CDC, FDA, NIH—what’s the difference?

The U.S. agencies all play an important role in addressing the COVID-19 pandemic, but each evolved from a unique moment in public health history.

If you get confused by the alphabet soup of agencies managing the United States’ response to the COVID-19 pandemic, you’re not alone. NIH. FDA. CDC: What are their missions, and how do their roles differ?

Although the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) all respond to emerging and ongoing medical needs in the U.S., from infectious disease to mental health, they play different roles in fighting COVID-19 at home and abroad. And their mandates have evolved along with the nation and its changing public health needs.

A nation without public health surveillance

Healthcare wasn’t part of the plan when the U.S. was founded. At the time, epidemics were rampant and life expectancies low and the medical profession was not standardized, formally trained or licensed.

Although the government did carry out some public health efforts, it lacked a centralized health body and its actions were mostly on behalf of the military. In 1777, for example, George Washington instigated mandatory inoculation against smallpox for all Continental Army troops.

It would take almost half a century for modern medicine to emerge in the West, and for public health to become a national priority. As wars, contagious diseases like cholera and influenza, and unregulated foods and medicines threatened lives in the 19th century, several federal agencies tasked with improving and protecting public health were born.

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

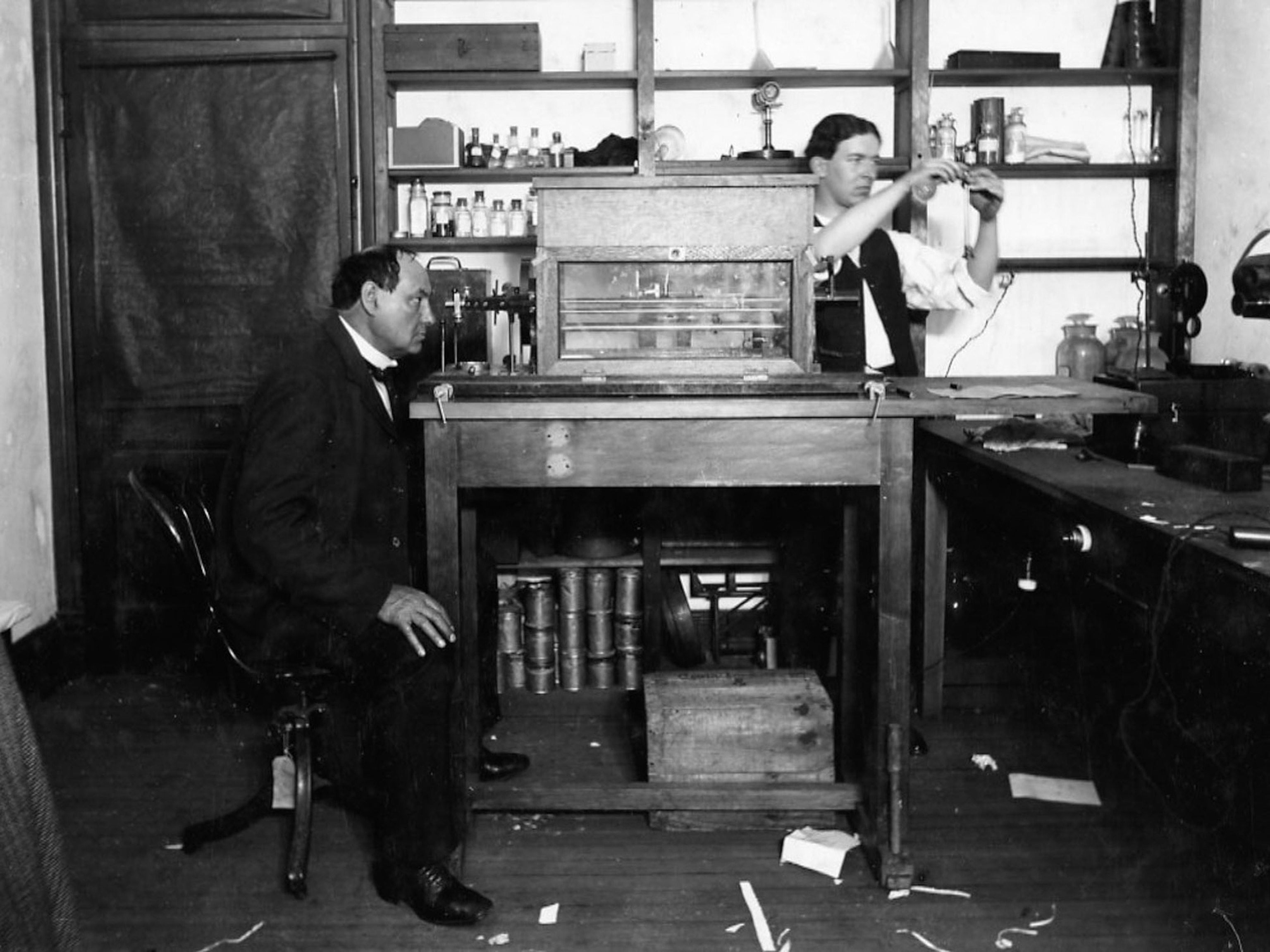

The U.S. government began its first investigations into food and other consumable products in response to a 19th-century wave of adulterated or counterfeit patent medicines and poisonous food additives. In the 1880s, Harvey Washington Wiley, a scientist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry—he was known as the “Crusading Chemist”—pushed for tighter regulations over food and medicine, even conducting highly publicized experiments in which he fed healthy men tainted food.

As a result of intense lobbying by Wiley and other reformers, legislators passed the Pure Food and Drugs Act of 1906, which made it a crime to sell adulterated or poisonous food or drugs. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Chemistry was tasked with regulation, and the Food and Drug Administration was born.

The agency, which gained its formal name in 1930, has a largely regulatory role in public health. It supervises drugs, medical devices, and clinical trials, and enforces the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.

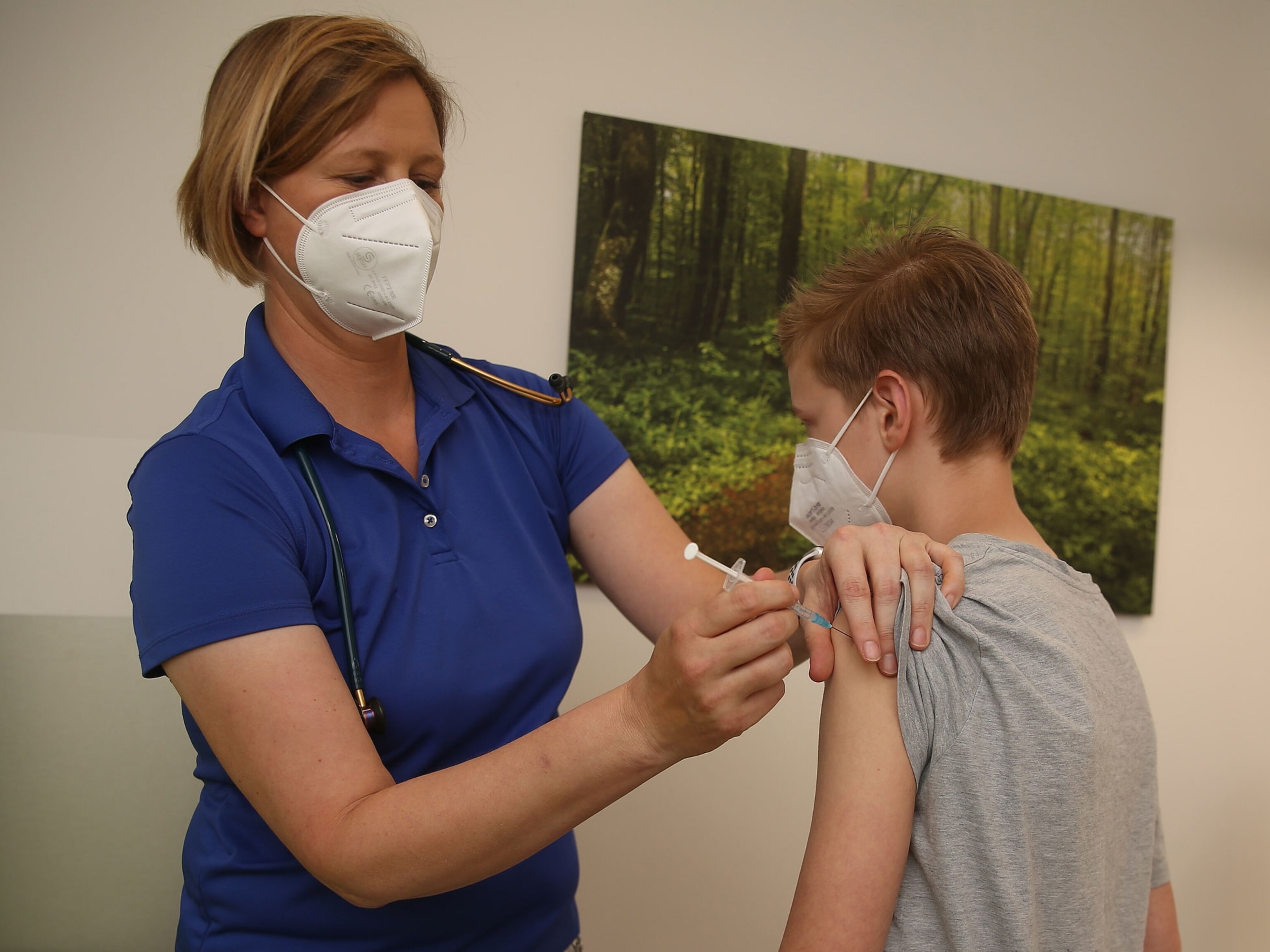

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the FDA has issued hundreds of emergency use authorizations, which speeds up the authorization process for drugs like vaccines and devices like masks. It has also taken action against pandemic-related fraud, issuing warning letters and fines and bringing cases against companies selling everything from fraudulent “medicines” to adulterated and unapproved tests for the disease.

National Institutes of Health (NIH)

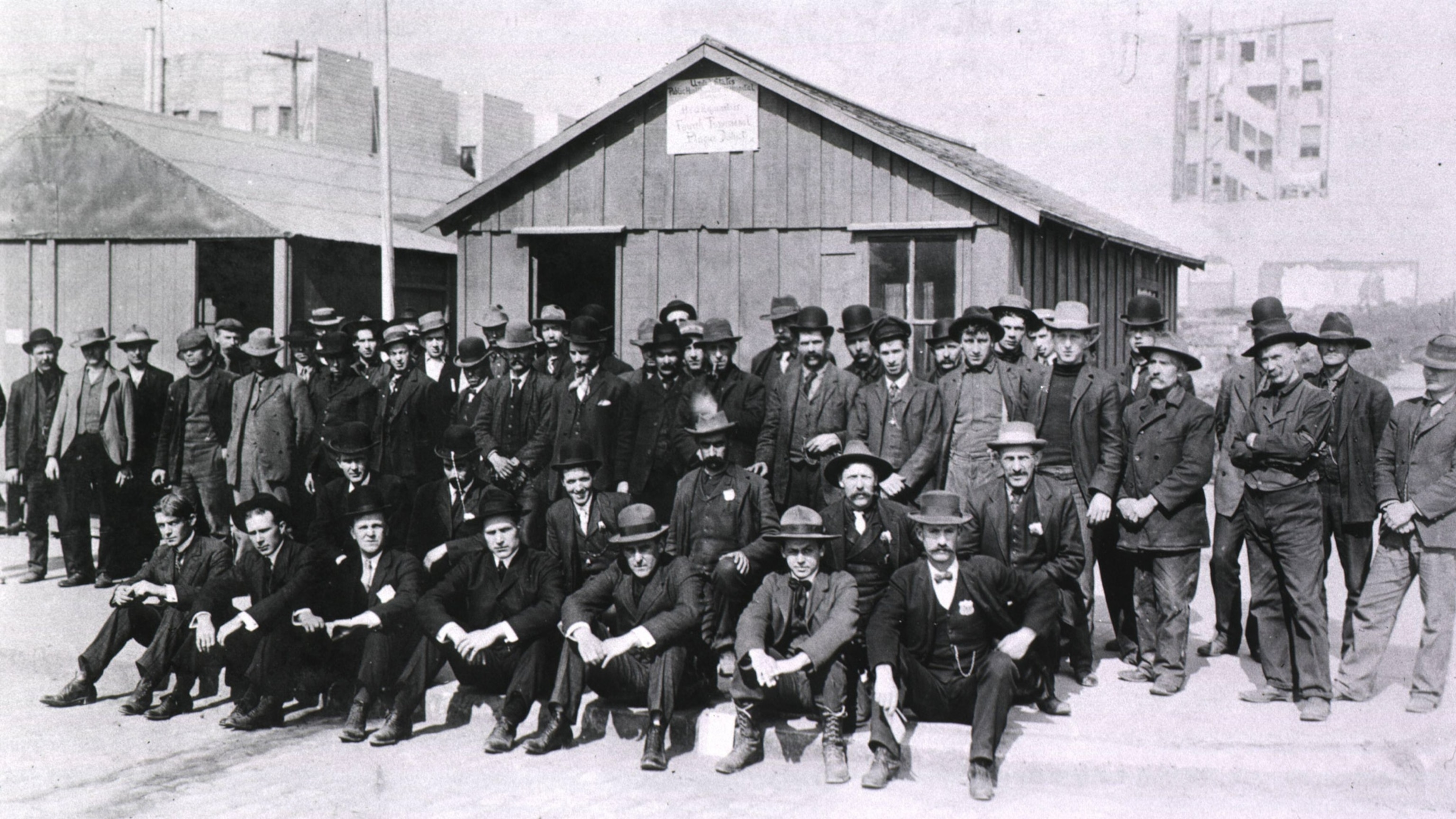

Another division of the Department of Health and Human Services, the National Institutes of Health has roots in the nation’s earliest health law, a 1798 statute deducting money from seamen’s salaries for medical care and hospitals. In 1870, the nation’s 31 marine hospitals were consolidated under the Marine Hospital Service (MHS) to create the Public Health Service, a commissioned corps of medical officers devoted to public health.

The MHS’s mandate ballooned in the late 19th century, when it took over the inspection of incoming ships and immigrants to U.S. ports. Tasked with examining passengers for signs of cholera and other highly contagious diseases and enforcing quarantines, its physicians became increasingly interested in the emerging science of infectious disease.

During subsequent health crises, the agency became more involved in medical research. It began to award research grants, and in 1930 changed its name to the National Institute of Health (the plural was adopted in 1948, reflecting the addition of research arms for everything from cancer to heart disease). Today, the organization has 27 different institutes and centers, including the National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Mental Health.

One of them, the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, led by Anthony Fauci, has been in the spotlight during the COVID-19 pandemic. The larger agency is approaching the disease from a variety of fronts and disseminating the latest research as it evolves. To date, the federal government has allocated nearly $4.9 billion to the NIH—funding earmarked for research on tests, vaccines, and treatments.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)

Although today it’s the most visible federal agency devoted to public health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has humble roots. It started out as the Office of Malaria Control in War Areas, an obscure branch of the Public Health Service founded in 1942.

At the time, malaria was still common in the South, where many military bases were located. The agency eliminated mosquito hotspots, trained local officials, educated the public, and developed malaria prevention techniques for troops deployed to the Pacific Theater during World War II. The initiative was so effective that, in 1946, a Communicable Disease Center (CDC) was opened in Atlanta.

At first, the organization was devoted purely to malaria prevention, and its efforts helped eradicate the disease from the U.S. by 1951. Then the CDC expanded, addressing everything from polio to rabies and becoming the official agency to deal with health in public disasters. Today, it’s the nation’s official health protection agency, tasked with informing the public, gathering statistics, detecting and responding to health threats, and eliminating disease.

During COVID-19, the CDC has developed tests to detect and monitor the disease, prepared guidance for public health departments and the public, directed money to healthcare facilities, and communicated with the public about every aspect of the pandemic.

Fighting COVID-19

All three agencies are part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, and their budgets grew with the pandemic. The CDC’s budget far outpaced the other agencies, though, reflecting the scale of both the pandemic and the agency’s national and global response.

But are the agencies prepared for the pandemic of the future? Not necessarily, experts say.

In an October 2020 report on pandemic preparedness, the Council on Foreign Relations, a nonpartisan think tank, called both the state and federal response to the pandemic “deeply flawed.” Without expanded investment in preparedness and a more coordinated response from the federal government, the report says, the nation won’t be able to face the unknown—but not unforeseen— public health challenges of the future.

“The virtual inevitability and high potential toll of future pandemics make investments in preventive and mitigatory measures both sensible and cost effective,” the report says. “The amount required to prevent and mitigate such incidents pales in comparison to their costs.”

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’How scientists are piecing together a sperm whale ‘alphabet’

- Orangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first timeOrangutan seen using plants to heal wound for first time

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- This fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then dieThis fungus turns cicadas into zombies who procreate—then die

Environment

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

- This floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on NigeriaThis floating flower is beautiful—but it's wreaking havoc on Nigeria

- What the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disasterWhat the Aral Sea might teach us about life after disaster

- What La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planetsWhat La Palma's 'lava tubes' tell us about life on other planets

- How fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitionsHow fungi form ‘fairy rings’ and inspire superstitions

- Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.Your favorite foods may not taste the same in the future. Here's why.

History & Culture

- These were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ eraThese were the real rules of courtship in the ‘Bridgerton’ era

- A short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looksA short history of the Met Gala and its iconic looks

Science

- Why trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve itWhy trigger points cause so much pain—and how you can relieve it

- Why ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevityWhy ovaries are so crucial to women’s health and longevity

Travel

- What it's like trekking with the Bedouin on Egypt's Sinai TrailWhat it's like trekking with the Bedouin on Egypt's Sinai Trail