Anti-natalism has been making a bit of a comeback in recent years. It’s perhaps no surprise: gloom is all around, and gathering. But is being this much of a pessimist, this damned cynical, actually just pragmatism?

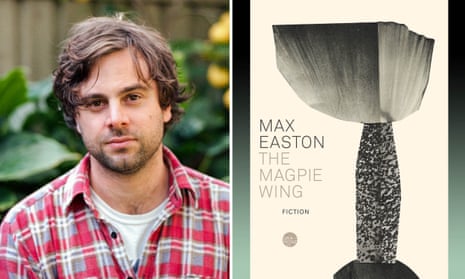

None of the three main characters in Max Easton’s debut novel The Magpie Wing are full-throated anti-natalists, but neither are any of them actively looking to procreate within the 25-odd years that the narrative spans. (Indeed, one of them goes firmly in the opposite direction.) What is true is that all three have been procreated, and because of this they struggle and sink. Perhaps in our current world, flailing and failing is a completely reasonable response.

The title of this original, exceptional novel refers to the wide western wing of Sydney: the sweep of suburbs that extend down and out, where the citizen-magpies of the city roost, and also root for their (now-merged) NRL team, the Western Suburbs Magpies. We join the three main characters, siblings Helen and Walt and Walt’s friend Duncan, in Liverpool and surrounds in the late 90s and early 00s as they spend their childhoods on rugby fields and at kitchen tables, before becoming more interested in drugs and sex and booze.

It’s regrettably unusual to see this area rendered in fiction, especially so well. It’s very welcome right now, as western Sydney grits its teeth through some of the strictest lockdowns in the country, and is basically being severed from the rest of the city – though really this has been happening for years. More publishers would do well to give better attention to the stories from the area – those talents you can see are waving, not drowning.

While Sydney’s west looms large for Walt in particular throughout his life, as adults all three grow weary of the suburbs, and are pulled east towards the city – specifically the chaotic music and even more chaotic dating scenes of the inner west. They fuck around and fuck around, only returning home once for a family Christmas party, ending up back at one of the dingy public parks snacking on crummy cocaine they’ve just stolen from Duncan’s dad, reminiscing about the good old days which were anything but. Plus ça change.

The Magpie Wing is at its best when things are happening, so it’s terrific that things are always happening in this book. Easton understands the adage that plot is character – and his characters are as real as any person you’ll ever meet. Walt, Helen and Duncan are Jenga towers built from dozens of flaws; each time a flaw is pinpointed and manoeuvred carefully out, they become even less stable. For years they pinball about the streets and suburbs of Sydney in sharp zigzags and slow parabolas, gathering in sharehouses, pubs, parks and public toilets, each trying to prove the validity of their own existence against convincing evidence to the contrary.

Duncan is your classic muted male – a lug of a league second-rower who laboriously crashes through packs on field, and who takes the same approach to all of life’s obstacles. His substance abuse and fixation on meaningless hook-ups only serves to point a bigger finger at his own repressive tendencies, ones he’ll never admit.

Walt is much spikier. Desperately disillusioned from day dot, he’s charged with an electric need to express his quibbles to all and sundry, grasping at one -ism or another for framework, including various kinds of anarchism and leftist punk-utopianism. He wants deeply to stumble across the solution to society’s ills – or even to compile it himself in one of his manifestos he scribbles late into the night and hides between books in op shops. That he is quite unable to see outside his own experiences and history is an apt metaphor for our age.

Helen is the most interesting of the three – I kept seeing a version of this novel that revolves only around her. She’s captivating as a narrative lens, reminiscent of Maria Griffiths from Imogen Binnie’s Nevada or Paul from Andrea Lawlor’s Paul Takes the Form of a Mortal Girl. Of course, Helen is ultimately doomed from the start by being the most intelligent, intellectually and emotionally, of her lot:

“Yeah, like I only know I’m depressed because my phone tries to get me to buy gym memberships. Or oversized shirts. Or pregnancy tests.” Helen thought for a second as the bleating of a pedestrian crossing had them walking further up the road. “It makes me feel like I’m being transcended.”

Extremely well-written are Easton’s long passages about music, with many different scenes of Walt and Helen listening to music, going to gigs, learning to play, rehearsing songs and sets, and performing – all among a heady culture of drugs, drink, love and sex. And this sex, and also sexuality – the two not always overlapping – is everywhere, often just for characters to try to lose themselves.

A bleakness that now seems common to younger contemporary fiction runs throughout The Magpie Wing, right to its denouement: the novel closes in 2021, in the middle of our pandemic, each major character descending deeper into either depression or mania, recognising the futility of doing much else. They’ve learned that the only constant in life is change – except change for these thirtysomething-year-olds has never resulted in a better situation. It’s very unfun being a millennial, especially this millennia, whether you’re fictional or real.

True Detective’s Rust Cohle says that “human consciousness is a tragic misstep in evolution.” In Easton’s The Magpie Wing, Helen, Walt and Duncan turn on and tune in, all whirring about for years and years, keeping busy with their pursuits and their causes and their responsibilities. And then as each of them grows old enough to inherit the pasts of their forebears and to develop pasts of their own, having tried to do various things that never pan out, they drop out, settling back to gaze at the light at the far-off end of the tunnel, wondering if the brightness has ever been anything but a train bearing down.

The Magpie Wing is out through Giramondo