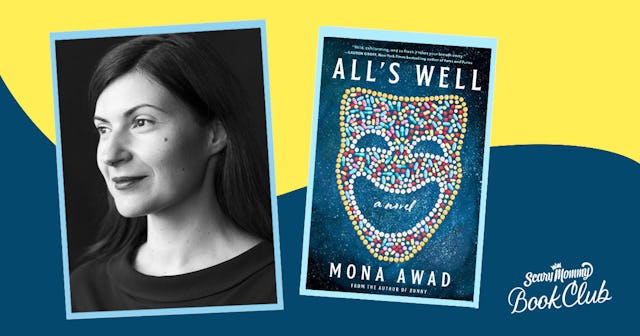

'All's Well' Author Mona Awad Talks Shakespeare, Horror, and Women's Pain

Mona Awad wants to make you laugh, cry, and think about women’s experiences with pain in her new book All’s Well

When Mona Awad was struggling with chronic pain, she noticed something when sitting in doctor’s offices and physical therapy waiting rooms: she was surrounded by women in pain, and those women were being dismissed by medical professionals and treated as invisible by everyone else.

Now, in her third novel, she’s had the chance to explore women’s pain in depth. In All’s Well, we meet a woman named Miranda—whose entire life was altered when she fell off of a stage and suffered chronic hip and back issues that have left her in constant agony. It ended her marriage, it ended her promising acting career, and now it’s threatening to even take away what she has left: a job as a theater professor at a small college who’s in charge of each spring’s Shakespeare play. But when a strange encounter with three magical men leaves her healed, she has the opportunity to see what the world is like when she’s healthy.

All’s Well feels like journey—and then it feels more like a trip—as we follow Miranda down the dark path of getting exactly what she wishes for. It also accomplishes the almost impossible balancing act of being a comedy and a tragedy at the same time, and one in which all we can hope for is a happy ending.

We sat down with Awad to talk all about the book, from her earliest experiences with Shakespeare to all of the novel’s nerdy hidden Easter Eggs, as well as chatting about her next project and some of her favorite recent reads.

First of all, we just want to say how much we enjoyed All’s Well.

That really means a lot to me, because it felt like a risk.

Why did it feel like a risk to you?

There were a few things. One was Shakespeare, which was very intimidating. And working not just with one play, but with two plays: a comedy and a tragedy.

I really wanted this director who is in great pain, Miranda, to want desperately to stage this comedy where all ends well—that’s the dream life that she has for herself—but then she has to live this tragedy that she doesn’t want off stage. I was thinking about how to strike a balance between those two energies: the energy of comedy and the energy of tragedy.

What’s your relationship to Shakespeare and how did you prepare to write the book?

I remember being 15 years old and having to do a monologue of of Macbeth, his famous soliloquy: Is this the dagger, which I see before me? And I remember my mother made me a tinfoil dagger and I held it up in front of the class and I was so excited. It was so dark and really appealed to my Gothic teenage soul. Then in my 20s I got kind of shy, even though I was really interested in theater.

I returned to it in my thirties when I was grappling with chronic pain and taking a Shakespeare class. I was looking for escape and the players gave that to me. I could just find myself in these narratives. They were so exciting, and they had these incredible reversals of fortune in them—that’s the thing about All’s Well That Ends Well that excited me so much. The heroine starts out powerless and then gains agency and fulfills her heart’s desire. I’m really interested in stories that use magic to explore the truth of the human heart and Shakespeare does that beautifully.

How did you come to find that play and why did you want to put a spotlight on it?

One: the heroine is very strange. She’s very polarizing. She’s supposed to be a hero that we root for, but she does things that are very disturbing. She’s lusting after this man who doesn’t want her and she turns the whole world of the play upside down just to get him.

Then there’s something else about the play that I find really fascinating: She’s a trickster when it starts. She’s so open with the audience, she shares her desire. She shares her sorrow. We feel completely bound up in it and super empathetic towards her, this poor powerless orphan, alone in this world and loving this man who doesn’t want her. Then she recedes to do her magic and we lose that connection to her. Shakespeare is counting on us to have made enough of a connection in that opening scene to be on board. She challenges us with her deeds, which are morally ambiguous. So I really wanted to explore that I wanted to explore that kind of mysterious heroine, who we know, but we don’t know.

You said that you struggled with chronic pain—and the book is really an exploration of women’s pain. Can you tell us a little bit about that?

The subject of women’s pain was very interesting to me because it’s something that I was exploring in my own life. And it was awful to go through this period of years. And I didn’t know that it would ever have an endpoint at the time. So many doctors just didn’t take me very seriously. I’d had a surgery, it was not successful. And so there was only so much they could do, but I would go to them and I would feel very dismissed. I felt very lost and and very powerless. And there were a lot of women that I met just in the course of recovery, waiting in the waiting room at physical therapy appointments who were grappling in the same way.

We were all in this limbo together. I thought, how interesting, because from the outside, you can’t see that we’re dealing with this awful debilitating pain that is impacting every aspect of our lives. You can’t see it, but we’re living it. I wanted to explore that: the interior reality of somebody who is grappling with pain that people can’t see, and by virtue of not being able to see it and by virtue of the fact that she’s a woman, diminish and deny it so that she’s left very isolated and desperate. And then where does that desperation lead her?

One of the most shocking moments of the book is when Miranda gives her pain to other people and she immediately starts to dismiss it. Like other people dismissed her own pain.

Yeah. It’s something that this dismissal of other people’s pain and how quick we are to do it. There is something extremely lonely about being in pain. There’s something about it that we just can’t communicate. It transcends language—you come up against the limits of other people’s empathy, but also just other people’s ability. Our ability to conceive of somebody else’s lived experience can only understand so much. So: what if I literalize the transfer of pain so that somebody could actually experience what this character is going through? And what are the ethics of that?

You describe pain so vividly in the first 100 pages, and by the time the pain goes away, the audience is relieved of that pain. We want her to keep being pain free. But also as soon as you’re pain-free, you forget what it feels like.

I’ll never forget this, this terrible cold I had—I remember this one because of how violently it came and how it overtook me for awhile. And I remember when my fever finally broke—I think I used the description in the book: it felt like this warring had suddenly just gotten turned off and all was quiet and peaceful again. I knew that I was better. And the next day I was already starting to forget that desperate state. I think it might’ve been Susan Sontag who said that illness and health are two different countries. And when you’re in one, you can never remember the other.

The ending of the book is very intense. Are we supposed to understand what happens?

One of the things that I love about Shakespeare, and the reason why we keep revisiting the plays, is because they’re so open they allow us to put together the pieces. I really wanted to offer that opportunity to the reader. I didn’t want to close things up too tightly, especially because there is the onstage narrative of All’s Well That Ends Well, then there’s also the offstage narrative, and both kind of reach a climax at the same time in that final sequence. It’s good for it to be mysterious because All’s Well That Ends Well is mysterious. It’s a very strange ending. It’s very disturbing, it’s unsettling. It’s happy, but you’re like, Hmm, really? I don’t know about that.

I was surprised after reading the book that it’s not marketed as a horror book.

Do I think it’s a horror novel? Yeah, I do. I think that it is destabilizing in the way that horror is destabilizing. And it’s going for a visceral reaction, which is one of the reasons I love horror. It’s so immersive and it does things to the reader against the reader’s will, makes the reader have reactions that the reader isn’t really in control of—that are physical, like fright.

And you could argue that Macbeth is a horrific play.

You had to consider people’s level of knowledge about Shakespeare when you wrote the book. Are there Easter Eggs in the book that we might not notice? How did you approach the challenge of writing for someone who might’ve only read Romeo and Juliet in high school and only kind of know what Macbeth is about from watching Jeopardy?

I think it was very important to me to have some Easter eggs in there. So the character is named Miranda after Miranda in The Tempest—that’s a bit of a nod to her role in the book. Theater is a world of illusion, and she is in the midst of an illusion of sorts that she is creating.

Then there are some masculine descriptions of the witches in Macbeth, and I really wanted to draw that out and play with the 2017 Me Too movement, which is when I was writing the book initially, and all of these men were coming out and saying that it was a witch hunt against them. I really wanted to play with that posturing of men trying to escape accountability by using that metaphor, so I made three male witches who were very, very scary to me.

Then there’s the Scottish bartender who is also in my mind doubling as the Porter. He has a tattoo of one of the Porter’s most famous lines down his arm. So anybody who knows Macbeth and knows the Porter will probably catch onto that.

But it was extremely important to me that anybody with just a passing knowledge of Macbeth and no knowledgeable of All’s Well That Ends Well could understand the book.

I think once I understood what it was at the core of each play—because they’re kind of connected—it was very simple. They’re both about people who have a hidden desire that in order to realize it have to make a transgression. Helen’s transgression goes down the road of comedy. Macbeth’s transgression goes down the road tragedy and evil deeds. But it starts out with the same thing: a hidden desire that you don’t have the power to fulfill.

What are you working on right now?

I’m working on a novel I’m almost finished. And it’s the third book in what I see as a series. It’s sort of a trilogy: Bunny All’s Well, and this book. This one is about a woman who gets sucked into a very sinister beauty cult, and there are red jellyfish and it is very scary. I’m enjoying that, but also creeped out by it. And it’s a fairy tale, too.

What are you loving right now that you’ve read recently, and what are your recommendations for our audience?

The first novel that I want to recommend is Come Closer by Sara Gran. And it came out almost 20 years ago. But it is about a young woman who is possessed by a demon. And when the book starts she may already be possessed. It’s fantastic. It’s very short, very, very elegantly written, very powerful. The voice is so immersive. It casts a spell and it’s really terrifying. I highly recommend it because there’s nothing that I’ve read like it.”

I’m also really looking forward to Stephen Graham Jones’ new one, My Heart is a Chainsaw. Very excited about that. And finally, one of my favorite for short story writers, Brian Evanson, just had a book come out this August called The Glassy, Burning Floor of Hell. So that was wonderful. Every time there’s a new Brian Evanson collection, I get super excited because the stories are so weird and creepy, and they always surprise me.

Join the Scary Mommy Book Club Community

It’s like a real-life book club, except we’re all snarky and very few of us are wearing pants. Find out what this month’s book is, get great novel recommendations, and a lot of laughs.