Michael Peckham, who has died aged 86, did much to advance the acceptance of evidence-based medicine. This approach – using well-controlled clinical trial data for improving the treatment of patients – has never received greater attention than now, during the Covid-19 pandemic.

In 1986 he moved from trailblazing clinical work as a professor at the Institute of Cancer Research and the Royal Marsden hospital, London, to become director of the British Postgraduate Medical Federation, then a loose association of seven institutes based in the capital. His restless mind envisaged an opportunity for much closer collaborative work between those high-level centres, aiming at advances that would otherwise have been impossible.

Five years later he was made the first NHS director of research and development, with a clear view of what was needed: “A prime objective is to base decision-making at all levels in the health service – clinical decisions, managerial decisions, and the formulation of health policy – on reliable information based on research.”

He supported “blue-sky thinking” so that the NHS could benefit from speculative ideas being tested in clinical trials. In 1992 he ensured funding for the Cochrane Centre “to facilitate the preparation of systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials of health care”.

It was named after Archie Cochrane, the initiator of the first systematic attempts at pulling together robust evidence from controlled trials for assessing clinical treatments, rather than depending on the traditional “but we’ve always done it this way” approach. Now as the international collaboration named simply Cochrane it has more than 50 review groups worldwide and 30,000 doctors, scientists and statisticians available as expert reviewers, providing authoritative assessment of much hyped new treatments.

In 1999 Peckham’s tenacity and vision led to the establishment of NICE, now the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, which has had a major impact on the way medical advances are applied today, and has been emulated elsewhere.

The close working partnership between NICE and the NHS-science-linked Biomedical Research Centres, also fostered by Peckham as NHS research director, has underpinned the UK’s remarkable success in helping to unlock the secrets of the pandemic and speedily introducing validated treatments.

Meanwhile, Peckham’s restlessness took him to University College London as founding director of the school of public policy (1996-2000). Just before his arrival the department had only three professional staff, but today has 50 members of staff including no fewer than 12 professors. He also chaired the Office of Science and Technology’s panel on the future of healthcare (1999-2000).

The zeal behind such research and policy initiatives came from Peckham’s two decades of working as an oncologist. He pioneered new treatments for cancers in young people and raised public awareness of a disease that was largely taboo when he started out, in the late 1960s. At the forefront of modern treatment for testicular cancer, Peckham achieved an international reputation for research into combination chemotherapy, resulting in spectacular successes even in patients with advanced and widespread disease.

Perhaps most notable was the jockey Bob Champion, discharged after his final gruelling treatment and within a few months scoring one of the most stupendous wins ever, in 1981’s Grand National, steering home the elderly Aldaniti. Unlikely indeed – only the ward sister had the chutzpah to place a decent-sized bet – at terrific odds. The rest of us watched from behind the sofa.

Peckham led the way in setting up international cross-disciplinary academic groups that continue to thrive today, including ESTRO, the European Society of Therapeutic Radiation and Oncology and the Federation of European Cancer Societies, now the European Cancer Organisation. His commitment to a pan-European ideal for research was reflected in his highly authoritative Oxford Textbook of Oncology, published in 1995, the year in which he was knighted. He was awarded honorary degrees from several British and mainland European universities.

Born in Panteg, Monmouthshire, Michael was the son of Gladys (nee Harris), a schoolteacher, and William Peckham, who worked on the railways. Michael attended Jones’ West Monmouth school (now West Monmouth school). At St Catharine’s College, Cambridge, he graduated in natural sciences (1956) and as a medical doctor (1959), going on to train in clinical medicine at UCL medical school.

After undertaking junior posts in London, he decided on a career in research and went to Paris, working at the Institut Gustave Roussy (1965-67) on the cell biology of lymphoma with the groundbreaking researcher Maurice Tubiana. During this fruitful period he acquired a lifelong love of France, and later played a significant role in drawing on the great tradition of French radiobiology that stretched back to Marie and Pierre Curie and applying it in Britain.

On his return to London he took up a lectureship at the Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden, becoming a professor in 1973. As a bedside clinician he was thoughtful, considerate, unhurried and insightful. For a junior member of the team, his ward rounds were a high point of the week.

Most unusually, each patient’s set of notes was annotated with hand-drawn illustrations to record what could not easily be set down in dispassionate clinical prose. Though in great demand as a speaker abroad, he was happiest with patients and staff on home turf, discussing the latest data and outlining yet more ideas for the next phase, never content to bow to accepted medical dogma.

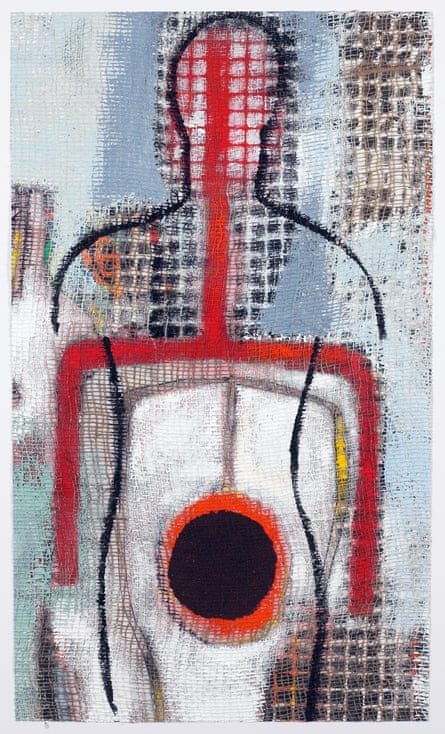

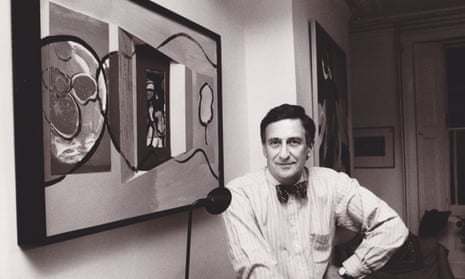

A keen artist, he had his first exhibition at Bangor University in 1962 and continued to paint and exhibit regularly, notably in Oxford, Edinburgh and London. In 2004, 35 of the small drawings made in his patients’ clinical notes were selected for the Royal Academy summer exhibition.

In 2018 he wrote in the Lancet: “When I decided to become a doctor, art and science were regarded as separate entities. I was already immersed in the arts and had doubts about continuing with medicine ... I made no distinction between a scientific and an artistic mind and I thought that the separation of artist and doctor was artificial.”

This belief ran through much of his output, and a collection of paintings and collages from 1963 to 2018 entitled Balance of the Interior (2020) was followed recently by Look Back at Now: Paintings from Isolation. It gave him particular satisfaction that three of his canvases are on show at the new headquarters of Cancer Research UK in Stratford, east London.

In 1958 he married the paediatric epidemiologist Catherine Stevenson King. She survives him, along with three sons and nine grandchildren.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion