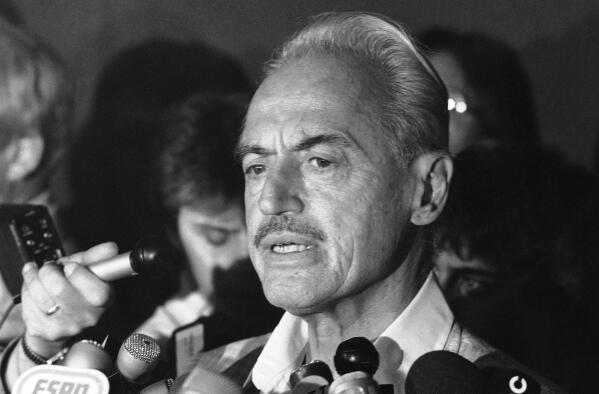

Marvin Miller remains “Godfather of it all” to modern MLBPA

Marvin Miller surveyed the baseball landscape and came to a radical conclusion: if ballplayers could be convinced to see themselves as blue collar laborers — not unlike the steelworkers Miller had once represented — there existed an opportunity to drastically shift the balance of power in the sport.

Miller’s 16-year tenure as executive director of the Major League Baseball Players Association included three strikes and two lockouts, a period of tension between management and players that introduced arbitration and free agency. The average big league salary rose from $19,000 in Miller’s second year in 1967 to $241,497 when he retired in 1982.

That number skyrocketed to a record of nearly $4.1 million in 2017, five years after Miller’s death. Yet, on the eve of Miller’s induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame on Wednesday, leaders of the current players association say his philosophies and strategies remain foundational pillars of the organization.

“The power and strength in unity,” MLBPA executive director Tony Clark told The Associated Press. “The importance of engaging and educating players, making sure that we have a respect for the sacrifices of those that came before us and what they endured. We learn to leave the game better than we found it.”

“He is, for lack of a better term, the Godfather of it all,” added Cardinals pitcher and association player representative Andrew Miller.

Few of the union’s leaders today had even passing interactions with Marvin Miller before he died in 2012. Even Clark, who began a 15-year career as a player in 1995, met him only in group settings a few times and never had a one-on-one conversation.

At the outset of a playing career that earned him over $22 million, Clark was educated on Miller’s approach to labor relations by veteran teammates like Cecil Fielder and Alan Trammell. Andrew Miller told the AP he got a similar set of lessons from coaches with the Florida Marlins when he played there in 2008. New York Yankees ace Gerrit Cole — an alternate pension committee rep — was even assigned book reports as a rookie by veteran catcher John Buck to ensure he understood the impact Marvin Miller and former player Curt Flood had wresting power away from once-domineering owners.

While Cole is planning similar class sessions with young Yankees players, he said that with baseball’s collective bargaining agreement set to expire after this season and tensions between players and owners growing after 25 years of labor peace, awareness of the union’s backstory is already high.

“In general, players are more educated now about what’s going on in the current atmosphere than certainly in the past, the recent past,” he said.

Marvin Miller had said that one of the greatest barriers for players when he took over the union in 1966 was exceptionally low morale after decades of stern governance by owners. He needed them to believe they had a path forward and to be unified in that faith, an area where his deft communication skills were crucial.

“I think the number one thing I see when I look back on it or when I read about it is his style of listening to players and his style of maybe guiding players to the right answer,” Andrew Miller said. “We are ballplayers. We’re not economists. We’re not labor lawyers.”

Marvin Miller, who had previously been the lead negotiator for the United Steelworkers of America, urged players to take on a blue-collar view of their labor situation. Of course, that was a different ask at a time when player salaries were just over 2 1/2 times the U.S. median household income. As of 2019, the players’ $4.05 million average salary was nearly 60 times the American household average.

That shift alone has presented challenges for association leadership. The 1,200-member MLBPA includes 15-year veterans with hundreds of millions in the bank along with players without a single day of service time who might still be going paycheck to paycheck. Where Marvin Miller’s task was instilling confidence in a cause, the modern union’s challenge is maintaining it across a wider range of factions.

In navigating differences between those blocs, Andrew Miller said he still tries to use the same blueprint laid out by Marvin Miller.

“That’s our job, those of us that have taken on the responsibility of taking one of these roles, is to make sure everybody feels like they’re being heard and listened to and being represented,” he said.

“At the end of the day, when you’re talking about a CBA or when you’re talking about return to play from COVID or something, it’s important to understand where your allegiances lie,” he added.

There is also respect for the boldness of Marvin Miller’s actions, like when he instructed pitchers Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally to play the 1975 season without signing a contract, setting the stage for a successful legal challenge to the reserve clause. He also oversaw the union through the 1981 strike, which led to the cancellation of 713 games. Resentment over those tactics is part of why it has taken so long for Miller to earn induction in Cooperstown.

“Inherently, there are going to be disagreements,” Clark said. “And as Marvin led the organization and as there were concerns that needed to be addressed, they lead to disagreements, both on the field and off the field. Those disagreements manifested themselves in ways where Marvin and others earned certain reputations.

“But at the end of the day, there’s no need to apologize for protecting and advancing the interests of your members, and that’s why Marvin never did.”

___

Follow Jake Seiner: https://twitter.com/Jake_Seiner

___

More AP MLB: https://apnews.com/hub/MLB and https://twitter.com/AP_Sports