You definitely know Phil Tippett’s work even if you don’t know his name. The 3D chess game in Star Wars, the AT-ATs and Tauntauns in Empire Strikes Back, ED-209 in Robocop, the bugs from Starship Troopers and the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park are just some of the creations Tippett has brought to life. One of Hollywood’s leading visual effects designers since the 1970s, Tippett has just spent three decades directing his first feature film: Mad God, a gruesome animated fable wherein a mysterious spy must infiltrate the lower depths on a dangerous mission. It starts with one of the shirtier quotes from Leviticus, the Bible’s angriest book, before plummeting to the depths of a gory, dripping underworld. Think Dante via Ren and Stimpy, or Pasolini with stop motion animation.

Mad God might be animation, but it’s not kids’ stuff. Tippett has just premiered it at the Locarno film festival, where he he sat next to a family. “Mum and dad and a couple of little kids, so I said to them: ‘I wouldn’t take my kids to this.’ They got up to leave a few minutes later. The mum said I was right. And I said, ‘It gets worse.’” Indeed, it does.

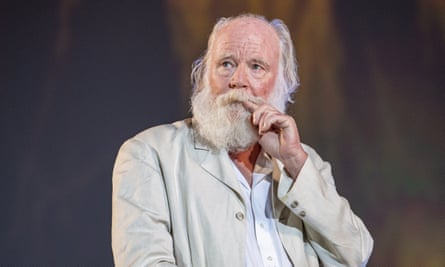

Meeting Tippett the next morning, he warns me that he gets memory blanks because of his medication. Wearing a black hoodie and sporting a white beard, he’s as avuncular as Santa but with the occasional glare of an Old Testament prophet. Like when I mention streaming platforms. “They’re evil,” he declares, then adding ruefully: “And they don’t even pay that much.”

Neither the streamers nor the studios wanted Mad God. A highly personal movie, it took Tippett 30 years to complete. “I shot the first few minutes many years ago on 35mm film, and then the project was too big in scope, and I lost my crew.” In the enforced hiatus Tippett concentrated on his day job. As stop motion effects (including “go motion”, as Tippett’s technique was named) were replaced by CGI throughout the 90s, Tippett had to concentrate on reinventing himself and the studio he set up. And yet, all the while, Mad God was gestating in the background.

“During that 20-year period I did all my homework,” he says. “When I was a young film-maker, Miloš Forman gave me the best advice I ever got, which was: ‘If you want to take a good shit, you’re going to have to eat well.’” So Tippett read Carl Jung, the Bible, Dante and did his research. He restarted work on Mad God when some of his colleagues at the studio came across the early footage and wanted to help. “These were the guys who grew up on Robocop and all of that stuff and that’s what they wanted to do: work with lights and models and tangible things.” When he gave talks locally, students would ask to work on the movie. “So on the weekends I would get as many as 15 and 20 people coming round. They didn’t all have the talent or skill, but I’d figure out the processes during the week. I had them do all the heavy lifting.” One short scene, he says, took three years to complete.

With no backing from the studios – “I didn’t bother” – the film was funded via a Kickstarter campaign. But despite the support he received, it began to take its toll. “I kind of became a method director and I just got totally lost. I hated working on it, and I just went down a rat hole of a psychic breakdown.” He’s not talking metaphorically. He ended up in a psychiatric ward for a week and was diagnosed with bipolar disorder (hence the aforementioned medication). Mad God – despite its radical nihilism – is a cornucopia of cultural references from the silent movies to Ray Harryhausen. “I appreciate silent movies a great deal. I believe when sound came it destroyed an essential part of the creative process of film-making.”

More recent innovations have left him less than impressed. “Everything’s gone in the toilet.” When I mention Avatar he shakes his head: “I’m not a big fan of that movie, or Jim Cameron movies, because he doesn’t have any humour. Even when he tries, it falls flat.” But his criticism of his own work is, if anything, harsher. “When I grew up it was like the wild west. No one knew what we were doing and so we were pretty much left alone. Everything became more corporatised over the years. I was like, ‘I don’t want to be doing this any more.’ Troopers was the last movie I was proud to have worked on and everything else was, ack, I’ve got to earn money.”

That’s a long stretch, I say. Starship Troopers came out 24 years ago. He shrugs. “Well, Miloš’ advice was the best advice I ever got … and kind of gave me the licence to eat well.”