Near Darke

By Hank Nuwer

A quest for easy money brought two outlaws to Darke County on Sept. 4, 1923.

The big news of the day, discussed by old men playing dominoes in county cafes, was that new Italian Prime Minister wanted Italy out of the League of Nations, mad at the League censuring him over his invasion of islands belonging to Greece.

The hoodlums chose the quiet lunch hour to make an estimated $6,300 cash withdrawal from the Farmer’s National Bank. Their loot also contained additional bank notes previously signed by bank president Conrad Kipp.

The two parked their car, leaving the motor running (although you just never know when a potential car thief is near looking for a joy ride).

They removed a satchel from the trunk and sashayed through the front door. The two men in black wore disguises. One had pasted on a Groucho Marx moustache and the other a grey wig. Both had painted faces to thwart witness recognition.

They trained revolvers on cashier Joseph (Joe) Menke, and tellers Robert Kolt and Vernie Townsend. Then they included bank patron Jack Boyer who had selected a bad day to make a transaction.

“Hands up!”

This was a stickup.

The robbers ordered the employees to shovel loot through the teller windows.

After they stuffed the satchel with greenbacks, they departed growling threats of what would happen to Menke if he sounded the alarm.

He buzzed anyway.

The county sheriff and two deputies formed a posse of three. They took pursuit with their car’s red gumball machine flashing.

Witnesses said the bad guys went thataway, taking Broadway to Main street, racing eastward toward the Requarth pike in a high-powered, 8-cylinder Cadillac they previously had swiped from a Columbus taxi driver.

Driver Clarence Oyler had been roughed up, robbed of $32, and tossed on the ground as his taxi sped away.

A mile from the Farmer’s bank, the two robbers pulled over a spooked Chic Wright in his green Buick touring car. They waved their revolvers, took Wright’s car keys, and ditched the Caddie.

The two doubled back west and entered the paved Greenville-Piqua pike. Greenville authorities alerted authorities clear to Dayton, and someone reported a green car racing through Covington like a Buick outta hell.

For the time being, it looked like the pair had pulled off a perfect heist.

Then, in time, authorities made arrests. They charged a Springfield car salesman named Charles Floody after Joe Menke fingered him as one of the disguised men who robbed him.

Turns out Menke was wrong, fooled by the robbers’ makeup disguise. Floody was selling either an auto or an automatic pistol in Springfield at the time of the robbery.

He sued for a hundred grand in damages but a local judge denied the suit. It helped that local newspapers found evidence that while Floody wasn’t a bank robber, his reputation wasn’t exactly as pristine as a devotional speaker’s.

Three more arrests of what a Greenville paper called “shady characters” ensued. These charges also were abandoned as the main prosecutor found no incriminating evidence.

An additional three arrests of more males and a 25-year-old married woman dressed in all-black named Jean Foley then quickly followed.

By now you’d need a scorecard to keep up with the arrested and then freed suspects zipping in and out of local jails.

Nonetheless, two key arrests occurred based on a solid tip given by Jean Foley, the married girlfriend of one of two suspects.

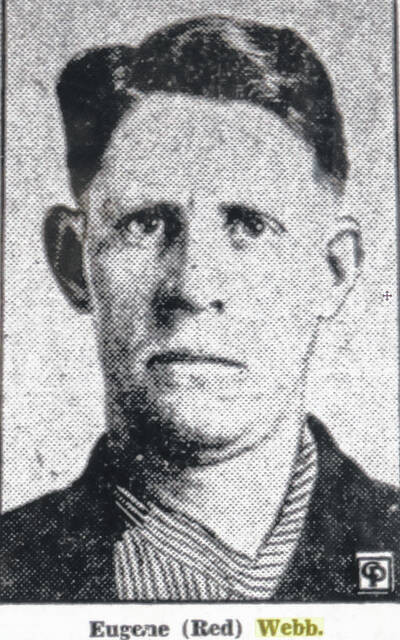

Police located boyfriend Eugene (Red) Webb as he enjoyed a drive in his freshly purchased $1,465 cream-colored Moon, ironically nicknamed “the honest car” by its independent manufacturer. Webb had a minor wound in his hip caused by a bullet, but he refused to say how he suffered it.

Police also arrested stout ex-con Burton Carter, 40, of Springfield, whom Foley called Red Webb’s accomplice.

A search of Webb’s home at 127 Mulberry street in Dayton turned up a revolver, rubber gloves, burglary tools, fuses and dynamite. Plus, police found the satchel with a stack of stolen bills and additional moneys Webb claimed to have “earned” by bootlegging.

Then, a farmer’s wife named Mrs. Milton Foulk of rural Springfield uncovered some of the missing loot buried on her property. She turned it over to authorities.

The reporter noted that Carter upon arrest wore a too-tight black sweater and a small black slouch hat atop his moon-shaped head.

Foley soon became a reluctant celebrity in Darke County as her case went to court.

Foley was “rather comely in appearance” noted a Greenville reporter. She sported a fashionable Roaring Twenties’ bobbed hair style as she appeared before Judge Teegarden while her indictment was read. “I don’t know what it all means,” Mrs. Foley told the judge while mysteriously smiling at Sheriff Browne, noted the same reporter.

“It means that you are charged with the robbery of Joseph Menke,” his honor retorted, slapping her in jail until cuckolded husband Joseph Foley could find a bondsman.

In a stunning subsequent teary-eyed confession, Mrs. Foley fingered Webb of Springfield as the brains behind the robbery.

She swore that this is what he admitted to her during their dalliances—including a love tryst to Chicago so Webb could put in his money in several banks (presumably more bandit-proof than the bank in Greenville).

She added that Webb — a World War One veteran and once a Springfield police officer drummed out in 1922 for conduct unbecoming — had promised to take her to a Lexington, Ky. horse track to dump the bank notes. That trip never occurred, however.

In a private interview with police on Oct. 1, 1923, and then in repeat performance Oct. 3 with police and the alleged robbers in attendance, Foley swore she had taken no part in the actual bank job. She blurted that her dear old mother had urged her to spill all and not take the rap for “dirty thieves.”

In a passionate outburst, Foley gave Webb a piece of her mind.

“I don’t see why God don’t strike you dead,” she told her now former lover. “I never was in trouble in my life before I met you.”

A shaken Webb broke down and cried as she lambasted him.

Police asked him what he had to say, and he clammed up.

She dropped a small bombshell when she accused Webb and Carter of pulling another job, a safecracking of a post office in St. Paris, Ohio, on Aug. 24 that netted $400 in stamps.

The ex-con Carter was calm and cool, denying any part in the holdup. He told the investigators that “they might as well write `finis’ to their little book.”

Foley went on to say that she learned later how her boyfriend and his crony had come to Greenville on Labor Day and scoped out the bank, a getaway route, and a list of places to hide their loot.

After dumping the stolen Buick and covering it with leaves and tree branches, Webb and Carter made their getaway by motorcycle, Foley said.

Foley finished her accusations by revealing where some of the loot was hidden.

Armed with her directions, Darke County law enforcement and members of the Ohio Banker’s Association combed a 35-acre woods with shovels and pitchforks.

They discovered a buried, handmade tin ash can containing four Colt revolvers, along with ammunition belts, more boxes of ammo and three Savage rifles. They also found the face paint, moustache and wigs worn during the Greenville bank robbery.

With evidence and Mrs. Foley’s accusations in hand, Webb and Carter soon were convicted and sentenced each to 25 years in the Ohio penitentiary.

Jean Foley could have gone to prison as an accessory. Instead, her mother’s urgings to come clean saved her a stint in prison.

The state dropped all charges.

That’s when the story gets interesting.

In October 1923, a Mr. Elchorn approached Greenville authorities and charged that Webb and Carter were the two men who strong-armed him near Hamilton, Ohio, and stole his Nash later used during the ambush of an Indiana sheriff prior to the Farmer’s National robbery.

On Aug. 23, 1923, Sheriff William Van Camp of Brookville, Ind., approached Elchorn’s vehicle on a tip from a local farmer, thinking he might be confronting two rum runners.

Instead, the two men were Webb and Carter. They were casing a local bank for a planned heist.

Van Camp fired twice at an occupant or occupants of the Nash but missed.

Carter shot back and Van Camp slumped to the earth, dead where he fell.

Mrs. Van Camp assumed her husband’s duties as acting sheriff, vowing to bring his killers to justice.

Evidence uncovered in the Greenville holdup was again examined. Investigators claimed that the cache of seized ammo included 100 bullets marked with a scratched cross on each.

Mrs. Van Camp maintained the bullets matched the fatal, expanding dumdum bullet removed from her husband’s corpse.

Webb, by February 1924, was interviewed by a private investigator at the state prison and supposedly fingered Carter as the sole killer. He said he ran back to the Nash from nearby woods after hearing shots.

You can believe Webb or not. He either saw Van Camp’s death or he didn’t.

“Hurry, let’s get out of here,” Carter snapped, according to what Webb allegedly told the private investigator.

The two desperadoes abandoned the Nash and stopped another driver to snatch his car for an escape to the Dayton area, claimed the investigator. From there, with the sheriff’s blood allegedly on their hands, they made final plans for the Greenville bank robbery.

Webb soon recanted while in the penitentiary, saying he never confessed and never had accused his old partner in crime of murder.

Mrs. Van Camp petitioned to have Webb and Carter extradited to Indiana, but Ohio Gov. Alvin Victor Donahey blocked the request. Stubbornly, he said that it was punishment enough for the convicts to serve out their sentence in the Ohio penitentiary.

The years passed. Webb served his time without trouble.

However, Carter was pure trouble, involved in numerous breakout attempts.

Once, he stole a vehicle behind prison walls, crashed a prison gate, but was tackled and subdued by an unarmed citizen.

Then in 1939, Ohio newspapers again focused on Webb and Carter. Penitentiary officials set them free in spite of the indictment for murder in Ohio and a federal charge in the post office burglary. Warden Frank D. Henderson said he had received no paperwork to keep them in their cells.

Then, extradition papers were finally filed in Indiana, and separate manhunts began.

Red Webb, now 41, was arrested without incident in Springfield by a former cop who once had served with him.

Burton Carter, 53, made it across state lines to West Virginia. There, a Wheeling arresting officer named Clarence Custer shot him several times front and back. Custer said Carter had resisted arrest.

Law enforcement brought him back in an ambulance for a murder trial in Brookfield he now never would face. Carter died in agony, his spine shattered.

The dying man refused to make a deathbed confession requested by Indiana authorities.

In Springfield, Webb refused to accept extradition.

Harry Miller, executive secretary to the then-Ohio governor, ordered a hearing attended by Indiana officials, supporters of Webb, and the widow of Sheriff Van Camp.

“The people of Springfield are greatly interested in giving this man a chance,” argued Horace J. Keifer, Webb’s attorney.

Sheriff Van Camp’s widow had remarried. Bertha Baker expressed outrage over Keifer’s statement.

“What if your wife had been killed 16 years ago?” Baker snapped. “Don’t think because he sits there suave and well-dressed that he isn’t a killer at heart.”

Nonetheless, Baker expressed sympathy for Webb’s mother after the hearing ended. The two mothers clutched hands. “I feel so sorry for you,” the sheriff’s widow told Mrs. William Harber.

Ohio Gov. John W. Bricker refused to grant Indiana the authority to seize Webb. Newspapers speculated that Bricker considered the former policeman “reformed.”

Eugene Francis (Red) Webb lived a quiet life in Springfield as a stenographer and bookkeeper, using skills he had mastered while incarcerated.

Before his death on August 5, 1962, he requested a military headstone in view of his service to his country from 1916 to 1919.

The request was granted. He was buried with military honors in Springfield’s Ferncliff Cemetery.

Ironically, his former lover Jean Foley whose testimony put him away, died in 1946, and was buried in the same cemetery.

In spite of the circumstantial evidence of the dum-dums linked to both the Greenville bank robbery and Van Camp’s death, the case today is as cold as an Indiana winter.

“Webb better not set foot in Indiana,” snapped Indiana prosecutor Orville A. Young after Webb’s extradition was denied.

Chances are, Webb never did.

Hank Nuwer is an author, columnist and playwright. He and wife Gosia live on the Indiana side of the Union City state line.

Viewpoints expressed in the article are the work of the author. The Daily Advocate does not endorse these viewpoints or the independent activities of the author.