Stop by the Potbelly Sandwich Shop in downtown Rochester, and you'll be met with a locked door and a sign telling you the restaurant has closed.

Whether that closure is permanent or not, said co-owner Erin Nystrom, doesn't depend on the amount of business the store receives, but on the number of employees she can hire.

"It always has been a struggle to get good employees," Nystrom said. "We're down to 13 employees from 40 two months ago."

ALSO READ: ‘Rochester stands together’: Insider stories from 500 days that changed Rochester business

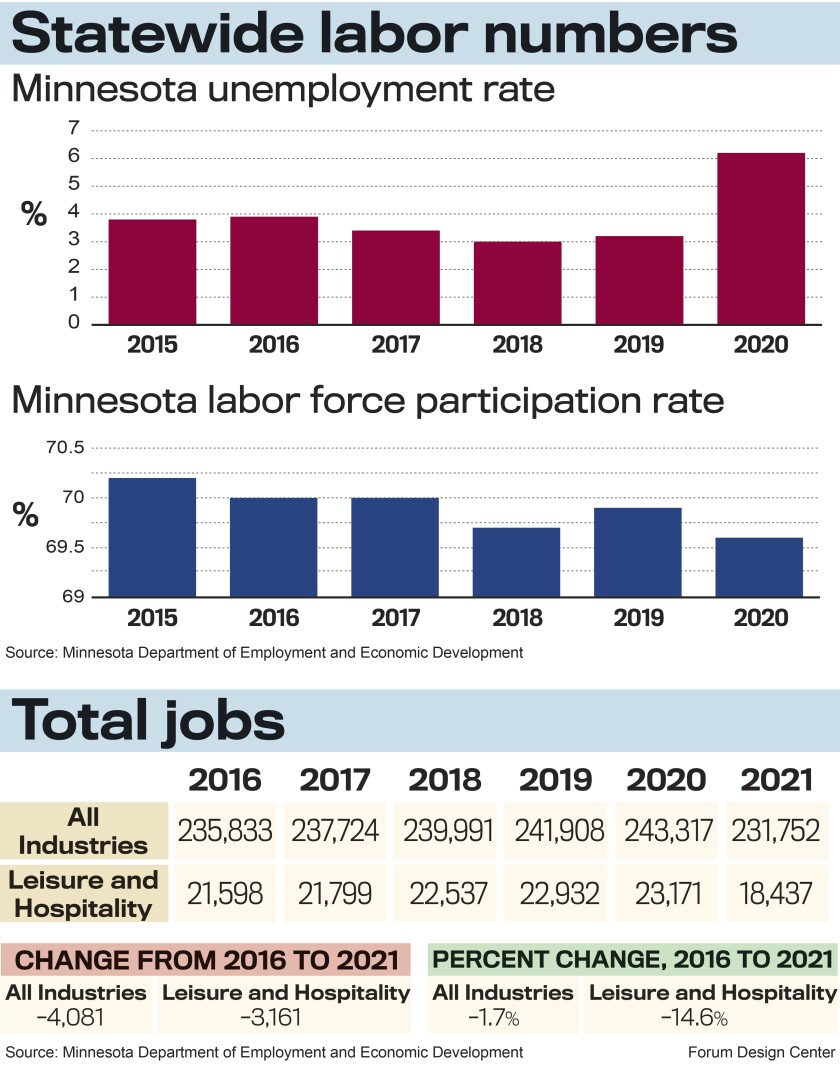

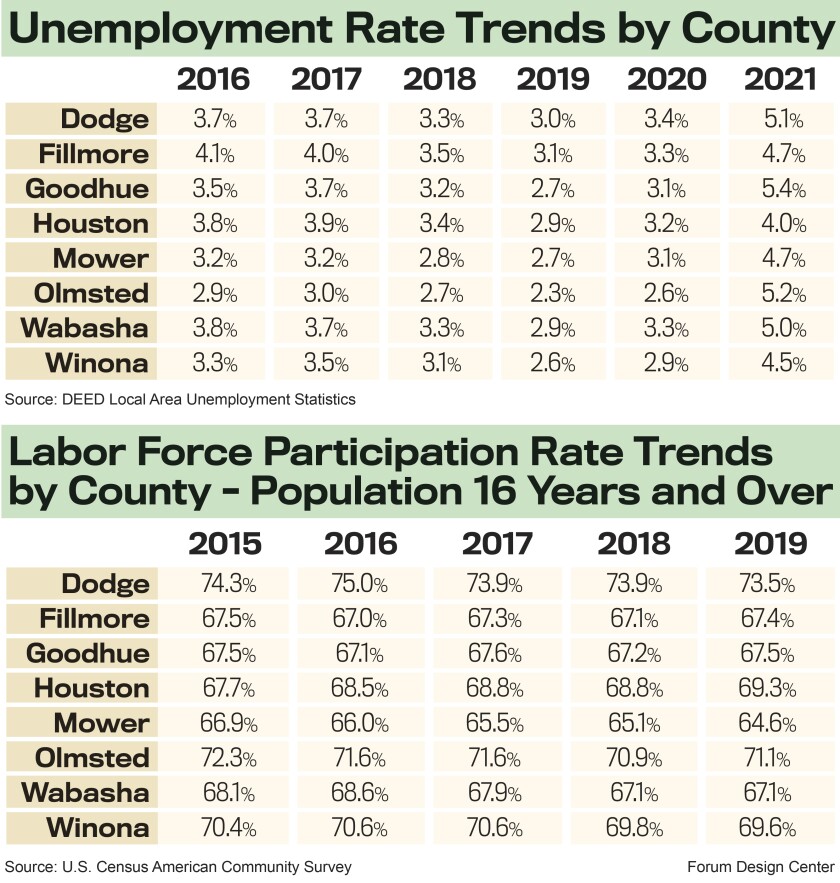

In Minnesota, the unemployment rate nearly doubled from 2019 to 2020, and the labor participation rate has shrunk a full point in five years. To top that off, the hospitality industry has seen the biggest drop in jobs, and the shortage of labor has come from many places.

ADVERTISEMENT

For Nystrom, she's seen employees going back to school, people who have left during the restaurant shutdowns caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, and some hard-working employees have called it quits because customers expect the same level of service today that they received pre-COVID, even though there are fewer people serving them.

Angry customers vs. good job

Nystrom's second location, on Marketplace Drive near Target on 41st Street Northwest, is still open, but Nystrom said it's hard to keep the restaurant going. Customers take out their frustrations on overworked staff, and people who don't like the store's mask requirement either simply leave or curse her employees.

"Employees leave because they are sick and tired of being treated this way," Nystrom said. "The stress is customer-driven. They're unhappy about the masking policy, and people write reviews on Facebook or Google. On the website."

Nystrom said she's simply trying to protect her employees, people who deal with dozens of customers a day, face-to-face in a public indoor setting during the delta-variant increase of cases both locally and nationally. One positive case among her employees would likely close her store for more than a week.

"As if working in a restaurant isn’t hard enough as it is," she said. "Masks are a basic safety mechanism against the delta variant. Why can't people give restaurants a little grace?"

It's not that Nystrom isn't paying good money for employees. A general manager for one of her restaurants makes more than a school teacher, she said. Shift leads start at $15 an hour. Despite competitive wages, the hiring process is difficult. Many people don't even show up for their scheduled interviews, and some new employees get trained and work a handful of shifts, then just quit.

ADVERTISEMENT

"The labor market is unreal," Nystrom said. "I don’t know where everybody is."

One problem, many reasons

Whether it's restaurants and bars or hotels, keeping hourly workers at this stage of the pandemic has been difficult for businesses in Rochester, said Holly Masek, executive director of the Rochester Downtown Alliance.

"I’ve heard many, many, many different reasons for it," Masek said. "The recovery is happening in a bumpier way than anyone imagined."

Masek said there was certainly a workforce shortage before the pandemic and its business shutdowns and mask mandates began in March 2020. That sent a lot of hardworking individuals home. And those people, especially hourly shift workers, began to re-evaluate their lives.

"When some of those people were furloughed, they moved on," Masek said. "For a while, it was scary to be in a customer-facing role."

Alaina Pappas-Mitchell, manager of Hubbell House in Mantorville, said one server who'd worked at the restaurant for 10 years took the opportunity of being laid off to start working toward becoming a paramedic and to join the Kasson Fire Department.

ADVERTISEMENT

"Servers, a lot are part-time to begin with or are seasonal," Pappas-Mitchell said. "When the shutdown ended, a lot of them did not come back."

Whether it was the server who wanted to become a paramedic or people who, after living without the income of a second job, decided they liked the extra time off, COVID-19 gave people time to think through some employment changes.

"You can’t be mad at those people for wanting to make a better life or do something different," Pappas-Mitchell said. "But we feel it here."

Masek pointed to other COVID-related impacts that led to lifestyle changes. For example, parents who spent time at home with younger children decided to stay home with their kids. Sometimes, it was the distance learning – and the uncertainty of even the just-started school year – that has kept some individuals from heading back to second-income jobs.

Back to normal yet?

That doesn't change the fact that through the spring and summer, as mask mandates were loosened and businesses welcomed customers back to in-person experiences, the expectation of the return to the pre-COVID world met the harsh reality of that bumpy recovery.

"I think it's extra hard on the morale of the employees that are there," Masek said. "People want to dine out and travel, but we'd ask them to try not to rush anyone because the whole country is short-staffed."

ADVERTISEMENT

On the door at Hubbell House is a sign asking customers to take their time, relax and have patience with the staff because, while the restaurant is open, things have changed.

Those changes, Pappas-Mitchell said, come in many forms. For example, while finding good servers is hard, it's even harder to find enough cooks in the kitchen. So, when a customer walks in – Hubbell House prefers to take reservations, but will seat walk-in customers – and sees plenty of open tables, it can be confusing as to why they aren't being seated, or are told their dinner might take a while.

"I try to be upfront with them," Pappas-Mitchell said, adding that communication can help. "But people don't see the back of the house. They'll see open tables. But if I seat four more tables, if I add another server, it would bury the back of the house. We’ve been in that situation a few times, and it’s not fun."

The restaurant, a landmark that has been open for 75 years in Mantorville, is doing other things differently. Pappas-Mitchell said they've changed the menu because some items take too much work for the smaller staff. They control seating at the bar more now than they used to do. And they've even changed hours – reducing lunch shifts to Fridays and weekends – to close earlier to save money.

As for the COVID impact, Pappas-Mitchell agrees with Nystrom that a positive case among employees could have a devastating effect.

"This is our new normal, and people need to understand that," she said. "It will get better, but until it does, we need our customers to be understanding with us. Just giving the cook or the server an extra thank you does so much. Those little words can mean a lot to someone."

The job market

Pappas-Mitchell said that when the initial restaurant and bar shutdown occurred, Hubbell House reduced staff to just managers, to handle takeout orders. But when the restaurants reopened last year, they could not hire back everyone who had been on staff.

"It was unknown how busy we would be, and we didn’t want them to not have hours," she said.

ADVERTISEMENT

This summer, the staff was fairly full, but that changed when school started and the teen and college-age staffers left. That, Pappas-Mitchell said, is a normal part of business.

A bigger problem, she said, is that working as a server is looked down upon as a career, and society as a whole needs to stop normalizing the Monday-Friday workweek. Even kids – teens and college students – don't want to work nights and weekends. That demographic had long been a staple of the hospitality industry's workforce.

Jinny Rietmann, executive director of Workforce Development in Rochester, said many of the factors that are plaguing the hospitality industry have impacted other workforce areas as well.

"Hospitality's been hit the hardest," Rietmann said. "That’s the industry that had the most layoffs, the industry with largest labor shortage."

Solutions, she said, include job training programs and career planning advice that Workforce Development offers, but, "at the end of the day, it’ll take all these efforts working together to turn this economy around."

Rietmann said the idea that people are not re-entering the workforce because of unemployment benefits that were increased during the bulk of the pandemic is not true, a statement Pappas-Mitchell and Nystrom agree with.

ADVERTISEMENT

"People out there want to work," Rietmann said, "but there's an opportunity mismatch. The people we’re seeing are facing a number of barriers to employment."

Those barriers include everything from lack of trade skills necessary for the building or manufacturing industries to those people skills needed to work in hospitality. And, she added, there's a huge number of people who took the time during COVID-19 to re-evaluate their lives.

"Your whole workforce might look different in a couple of years, but we keep expecting things to go back the way they were," she said.

She said that along with hospitality, the health care field is undergoing changes as people who worked on the front lines during the pandemic start looking for a new career. Some, she said, have decided that vocation of healing is no longer worth it.

Some people are simply retiring earlier. On the younger end of the workforce, teens and twentysomethings are delaying entry to the job market.

In some cases, it's because young people lack the guidance to find their niche in the workforce, said Julie Brock, executive director for Cradle 2 Career, a nonprofit that looks to eliminate educational and racial disparities on a communitywide basis for people looking for guidance. While the organization works from pre-kindergarten through high schoolers, helping with everything from school readiness standards to career advice, Block said one of its key programs is a mentorship program for teens.

"Kids don't know what's available to them after high school," she said. "There's a disconnect in high school about what's happening next. We want to know how many kids have a post-secondary plan. We work with kids to understand what their next step can be."

What is vital is finding those strengths a teen might have and helping them find a career path that capitalizes on them, whether it is math and science or the people skills necessary for health care or hospitality.

"Many of our kids really don't know what they're being prepared for," Block said. "They're given a track and told to get good grades."

She said we also need, as a society, to value those hospitality jobs that provide a cup of coffee mid-afternoon or a relaxing meal in the evening. Part of that is to create training programs that improve workers' skills in those areas so they can work their way up to better jobs within the industry.

For Nystrom, she'll keep posting help-wanted ads and hoping for the best. There has always been turnover at her restaurants – in the whole hospitality industry – but the pandemic and the slow, uneven recovery, have made things worse.

"Turnover is very high right now," she said. "The minority of folks we hire will stay. You wonder how any small business makes it anymore."