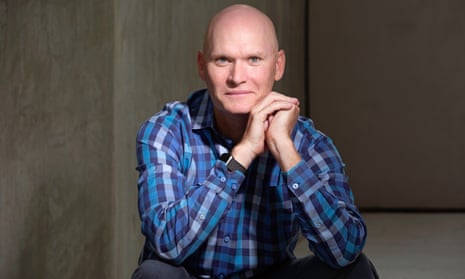

Anthony Doerr, 47, is the author of six books, including All the Light We Cannot See, which won the Pulitzer prize for fiction in 2015. The story of a blind French girl and an orphaned German boy during the second world war, it is the biggest selling title in the history of its UK publisher, Fourth Estate, home to Jonathan Franzen and Hilary Mantel. His new novel, Cloud Cuckoo Land, spans medieval Constantinople, a 22nd-century spaceship and a public library held under armed siege by a teenage environmentalist in modern-day America. Doerr, who grew up in Cleveland, Ohio, spoke to me from his home in Boise, Idaho.

You’ve described Cloud Cuckoo Land as a “literary-sci-fi-mystery-young-adult-historical-morality novel”. Where did it start?

When I had a fellowship at the American Academy in Rome [in 2004], it was the first time I’d been around classical scholars, who taught me how few ancient texts actually survive. I guess I’ve always had a terror of erasure, going back to when I was 12 or 13 watching Alzheimer’s devour my grandma’s sense of self, and I found myself wanting to tell a story about the beauty of how culture endures. I’d been researching the history of defensive walls to write All the Light We Cannot See, particularly Hitler’s Trump-like dream of a wall from Sweden to Portugal, and everything I read would mention Constantinople, whose walls withstood 23 sieges over 1,100 years. I was like, Constantinople? We didn’t learn about it at school for one second. But rather than write what I know, I write what I want to know, which was how those walls protected Byzantine book culture.

The novel is partly set on 20 February 2020. Did the pandemic end up on your mind too?

For sure. I sent my editor the book on 31 March last year but I’d been trying to imagine what kind of future I could present to the reader and I knew pandemics could be part of it. In 2016 I had read David Quammen’s book Spillover, which talked about how the more we encroach on natural habitats, the more likely it is that animal viruses enter the human population. I’d also been reading about how, in 1453, so many people inside the walls of Constantinople really believed it was the end of the world, which is an idea I’ve always been interested in. The whole seven years I was writing this book, American culture was feeding these dystopic narratives to my twin sons, from age 10 to age 17; every time I went downstairs, there was an Earth blowing up on television or a city disintegrating while Iron Man does laps around it. I thought, what is that doing to us? Why are we so obsessed with the end of things? And can I counter that, even as I play with it?

A key thread involves an elderly war veteran trying to protect children from Seymour, a young backpack bomber radicalised by climate change…

Environmentalists ask, what kind of ancestor am I being? My wife’s father, for example, is in every definition an incredibly good person. I don’t think he’s told a lie in his entire life. He’s so kind and so morally sound, and yet in business he flew on planes all the time. By what calculus will our great-grandchildren measure good behaviour? Maybe it’s just how many resources we’ve used. I’m still a meat eater. I’m trying to eat far, far less, but maybe that is the single thing that will judge me poorly – like, it doesn’t matter if you went to an Earth Day march, because when you drove there you drank from a plastic water bottle, you know? Seymour’s sensitivity makes him, I think, a new kind of hero, but I understand that his behaviour will turn a lot of readers off, because it’s violent.

Imaginative storytelling is sometimes portrayed as outmoded or even ethically suspect amid the rise of autofiction and concerns over cultural appropriation. Do you feel as if you’re defending its virtues?

I don’t live in New York City; I live in Idaho, where many of us are readers and really bright people but just aren’t in that literary zeitgeist and so don’t deal with those anxieties. I got into reading to leave my own life – not to escape my own being, but to multiply it by exploring other experiences. That doesn’t mean I don’t love a writer like Rachel Cusk, who is so exciting and so good with sentences and similes, but in my own work I’m drawn to experiences different from mine, and how I can do as much learning as possible about them.

How involved are you in the forthcoming Netflix adaptation of All the Light We Cannot See?

Steven Knight [of Peaky Blinders] is writing it; although I’ll happily read drafts, writing something I’ve already written doesn’t interest me. It’s fun to listen in, but it’s a reminder that, as prose writers, our materials are so democratic. Not once while writing All the Light did I think how much it costs to blow up a building; my budget was just the cost of a sandwich every day.