For reasons sometimes beyond their control, musicians haven’t always been adept at protecting their business affairs. There are countless examples of unscrupulous deals, public fallouts (see Megan Thee Stallion’s recent spat with her label 1501 Certified Entertainment over a blocked BTS remix), music released without permission (Aaliyah’s back catalogue arriving on streaming services isn’t supported by her estate), and messy asset management. But the times, it seems, are changing.

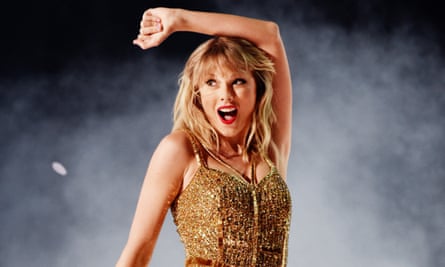

Recently, Anderson .Paak went so far as getting a tattoo asking for no posthumous albums or songs bearing his name be released. “Those were just demos and never intended to be heard by the public,” the ink reads. Lana Del Rey has said she has the same request written into her will. Taylor Swift is currently in the process of re-recording her first six albums, and therefore having total control of them herself, following a dispute with her former record label, Big Machine, who sold the master rights to the originals to mega-manager and Swift nemesis Scooter Braun.

This shift in consciousness is partly due to the power of the artist in the age of social media, and the availability of educational information on the ins and outs of the music business online. At the same time as both of these developments, it’s no fluke that the DIY music sector has been on a steady upward trajectory: in 2019, artists self-releasing took a 4.1% market share of the global music industry, up from 1.7% in 2015, according to Midia Research. Independent labels, artists releasing through flexible label services companies and the DIY market counted for a 32.5% share – higher than the income generated by the biggest major label, Universal. In response to the competition, and the possibility of being shamed on Twitter, it seems that exploitative contracts and practices are slowly improving.

As .Paak’s tattoo suggests, artists are also thinking about the quality of their legacy. Sometimes, rough drafts have an unpolished magic. Other times, demos remain demos for a reason. When artists die, and all the recordings are in the hands of a record label that’s keen to satisfy shareholders, carefully constructed careers can be tarnished. While rapper Pop Smoke’s posthumous debut, Shoot for the Stars, Aim for the Moon, received generally favourable reviews, hasty follow-up Faith was derided by Pitchfork as “unconcerned with anything outside of financial gain”.

In his recently published book, Leaving the Building, Eamonn Forde details the lucrative nature of artists’ estates along with the sticky results of disputes over control and non-existent, or dated, wills. The message is clear: organise your assets in life so that they’ll be protected, and respected, in death.