God May Forgive Kanye West, but You Don’t Have To

On Donda, the rapper conveys all the imagery of surrender, but little of the weight.

To overcome what ails you, you must surrender. That is the third directive on the famous 12-step road map to sobriety and stability. Recovering from an internal battle that has had external repercussions means deciding “to turn our will and our lives over to the care of God,” according to the Alcoholics Anonymous guidebook, from which multitudes of 12-step programs—treating multitudes of psychological conditions—are modeled. God can mean different things to different people, but in AA’s original conception, the Christian god takes the burden.

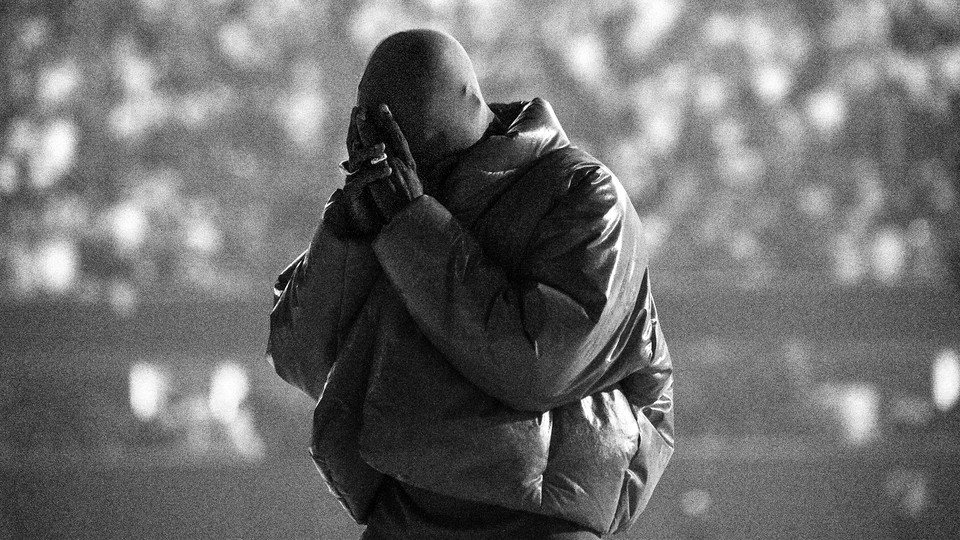

Kanye West’s Donda is the sound of such surrender. Ascribing that term to a 27-song album preceded by multiple stadium shows may seem strange, but the hype and grandeur surrounding West’s tenth full-length record highlight that he’s doing something pop stars don’t do very often: fall to their knees, declare existential bankruptcy, and ask for help. There is power—stirring power, ancient power—in that maneuver, and it electrifies some of Donda. But listeners may also feel a disconnect with the album that, West says, his label released against his wishes this past weekend (an unnamed label staffer told Variety that this accusation was “preposterous”). Across an hour and 49 minutes, supposed transcendence comes to feel suspiciously like regression, and surrender like self-exculpation.

The album punctuates an uneasy period for the rapper, who has bulldozed a highway through music, fashion, and politics for more than two decades. In the years after his 2016 album, The Life of Pablo—a chaotic opus about mental struggle—much of the cultural consensus around his value as a public figure began to dissipate. His music became patchier and less widely acclaimed; his oscillating Donald Trump support and presidential run threw off many fans; his mergings of art and Christian evangelism were sometimes cold and inaccessible. Then, in February, his wife, Kim Kardashian, filed for divorce—a development that seemed to confirm many of the anxieties over commitment, family, and fatherhood West had made central to his art all along.

Though known for his filibuster-style interviews and splatter-gun tweets, West has been strikingly quiet since the divorce news broke. Donda’s album art is a black square. Rather than promote it with interviews or speeches, he held three huge, ticketed listening events that felt more like art installations. In front of thousands, West patrolled around a bed, or glowered outside a barricaded house, wearing black clothes resembling commando apparel. He looked cagey, defensive, trapped—until he appeared to ascend to heaven on wires, or emerge from flames into a wedding ceremony. These stunts were simple, obvious, and mythic: Here was a warrior suddenly delivered into peace.

The record itself aches for such a miracle to unfold. After a serene intro of vocal chanting—the album’s title, his late mother’s name, said over and over—“Jail” uses jolting guitars and echoing yells to dramatize rock bottom. As West and Jay-Z twine metaphors about criminality with seemingly real details about marriage and sin, you’re drawn into the album’s narrative—but the effect, like much of Donda, works a little better as cinematic storytelling than as replayable music. The urgent rhythms of “God Breathed” continue the dire mood, and by the end of a multi-minute instrumental breakdown, longtime fans will be drunk with déjà vu. Chopped-up screams, industrial noise—early Donda resembles West’s divisive but great 2013 album, Yeezus.

Indeed, Donda’s sprawl comes off like an alternative-reality package of West’s greatest hits—or, to be harsher, a career’s worth of B-sides. After years of fans pining for the “old Kanye,” West gives them various versions of just that: The College Dropout goofiness on “Keep My Spirit Alive”; 808s & Heartbreak wistfulness on “Moon”; My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy’s swarms of guests and choirs throughout the track listing. Stylistic innovation has driven West’s career ’til now, but maybe he conceives of Donda as the album of his life—a capstone, an anthology. He might also be trying to steady his recent career wobbles by reminding the world of the sounds that made him famous. Regardless, most of these new songs would have been second-tier cuts on the earlier albums they evoke.

Donda’s highlights don’t match his previous heights, either—but they’re still pretty good. With crackling verses by Fivio Foreign and Playboi Carti and a detour into the rap subgenre of drill, “Off the Grid” joins West’s canon of classic crew anthems. “Believe What I Say” uses a Lauryn Hill sample and a house bass line to give anyone in a romantic spat something to strut to. “Heaven and Hell” repurposes a groovy ’70s sample for an eerie high. Most significant is a late-album run of gospel anthems: “Come to Life,” whose uplifting piano would be maudlin if it didn’t seem so hard-earned, and the epic “Jesus Lord,” which features testimonials about racial justice from West, the majestically verbose Jay Electronica, and the heartbreakingly eloquent activist Larry Hoover Jr.

Moments like “Jesus Lord” tie Donda to a larger social picture. But generally, the album revolves around West’s personal life. The specifics he shares about his marriage are haunting: “Sixty-million-dollar home, never went home to it,” goes one line. References to addiction, pills, and mental instability abound. So do proclamations of freedom and disses to people who are too “sensitive” to handle his truth. A story emerges about someone persecuted—by a romantic partner and by society—for being himself. West acknowledges that he’s made mistakes, but he doesn’t get into much detail about who wronged whom. Instead he sets up a struggle and simply, repeatedly, says God will fix it.

The history of worship music, which is to say a thick strand of the history of pop music, rests on the faith that—as Kanye’s mom says in one Donda interlude, quoting the poet Gwendolyn Brooks—“it cannot always be night.” But here, West expresses that faith in a way that curtails the momentum, complication, and depth that have marked his best work. It’s really not the listener’s place to quibble with his personal theology. But the searching and repentance that so much religion proscribes feel glaringly minimized here. “Alcohol anonymous, who’s the busiest loser?” he asks on “Hurricane,” but if he’s walked the latter parts of the 12-step journey—those that include making a list of one’s wrongs and hustling to correct them—he doesn’t spend much time sharing about them.

More unsettling: When West teams up with the abuser Chris Brown to rap lines like “I repent for everything I’ma do again” and “Last night don’t count,” it makes West’s conception of God—as a bail bondsman—sound anything but holy. At his third Donda release event, West brought out Marilyn Manson and DaBaby, both of whom feature on the track “Jail Pt. 2.” Manson has denied multiple women’s accusations of rape; DaBaby ended up deleting his apology for saying that people with AIDS are “nasty” (the defiance continues in his Donda lyrics). West’s alliance with such men could signal anything from full endorsement to a gesture of Christian forgiveness. He hasn’t really made a case either way, and his most notorious buddies certainly haven’t been seen working for absolution.

To be left wanting by a nearly two-hour-long album by one of the greatest exhibitionists in the world is not just odd. It’s exhausting. Inevitably and avoidably, Donda’s graceful moments will be outshone by spectacle and conflict. Despite West’s lofty pretenses, his friend Pusha T may have gotten it right in an Instagram post celebrating the album: “This is about power, money, influence and taste … nothing more, nothing less.”