During the extended stretch of Sunday afternoon that I spent straining to force myself to start listening to the way-overdue, yet strangely unexpected, release of Kanye West’s eleventy-dozen-hour-long album Donda, my mind kept wandering: What must it have been like, I wondered, to be a books critic during the time that Norman Mailer was regarded as one of the most important American writers? Here was a guy who, over the course of three decades, helped radically transform the practice of non-fiction, co-founded the culturally indispensable Village Voice, and led a charismatic, compelling public life. He was also a macho egomaniac, who wrote massively screwed-up things about race and feminism, was obnoxious and pugnacious, and, oh yes, was convicted of stabbing one of his six wives with a pen-knife in a drunken brawl. Now imagine being a newspaper book critic in the mid-1970s assigned to write about the new Norman Mailer book. You’d want to say, “Do we really have to give that son of a bitch the time of day, again?” But then again, that book might turn out to be The Executioner’s Song, the nonfiction novel that Joan Didion called “astonishing,” which helped reshape the debate over capital punishment in its time.

This, too, has been the Kanye Question for many years. As early as 2009, no less a master of rap beef than Barack Obama called West a jackass, a verdict the 44th president reconfirmed to The Atlantic in 2012. I always suspect this is a fundamental reason that an anti-Democrat grudge festered in West and bloomed into MAGA-hat-rocking Trump support, much the way Trump’s own political career was arguably directly caused by Obama’s zingers at the 2011 White House Correspondents’ dinner. (Maybe we’re better off when politicians are dull and humorless, causing fewer disastrous, sulky side effects.) Still, jackass-dom is so common among celebrities and often overestimated in its actual world importance. Also, for a long while, it was hard not to chalk some of West’s specific jackassery up to what emerged as untreated mental illness. Plus, of course, he was one of the most talented and influential creative forces in hip-hop, the definitive popular art form of the era. All of which remains true, although with album after album over at least the past five years, his creative vitality seemed to be diminishing in direct proportion to the embiggening of his jackassitude.

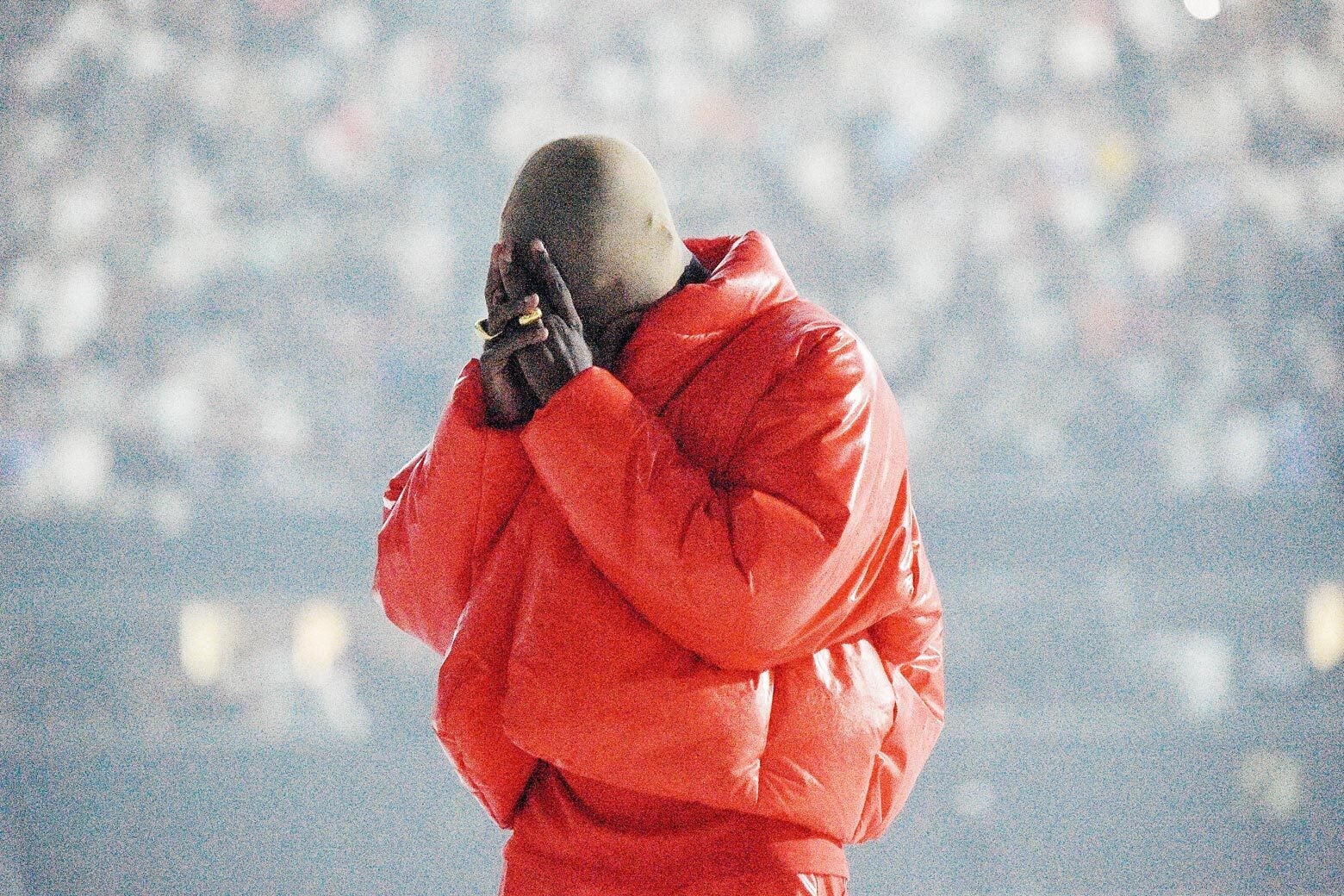

That feeling kept swelling throughout the so-called rollout of Donda, first promised last year and then hyped this summer with an ongoing series of lucrative livestreamed “listening parties” in the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta (where he took up temporary residency). These saw him mostly stalking silently around the arena floor with his face covered in a designer (and non-CDC-approved) mask, while the latest drafts of his songs played amid a smattering of theatrical flourishes. Each of these events was supposed to mark the eve of the album’s release. In each case, the album was not released. So far, so typical jackassomatic spotlight-seeking on West’s part.

But something snapped for me on Thursday night, during the third and as it turns out final listening party (in Chicago this time). West decided to invite out not only DaBaby, the 29-year-old Southern rapper who’s recently, rightfully been shunned by much of the music industry for making homophobic statements on stage that he’s refused to walk back, but also Marilyn Manson, the 1990s schlock-shock-rock singer now facing suits from four women as well as a police investigation for a long list of allegations of sexual assault. It soon became clear, with the premiere of a new version of the Donda song “Jail”—“Jail Pt. 2” on the album, that West brought these two miscreants aboard as fellow public figures persecuted by the politically correct mob, blah, blah, blah. Perhaps in the context of West’s latter-day turn to born-again Christianity, he also means to hold DaBaby and Manson up as sinners like himself, who need to be granted the compassion and redemption of God’s love; this is, after all, a running theme on Donda. I could almost sympathize with that. But in the counterbalancing context of Kanye West’s perpetual jackassaholism, and given the extreme provocation of these two choices compared to all the other fallen souls West could have selected to elevate, it’s hard to buy that any spiritual mission mattered to him nearly as much as the payoff in trolling—the points it scores in the never-ending game of Everybody Pay Attention to Kanye.

All of which made me not want to review Donda, especially when it was surprise-released not this Friday, as promised, or the next, but on one of the last beautiful Sundays of the summer. It was the day that both Lee “Scratch” Perry and Ed Asner died, so my sabbath could have been devoted to listening to some of the greatest dub-reggae sides in music history or bingeing old episodes of Lou Grant, the show that helped make me want to be a journalist in the first place and therefore led indirectly to the circumstances in which I was instead professionally obliged to listen to the latest output of a jackass. Not to mention that it was also the day a massively threatening hurricane was nearing New Orleans, on the 16th anniversary of Hurricane Katrina—the sort of event that a somewhat less-jackasstical Kanye West was once known to care about. Donda even includes a song called “Hurricane.”

Any such considerations, however, had to be put aside, because West’s on-and-off rival Drake had decided that he was going to release his own new album this coming Friday, so West had to “beat” him to market. There are lyrical references to this release-date conflict on Donda, right alongside those to eternal salvation. It’s dumb and crass, although exactly the kind of dumb and crass that West’s sputtering Midas touch often makes feel somehow smart and profound at exactly the same time—conveying the sensation that, yeah, that is how life is, at once a cosmic struggle against the existential void and a nonstop stream of petty irritations against some dude at work.

Which brings us back to the Executioner’s Song dilemma. Because I am also compelled to admit that on many levels, Donda is the best album that West has made in a half-decade. Which, granted, is not saying a lot. It’s spotty, lacking in range, monotonous in its tone and production techniques, and above all so obnoxiously longwinded as to display a total disregard for listeners’ limited remaining lifespans, with 27 songs that total an hour and 48 minutes. And the final four of those (taking up some 22 minutes) are just versions of earlier songs with some alternate guest features switched in, because West couldn’t make up his mind. But is it his first album since The Life of Pablo that totally convinces you it was made by the person who made The Life of Pablo? Yes, it is. It reintegrates the gospel tangent of his last couple of releases into the main line of his musical development, finding ways to be true to both sides.

That comes, to be clear, with a lot of misgivings. Besides the “part 2” versions (especially the goddamn DaBaby and Marilyn Manson one), there are at least a handful of songs that could have been jettisoned easily, like “Remote Control” (the Globglogabgalab bit is the only good part), recycled Pop Smoke track “Tell the Vision,” “New Again” (which, by the way, has goddamn Chris Brown on it), or the closing “No Child Left Behind.” The trap-beats-meet-organ-and-choir trick that dominates the music is effective, but not every version is equal. And in many other cases, a minute or two could have been edited out of the songs. While West’s attempts to bring dancehall artists onto a few tracks are interesting, Buju Banton sounds utterly out of place on the Lauryn Hill-sampling “Believe What I Say,” and outside of the chorus, a lot of what West does on that track could have used another draft too. Similarly, what dancehall singer Shenseea does on the outro of “Pure Soul” (otherwise a duo with Roddy Rich) is quite beautiful, but it extends the track way beyond its natural and most effective endpoint, where West declares (referring back to Yeezus), “This is the new me, so get used to me … Father, I’m yours exclusively/ Devil get behind me, I’m loose, I’m free.” And if it’s going to be a permanent policy for the now-devout West to blank out all the swears and n-words from his own and his guests’ tracks, just have the verses written clean to begin with; censored versions as the only versions are ridiculous.

Still, many of the tracks fulfill their potential here, like the original “Jail” with Jay-Z, as well as “Moon,” “Off the Grid,” “24,” “Heaven and Hell,” “Ok Ok,” and especially the lengthy storytelling centerpiece “Jesus Lord,” with plenty of the many, many guests outrapping West (whose flow is not at its best here, and its best has never been spectacular), but with his conceptual oversight making it all click together as per his better standards. Unlike many listeners, I also enjoy the sound-poetry/mantra-like “Donda Chant” that R&B singer Syleena Johnson opens the album with—consisting only of West’s mother’s given name repeated over and over, it was natural fodder for online mockery, but Johnson brings the variety and nuance it takes to carry this kind of piece off.

By contrast, West has now ruined the track that’s titled simply “Donda.” The sample of her voice there is still affecting, but West removed the verse he shared with Pusha T on an earlier version, where Pusha was (pardon the pun) pushing back on some of West’s dubious political and other choices. It was a dynamic highlight of the first livestreamed version. And it’s part of a pattern: If there hadn’t been a fan outcry, it seemed possible last week that West might have entirely switched out the original “Jail,” where Jay-Z is also lightly critical of him, for the new one with the two assholes. And one of the original tracks that’s disappeared from the final version is another that quoted West’s mother, called “You Never Abandon Your Family,” in which West excoriated himself for his part in the breakup of his marriage with Kim Kardashian-West to arresting emotional effect. What appears on the official release instead is “Lord I Need You,” a much more placid, self-satisfied, and all-round corny take on the situation. All these changes smack of emotional cowardice instead of the bold truth-telling for which West likes to congratulate himself and, sometimes, his sex-criminal friends.

So what are we left with after squandering the Lord’s sacred day of rest on an exhausting and dispiriting round or three of Everybody Pay Attention to Kanye? I guess at least enough evidence to say that hip-hop’s own Norman Mailer still has some of his old magic after all. And enough other jackglobglogabassery to make me wish he’d hurry the hell up and just lose it for good.