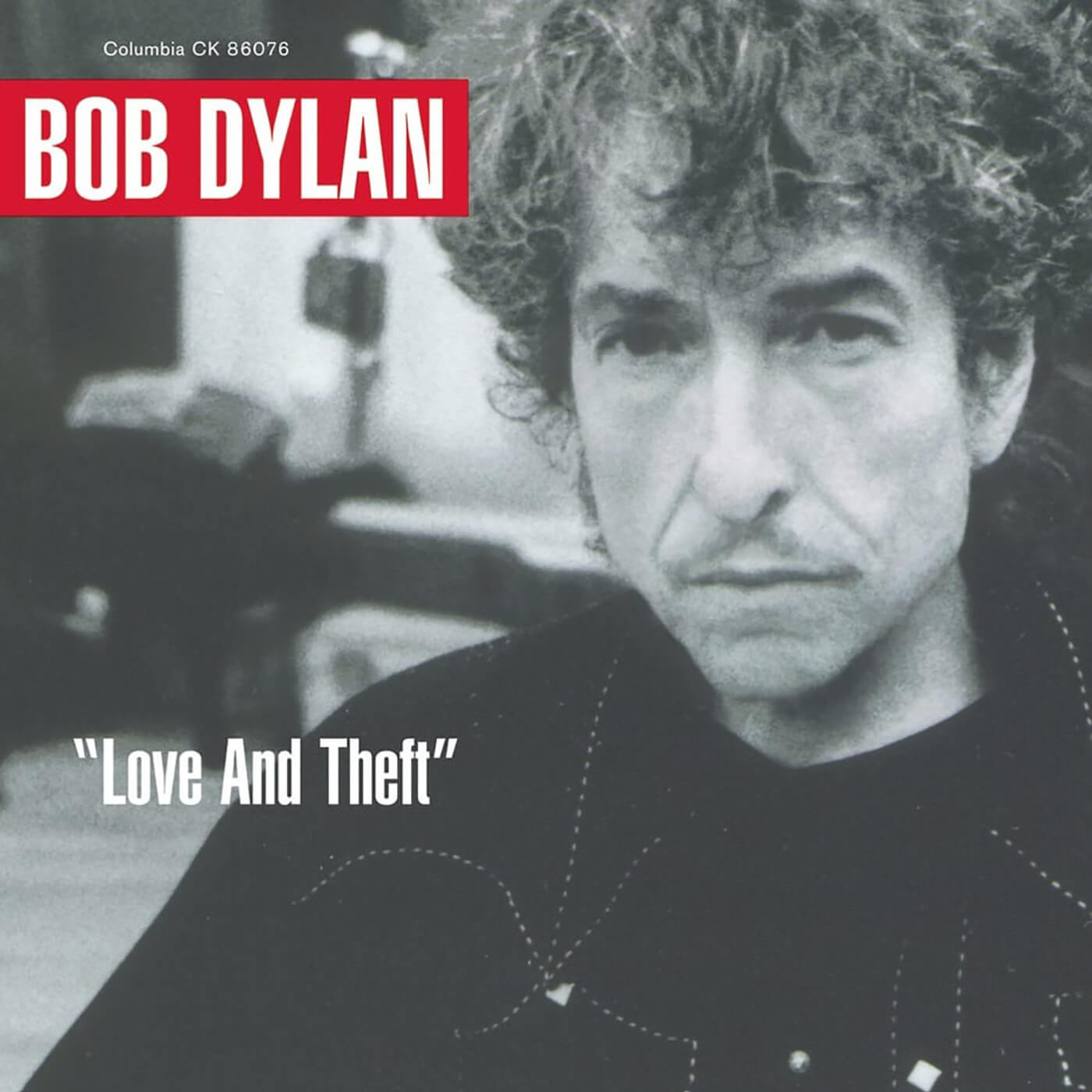

The Genius Of… Love And Theft by Bob Dylan

Released on a momentous, tragic day 20 years ago, Bob Dylan’s 31st album is an intricately layered tribute to the roots of American musical history.

Image: Harry Scott / Redferns

“The songs don’t have any genetic history,” Bob Dylan informed USA Today as he unveiled his 31st studio album on 11 September 2001. Yet Love And Theft is Dylan’s comprehensive love letter to pre-rock American music and his most emphatic salute to blues guitar since the untouchable mid-60s trio of Bringing It All Back Home, Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde.

The title, taken from Eric Lott’s Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy And The American Working Class, reads like a playful acknowledgement of Dylan’s admiration and appropriation of pre-war music. Throughout this densely woven tapestry, music’s most discerning magpie channels the sound of everyone from Robert Johnson to Hank Williams, the Carter Family, Muddy Waters, Frank Sinatra and Charley Patton, weaving together Appalachian folk, rockabilly, vaudeville, swinging country and all corners of the blues. It’s Dylan at his lovelorn, hilarious, enchanting and baffling best at the dawn of a new millennium.

In 2001, Dylan’s band, rated by Love And Theft engineer Chris Shaw as the best he’s ever played with, were in red-hot form, clocking up 106 dates as the Never Ending Tour powered through its 14th year and Dylan turned 60. With that momentum in his sails, Dylan took the band, including Texan guitarist Charlie Sexton and session veteran Larry Campbell into New York’s Clinton Studios.

Having ditched A-list producer Daniel Lanois, Dylan took care of business himself, under the pseudonym Jack Frost. Recording a song a day for 12 days, the atmosphere was loose with everything tracked live, Sexton and Campbell having learnt to find space for their riffs and solos between Dylan’s avalanches of words. Mr Frost, trying to summon the spirit of Robert Johnson, initially demanded his vocals be recorded in a corner of the room, facing a wall, but after two minutes was sat the piano as the band played around him. The sessions were, recalls Shaw, “a blast”.

Greatest hits without the hits

Dylan would turn up at the studio each day with piles of old records, ask the band to learn them, and then shift focus to his own songs. “I’ll take a song I know and simply start playing it in my head,” he explained of his writing process. “At a certain point, some of the words will change and I’ll start writing a song.” Drummer David Kemper told Uncut: “It was like, ‘Oh God, he’s been teaching us this music, these styles’. That’s why we could cut a song a day for 12 days.”

Yet the 12 songs on Love And Theft belong wholly to Dylan, who would command his band to switch tempo, key and feel at the drop of a hat, refusing to wear headphones as he recorded. With Dylan largely at the piano, Campbell played guitar, mandolin, pedal steel and bouzouki, while Sexton’s accomplished blues riffs are dispersed all over the album, twining around a catalogue of unconventional chord shapes. “There aren’t any of my songs Charlie doesn’t feel part of,” Dylan told the New York Times. “He’s very restrained in his playing but can be explosive when he wants to be. He inhabits a song rather than attacking it.”

The first signs that Dylan was germinating what he called “a greatest hits record… without the hits,” came when he played Campbell the comedic Po’ Boy, with its sparkling acoustic fingerpicking and David Kemper’s jazzy brush flourishes, and inspired by the 1920s country ballad Wanderin. The source that everything draws from, though, is the swampy Lonesome Day Blues, Dylan lifting the first line from Muddy Waters and setting his version in A flat. The scintillating lyrical performance from the two guitarists recalls Robbie Robertson lighting up Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat on Blonde On Blonde.

I’m drowning too

As ever with a Dylan album, there are infinite layers to unravel. Love And Theft features a dizzying roll call of voices, characters and impenetrable references – Romeo and Juliet, Othello, Desdemona, Charles Darwin, the Devil and God all make appearances in these complex folk tales.

The band are right in the pocket from the onset of Tweedle Dee & Tweedle Dum, a shuffling blues in B, based around Johnny & Jack’s 1961 song Uncle John’s Bongos. A devilish riff recurs, with Dylan’s vocal by now a weathered growl as he sings “They’re making a voyage to the sun/ His Master’s Voice is calling me,” one of several references to Elvis on the album.

Love and heartbreak are always near the surface, too. On the sweet country-flecked ballad Mississippi, an outtake from Time Out Of Mind also recorded by Sheryl Crow, Dylan tells his loved one ruefully, “Your days are numbered, so are mine” as the acoustic rhythm cycles gently between C/Csus4/F.

Summer Days has its roots in rockabilly, Campbell and Sexton sketching artfully over an irresistible 12-bar blues; there are vaudeville notes to Bye And Bye – a nod to Billie Holiday’s Having Myself A Time – and Floater, while the Delta blues in G tribute High Water (For Charley Patton) is exceptional. Rootsy acoustic chords tangle with Campbell’s frolicking banjo work as Dylan issues the fatalistic warning “Don’t reach out for me, Can’t you see I’m drowning too”.

Finally, we arrive at the majestic acoustic ballad Sugar Baby, the latest in a long line of stately Dylan album closers. The altered-tuning silvery acoustic strums in the right channel are met with subtle adornments in the left and the sprightly embrace of an accordion, as he appropriates the line “look up, look up, seek your maker/ ‘fore Gabriel blows his horn” from The Lonesome Road by Gene Austin and Nathaniel Shilkret.

Love on the side

While not embraced as immediately as Time Out Of Mind, not least because it was released on the day of the September 11 terror attacks – leading to some bizarre conspiracy theories from Dylanologists – Love And Theft has since been recognised as one of Dylan’s seminal albums. Reaching No.3 in the UK charts and No.5 in the US, it was his biggest chart success since 1979’s Slow Train Coming. It won Best Contemporary Folk Album at the 44th Grammy Awards, topping The Village Voice’s Pazz & Jop poll and Rolling Stone’s 2001 list. It’s regularly named in the top 10 Dylan records of all time, and Johnny Cash told the New York Times that it was his old friend’s best album.

Asked to explain Dylan’s enduring brilliance, U2 frontman Bono could only reply: “It’s like trying to talk about the pyramids. What do you do? You just stand back and gape.”

“We’re all just lucky that we live in this particular time when we get to have Bob’s great influence,” gushed Tom Petty, while Joni Mitchell contended: “No one has come close to being as good a writer as Dylan.” The critics agreed, Ian Penman writing in Uncut: “Dylan is our first rock star grown old, really grown old, and one happy to let it show.”

The Never Ending Tour rolled on beyond Love And Theft, Dylan returning to Newport Folk Festival in 2002, 39 years after his first appearance, although there were changes afoot in one of his greatest band line-ups, with Campbell departing in 2004. Two years later, Dylan released what he regarded as the second instalment in a trilogy begun by Love And Theft. Modern Times was a US No.1 that confirmed we were in yet another Bob Dylan golden period.

“I don’t feel like what I do qualifies to be called a career,” Dylan told Rolling Stone two months after releasing Love And Theft, one of his truly great, defiant, surprising statements in a career ludicrously rich with such moments. “It’s more of a calling.”

Infobox

Bob Dylan, Love And Theft (Columbia, 2001)

Credits

- Bob Dylan – vocals, guitar, piano, production

- Larry Campbell – guitar, banjo, mandolin, violin

- Charlie Sexton – guitar

- Augie Meyers – accordion, Hammond B3 organ, Vox organ

- Tony Garnier – bass

- David Kemper – drums

- Clay Meyers – bongos

- Chris Shaw – engineering

Standout guitar moment

Lonesome Day Blues

For more reviews, click here.