September 10, 2001

The phone rang at 8:45 a.m., like it always did around that time.

“Morning,” I said, my eyes still closed.

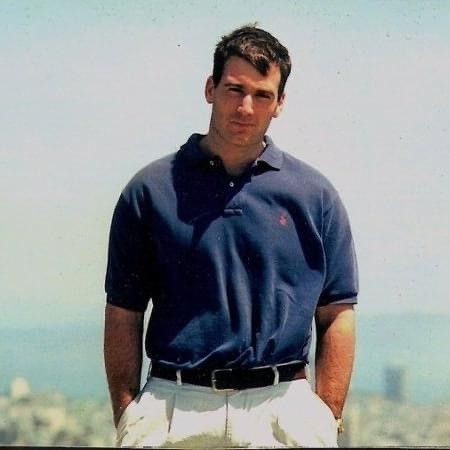

It was my twin brother, Jeffrey, of course. We talked every day. I say that without exaggeration. Every day. First thing in the morning, and then usually once or twice again later, checking in, keeping each other informed of the occasionally interesting experiences that made up our lives. We were 27.

He asked: “Are you up yet?”

I had been laid off from my job in July and had spent the summer looking for a new one, and he wanted to make sure I wasn’t slacking off. Jeffrey was not one for slacking off. And I wasn’t slacking off, but I was still in bed, wearing my Middlebury t-shirt. I went to Babson in Massachusetts, but I preferred my Middlebury gear. It was the shirt Jeffrey got me when he went off to school in Vermont, the one I wore to bed every night. The same one I’m wearing right now.

“Soooon,” I grumbled.

“What time are you going to the gym?” He put a little edge on this question, enjoying the nag. I could hear the familiar background noises of his office through the phone.

“Nine-thirty.”

He lived in New York, rooming with his best friend, Michael—since the three of us were in the ninth grade, he had been almost like a triplet to us. I lived in Boston, where Jeff and I and my dad had just spent the weekend for a friend’s wedding, a real family weekend, the best we’d had since our mom died three years earlier—warm late-summer sun, cocktails at my new apartment on Newbury Street.

I drove Jeff to the airport Sunday afternoon—not even fifteen hours ago—walked him to the gate and watched him board. I cried, because I’m like that.

“Then what,” he said. I pictured him twirling his hair at his temple, a Jeff habit.

“Then I’m going to the library to work on my job search.”

“Call me and let me know how you made out,” he said, gently now.

I rolled over, stretching, squinting into a shaft of sunlight. “I will,” I said. “Have a good day.”

“You too.”

“Love you.” I knew he wouldn’t say it back—no I-love-yous at work. That was our rule.

“Talk to you later.”

September 11, 2001

The ringing of the phone, same as the day before, same as the past thousand mornings. Jeffrey calling me.

“Morning,” I said, not yet caffeinated. It was 8:48 a.m.

“Don’t panic, I’m fine,” he said. I had no idea what he was talking about. “A commuter plane hit the other building.”

I bolted up in bed. It sounded like a local New York story, so I didn’t turn on the TV. I just listened to what he was telling me.

“Are you okay?” I asked.

He paused, then said, “Yeah, I’m okay, it’s just scary. I mean, the building’s on fire.” His voice, normally confident and all-knowing, wavered. I heard concern, which for Jeffrey came out sounding like he was annoyed.

“Are you being evacuated?”

“No, they said we’re safe. They said to stay on our floor.”

We talked a few more seconds and he said, “Let me call you back, I need to call Dad.”

“Okay,” I said, “Love you.”

I turned on the Today show, a split-screen of Katie and Matt with an image of the North tower on fire. I immediately called Jeffrey back.

“You need to leave!” I pleaded.

“I know,” he said.

“Good,” I said. “Promise you’re leaving?”

“I promise.”

“Okay, call me when you can. Love you.”

“I love you too,” he told me.

I called my father, who was sitting by the TV in my childhood home. I heard his breathing. We each recapped our calls with Jeff. We’d had almost identical conversations since Jeff had little information to share. As we were on the phone, we watched together in horror as Flight 175 crashed into my brother’s office building between floors 75 and 85. He worked on the 89th floor.

We hung up and I called Jeffrey over and over and over again at work and on his cell, work and cell, work and cell, work and cell.

Over and over and over.

October 2, 2001

My father and I had an 11 a.m. appointment with the head of Sovereign Bank in Wethersfield, Connecticut, the quaint, humdrum suburb where he and my mother had raised us. It was the first time in weeks that I was dressed in more than a t-shirt and shorts. My dad, always the dapper man, wore gray dress slacks and his blue-and-white–checked dress shirt.

We climbed into his two-door Acura, the one he bought after my mom died—he wanted something “sporty”—and drove in silence down Cricket Knoll, our cute street lined with houses I could see with my eyes closed; down Highland Street past the fields where Jeff played soccer and baseball as a boy while I sat in the outfield with my friend, picking grass, bored with the freedom of childhood; past the Kycia family’s farm stand, where we always bought our summer corn; over to the divided highway in the commercial part of town, where the bank was, the bank I’d never paid any attention to, the bank where we would now begin to build my beloved brother’s legacy, because my beloved brother was gone.

For weeks, we had hoped and prayed. Jeff’s friends in Manhattan would monitor the news for reports of those recovered from the wreckage. There would be a news alert that human remains—how many, the reporters didn’t know—were being taken to this hospital or that, and somebody would grab Jeff’s toothbrush or his hairbrush in a Ziploc bag and jump in a cab, rushing to the hospital to try to identify my twin by producing his DNA.

But this was rare. The hard truth that was emerging was that there wouldn’t be many remains at all.

Well before his time on Wall Street, before he even had a part-time job as a teenager with a landscaping company, Jeff made it known that when he was a grown-up—when he had money—he would use it to help people. He actually said he wanted to be a philanthropist, that it was his purpose as a human on earth. What teenager says that? He called it his grand plan.

Don’t get me wrong. Jeff wasn’t some self-serious do-gooder.

Well, he was that, actually. He got almost all A’s in school, including an A-freaking-plus in Japanese his first semester of college. (Over Christmas break that year, I asked him to teach me something easy. He said Japanese doesn’t really work that way, because it’s a complicated language. I pleaded: Just one word! “Fine: kame,” he said. “It means turtle.” I laughed and said that would made a great dog name. He rolled his eyes and not-so-politely disagreed.)

But he was also one of the most fun, intelligent, athletic, gregarious, interested, hilarious people you could ever meet. He could recite scenes from Top Gun on command. His favorite band was Rush, which was a little strange, but endearing. In high school, he used to drive around town pointing out the hedges he had trimmed in people’s lawns, perfect rows of perfect shrubs. He loved a Scotch after dinner and a punishing, invigorating run the next morning.

Once, a college friend had to travel to a hospital an hour away for some scary medical tests. Jeff not only loaned him his car, he showed up at his dorm early in the morning with coffee, drove him to the hospital, and stayed with him all day. He didn’t want his friend to have to go through that alone.

The bank manager, and the assistant bank manager, were waiting for us just inside the door. Wethersfield was a small town, and my dad and I were feeling as if we were recognized everywhere we went. The country was still reeling. There were fears of anthrax and subway attacks. That Ray Charles version of “American the Beautiful” played on every damn radio station every hour, it seemed. People stopped talking when we entered a room.

“We’re so sorry for your loss,” the manager said. Dad and I mustered polite smiles and quiet thank-yous and were escorted to a round table in a private area of bank awash in sunshine. I was exhausted and didn’t think I had the emotional strength, or even the physical strength, to have this discussion.

But we did it. In fact, I took the lead. It was no longer up to Jeffrey; it was up to me and my dad to fulfill the purpose of this person who was our everything: son, brother, protector, trusted advisor, voice of reason, best friend.

“My brother had dreams of helping people in need, and we’d like to look into a few ways we can do that in his memory,” I said. It was one of the first times I had spoken of Jeffrey in the past tense, and I wasn’t used to it. My voice was strong and I maintained composure. But as I spoke, tears fell from my eyes. The whole time.

“And we want to make sure we do it properly,” added my dad, finding his voice.

After about an hour at the bank—including about fifty-nine minutes of tears from me, my dad, the manager, and the assistant manager—we had created the Jeffrey D. Bittner Memorial Fund. Its focus would be quality education for those who otherwise couldn’t access it, something Jeffrey believed in. In the months before he died, he had begun volunteering as a mentor with Student Sponsor Partners, helping at-risk kids in New York City, having fun with them and helping them with their schoolwork.

I wanted to call Jeffrey and tell him the good news.

January 7, 2018

My birthday. Our birthday. It was a nothing birthday: 43. But it was the first birthday I spent with Chris, the man I had met on a blind date the summer of 2016, and with whom I had fallen in love. We went to the Capitol Grille in Boston with his father, his brother, and his brother’s fiancé. We made a toast to Jeff. We Facetimed Chris’s mom, who was in Florida. I drank my sauvignon blanc. And it was just so…nice. Like a real family birthday.

January 7 is close enough to Christmas that Jeff and I were always partly stuck in the post-holiday depression, but far enough into the new year that our friends and family could muster the will to celebrate.

As we got older, our birthday became the day that the timing of that first phone call mattered. Who would win the birthday phone-call race? Some years, I would pick up the phone to call him and somehow, he was already on the other end of the line. How does that happen? We chalked it up to our twin-telepathy.

What never changed was that it was our day—to celebrate each other, to celebrate the union that made us us. It didn’t matter who wanted to join our party. We were always a party of two.

That first one, in 2002, the only plan I had was to wallow in self-pity. It was barely light out, and silent. The phone didn’t ring—there was no race, no bragging rights, no gloating.

Then the phone started to wake up, as the rest of the world did. The calls didn’t have that cheerful, birthday tone.

“What are you doing?”

“Are you okay?”

“Do you have plans today?”

“How are you feeling?”

People seemed almost afraid to connect “happy” and “birthday” in one phrase. It was my birthday and there was nothing happy about it and no number of well-wishes, cards, gifts or offers to dinner would make this day anything other than what it was: the second-most painful day of my life, which I would now get to experience once every 365 days for the rest of my natural life.

Jeff’s girlfriend, Laurie, came to see me, along with his college roommate and his girlfriend. We had sushi, and an ice cream cake from J.P. Lick’s. We watched Ally McBeal. I told them about other birthdays:

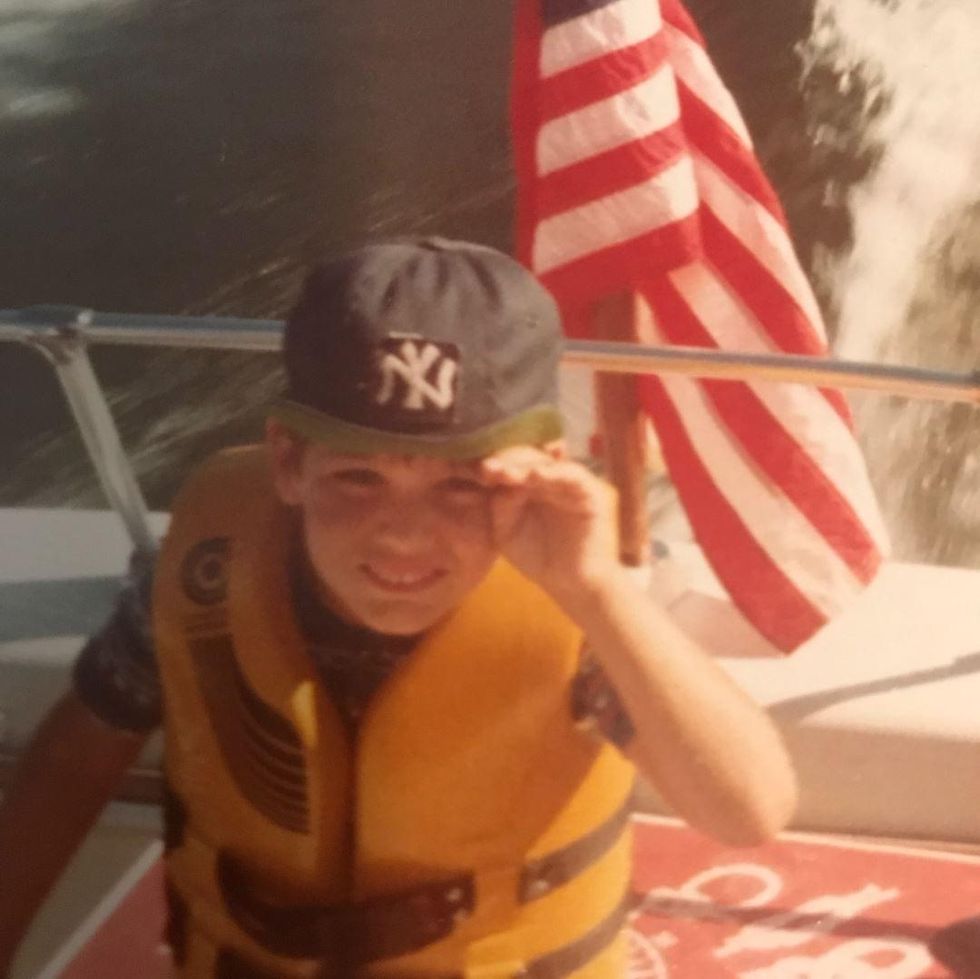

As kids, there was the bowling birthday, with a party at McDonalds after.

Our “grown-up” fifteenth birthday: dinner at home with twenty friends, after which we watched Eddie Murphy: Raw. We thought we were so cool, sharing this probably-inappropriate movie with our friends. Our mother, horrified, braced herself for calls from the other parents.

Our twenty-first, up at Middlebury with Mom and Dad and lots of friends, including Michael, who drove up from Connecticut, for a civilized dinner followed by our first beer run and too many shots of Southern Comfort.

Those memories made me feel closer to Jeff on our day when we could not be further apart. Over the years, our birthday has seen an evolution, of sorts. Instead of letting September 11 rob me of January 7, I’ve embraced our birthday as a way to celebrate Jeffrey and his legacy and our short but amazing years together.

These days I prefer to not recognize my age much, but I do look back at the year or the decade and think about how much my life has changed—and how much my brother has guided me along the way. All that stuff we used to talk about, big and small: what direction I should take my career, everyday decisions about vacations and credit cards, home purchases, the man I will soon marry…Jeffrey has influenced my every step both in life and after. This coming January 7 will be my twenty-first birthday without him. It’s impossible to believe that I have now lived almost half my life with him and half without him. Still, on January 7th mornings, I think of all the phone calls, and I think of this place I’ve gotten to now, and I feel comforted, loved, and, once again, whole.

Tomorrow

I wake up still half-expecting the phone to ring. I know it won’t. Jeff won’t be calling this morning.

But if he did? I think it would go something like this:

“Hello?”

“Morning. What’s going on?”

I take a deep breath. “Let’s see. Well, first: I’m getting married! Can you believe it? I don’t know when we’re going to do it, but it’ll probably be in Florida, or Boston, I don’t know. And—”

“Are you going to tell me his name?”

“Christopher. His name is Chris. And Jeff, I promise you would love him. He reminds me so much of you, but not in a weird way. He’s protective and kind, like you. He’s really close to his mother, which reminds me of you and Mom—that comforted me right away. He loves sports. He’s a gentleman. He’s got a quick wit and makes me laugh till I cry, daily—and he’s a saver! I knew you’d love that. I’ve never met anyone other than you who knows me better—better than myself. We talked about you on our first date. It was at Abe and Louie’s, on Boylston—you loved it there, remember? He had the filet and beer, and I had tuna tartare and a sauvignon blanc.”

“He had a beer with a steak?”

“He wanted something light! It was our first date. Anyway. He has a brother who’s like the little brother I never had, and soon I’ll have sister-in-law too, who’s amazing. His family is big and fun and loving and warm and they welcomed me with the most open arms you could imagine. I hit the in-law jackpot. I mean, after Dad died in 2004, I was a twin-less, parentless woman. I didn’t think I would ever have a family again. It took a long time. But then it happened. Better late than never, right?”

We’re both quiet for a moment.

“Jeff?”

“Yeah?”

“I don’t know how to tell you this, but Michael died. He had a heart attack back in December. He was 46. It was awful, just out of the blue one night.”

Another silence.

“How’s everyone?”

“You know. It’s hard. I talk to Ryan a lot. We’re part of this sibling club no one ever wants to be in. But we like to think you were there to greet him.”

“Pam.”

“Yeah?”

“How are you?”

Deep inhale. Right away I feel tears rolling down my cheeks. But my voice is strong.

“I’m good, you know? It’s taken a long time but I’m really good. I have a Yorkshire terrier, who you would love. Michael affectionately referred to her as my hamster.”

“What’s her name?”

I smile and say, “Kame.”

I feel him smiling at that. I go on:

“I love my job. I run big events for a non-profit, which I wanted to do ever since we started raising money in your name—you have quite a few scholarships in your name. Oh and a terrace.”

“A what?”

“Middlebury was building a new library, and all your friends got together and raised money to have the outdoor terrace named for you. I think because you spent so much time there. It’s called the Bittner Terrace.”

“That’s pretty cool.”

He’s quiet for a minute.

I’m quiet now too, which is unusual for me. And sniffly.

“You’re getting married,” Jeff finally says. “You’re going to have a good, long life. An incredible life. Live it. Okay? Promise me.”

I pause, look out the window at the perfect blue sky.

“I promise,” I say. We sit in silence for a minute. I bite my lower lip and wipe my eyes.

“Good,” he says. “Pammy, I love you.”

“I love you too.”