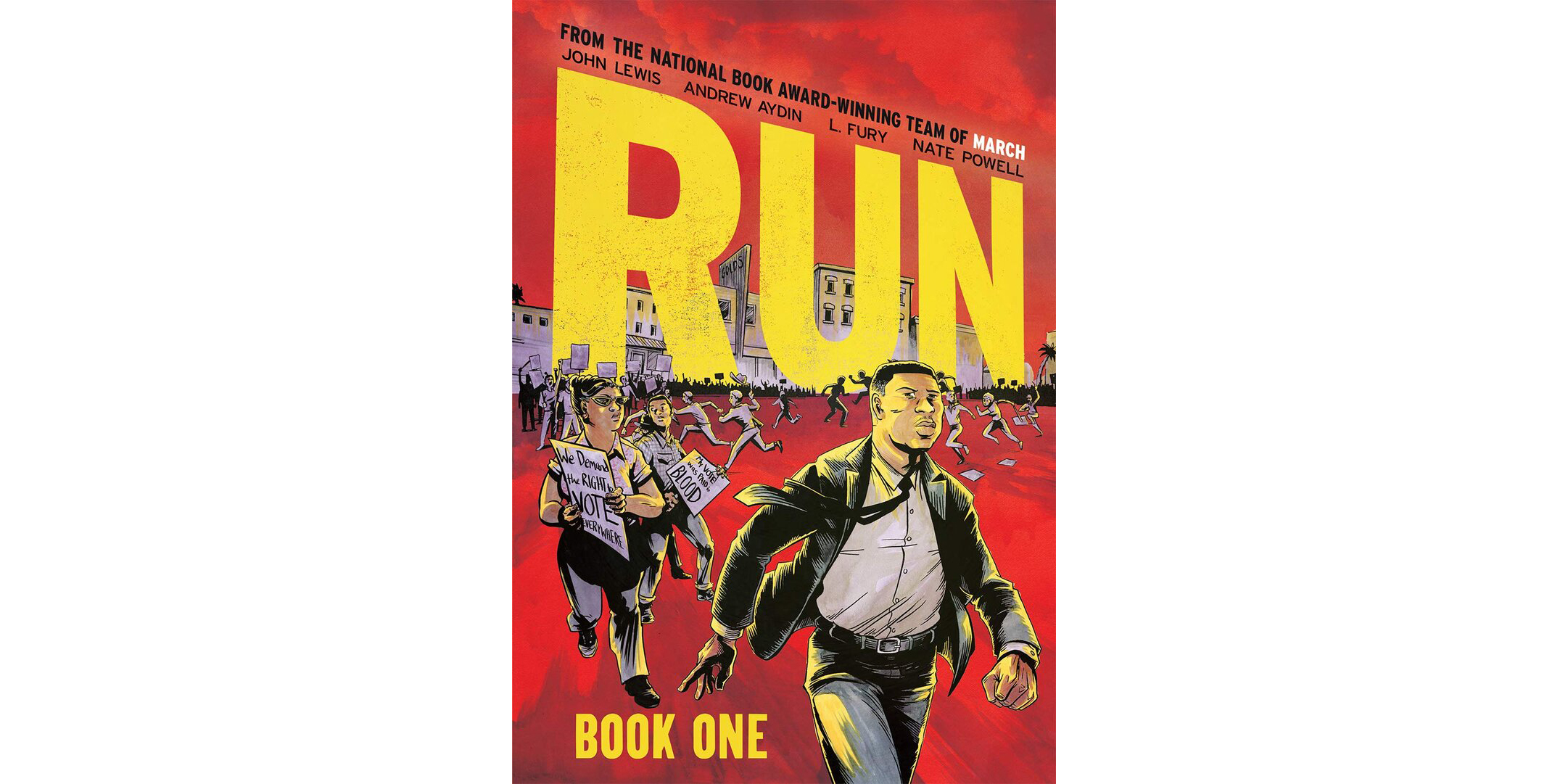

New Graphic Memoir, ‘Run’ Continues The Story Of John Lewis In The Civil Rights Movement

“Run” is the continuation of the life story of John Lewis.

Illustrated by Nate Powell

It’s a thorny task identifying modern American heroes, but few would deny Congressman John Lewis the honor. His courage helped lead the civil rights movement to its greatest successes, while he shared in the struggles of its toughest battles. He died of pancreatic cancer last year, but not before sharing his last story in “Run,” a graphic book co-written with his longtime aide Andrew Aydin and illustrated by Nate Powell. “Run,” a sequel to Aydin and Lewis’s previous trilogy work, “March,” follows Lewis’s period of activist work following the achievement of the Voting Rights Act, his later exit from the SNCC organization (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), and his relationships with fellow movement leaders. Aydin joined “City Lights” host Lois Reitzes to talk about his deep friendship with the congressman, his profound influence, and the extraordinary moments to which he bore witness.

Interview highlights:

The scope and stakes of ‘Run’:

“’Run’ begins two days after the signing of the Voting Rights Act…. John Lewis is in America’s Georgia, he’s protesting a church that’s refusing to integrate, and he ends up being arrested and going to jail. And that evening, the Klan holds their largest hooded march that they held in South Georgia in decades,” said Aydin. “It marked the moment where it became clear not only the forces opposing John Lewis in the movement, [but that] they were using the tactics of the movement against them, and they were engaging in an almost immediate pushback against the progress that the Voting Rights Act represented.”

“The people who were marching in that Klan’s march are people’s parents and grandparents. They are not so far removed from our day-to-day life, and we live with, not just the memories, but the echoes and the legacy of those actions in ways that are far more intimate than we’re often willing to acknowledge. These people are real people; these people are alive, these people are voting in Georgia right now.”

“With respect to John Lewis’s life, this is a moment that gets left out, because it doesn’t fit with a simple idea that he was a good man who always was working his way up; this is about setbacks. This is about facing, not just adversity, but failure, and losing. Being ousted as chairman, losing his organization, taking a moral stand against their own positions and resigning.”

On the process of collaborative storytelling with Lewis:

“John Lewis and I worked together for so many years and in so many ways, that we’d become incredibly close as collaborators. And one of the fun things about that relationship was that it allowed us to explore chapters of his history that I don’t think we’d have been able to explore otherwise,” said Aydin. “It starts with, actually, the newspaper articles from the South Georgia papers, and pulling out the quotes, and asking the congressman, then, ‘Do you remember this arrest? What did it feel like? What did it look like? Where were you standing? How did it happen? How did it unfold? How long was it before the police showed up?’”

“Even in the most difficult scenes, it was so fascinating to see him relive these moments in his mind. Because you’d bring him these primary sources, and you could just watch him go back in time and be there one more moment. Then you take all of it, and you put it into a script… and then our artist in that particular scene, who was Nate Powell, has to bring it to life.”

“It’s the collaboration that I don’t think many people get to experience, particularly not with someone of John Lewis’s stature. Because he was so open, and he was so kind, and he was so giving of his time, and he was so patient, and he really loved art. I mean, he loved art. And so this is something that brought him great joy, particularly in those last months of his life.”

Comics, an unsung medium of thought leadership in activism:

“Comics had been an integral part of the movement that had largely been overlooked. In 1966 you saw, as we depict in ‘Run,’ Jennifer Lawson and Courtland Cox actually used the Black Panther logo in one of its earliest instances in print, predating both the Black Panther comic book from Marvel, and also the formation of the Black Panther Party in San Francisco… Julian Bond made his own comic in 1966 as well, explaining his opposition to the Vietnam War.”

“I think the reason that the Congressman embraced it so whole-heartedly in the modern era… had a lot to do with the fact that this generation grew up on the internet, and he recognized that,” said Aydin. “This generation, growing up on the internet, their literacy is sequential narrative. A meme, or a tweet, these are sequential narrative forms just repackaged and put on the internet. And so if you wanted to teach them history, and you wanted to teach it to them effectively and quickly, you really needed to embrace the sequential narrative comic book format.”