The IRS Is Targeting the Poorest Americans

The agency doesn’t track the race of those it audits, but predominantly Black counties have higher audit rates than predominantly white ones.

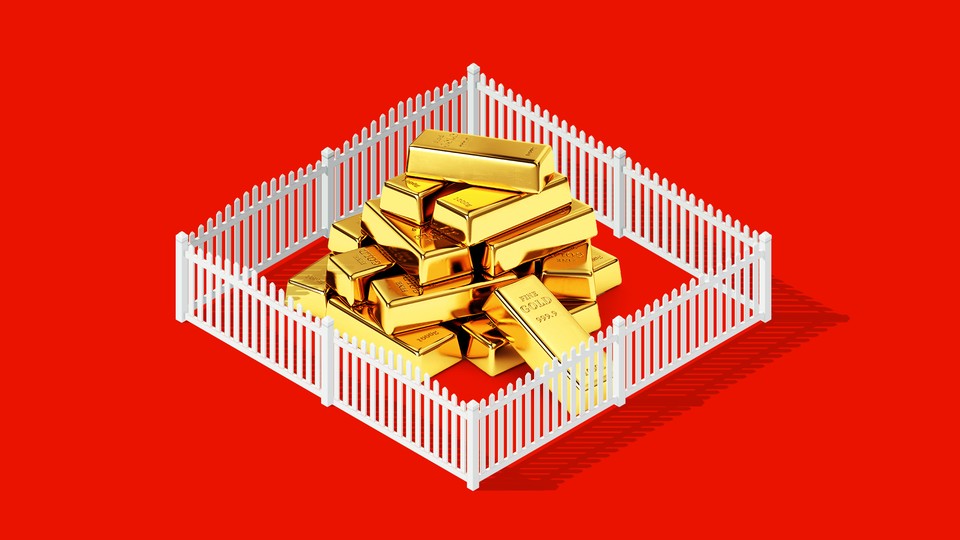

Senate Republicans recently killed a proposed increase in funding for the IRS that would have helped pay for the Biden administration’s infrastructure bill. The beneficiaries of that omission will be wealthy taxpayers, who regularly manage to stay just beyond the law’s reach with their tax-avoidance strategies. This is all too familiar. As my research shows, rich white Americans tend to get tax rules designed for their benefit. Quashing the funding that could have helped the IRS more aggressively pursue elite tax fraud is yet another example.

Without increased funding, the IRS will continue targeting low-income taxpayers for audits, particularly those claiming the earned-income tax credit. The EITC is a wage subsidy available to low-income workers. The typical EITC recipient makes less than $20,000 annually. In 2018, according to the IRS, the EITC lifted about 3 million children out of poverty.

But EITC calculations are extremely complicated, with a high error rate, in part because in 1998, Congress decided to increase audit funding instead of making the EITC simpler—a move that gained the support of then-President Bill Clinton, who viewed the increased audits as the price to be paid in order to keep the EITC. Today, EITC claimants are audited at a rate roughly equal to the top-earning Americans (1.4 percent versus 1.6 percent). The dollar amount of low-income Americans’ tax liability is negligible when compared with those making millions.

Moreover, while almost half of all EITC-eligible filers are white, an analysis by ProPublica found that the counties with the highest audit rates were “poor, rural, mostly African American and in the South.” Predominantly Black counties have higher audit rates than predominantly white ones because of the large number of EITC claimants living there.

If not for ProPublica’s reporting and the research of a former economist at the IRS, we wouldn’t even know this information. Last year, IRS Commissioner Charles Rettig told the Senate Finance Committee that he doesn’t tolerate racial discrimination and yet acknowledged later that the IRS doesn’t collect audit statistics by race. Research suggests that employers discriminate against applicants with stereotypically Black names, and the IRS has access to taxpayer names on tax returns. If Rettig doesn’t have the data, how can he be confident that the IRS is not discriminating on the basis of race when it comes to audits?

The IRS argues that EITC claimants are audited frequently because the audits are cheap to conduct, can be done by mail, and do not require a lot of IRS personnel time. Audits of wealthy taxpayers, by comparison, involve hand-to-hand combat with the best lawyers the wealthy can buy. It is simply easier for the IRS to go after the most vulnerable among us. The Office of Management and Budget, as directed by Congress under the Improper Payments Information Act of 2002, did put the EITC on a type of watch list of programs more susceptible to payments being improperly made. But while that ultimately led to increased audits in order to determine the extent of payments made in error, it did not control what the IRS could do with the rest of its audit budget.

Increasing the frequency with which the poorest Americans are audited, while not similarly increasing the rate of audits among the more affluent, serves to exacerbate America’s racial and class inequities. And the recent expansion of the child tax credit to low-income EITC recipients will lead even more Black families to be subjected to audits if the IRS continues its current practices.

As if this all weren’t bad enough, these audits have done little to reduce alleged tax fraud, a recent report by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found. The error rate on EITC claims remains high because the credit continues to be very complex. The solution is for Congress to simplify the EITC, not for the IRS to audit more people.

The fact that the government has taken the opposite approach is itself revealing. If you believe errors are inadvertent, then you reduce the complexity of the process. But if you believe errors are intentional “welfare cheating,” then you increase the rate of audits.

On January 20, President Joe Biden signed an executive order on racial equity that requires data sets collected by the federal government to be disaggregated by race. That order is the first step toward a solution: Only when the government starts tracking audits by race will it be able to address the biases in the system.

As I show in my book The Whiteness of Wealth: How the Tax System Impoverishes Black Americans—And How We Can Fix It, this is part of a much larger picture in which rich white Americans (and their allies in Congress) write tax rules to benefit themselves and harm Black taxpayers. When Black and white Americans engage in the same activity—marriage, homeownership, paying for college—tax policy results in white Americans paying less in taxes and Black Americans paying more.

Providing increased funding for the IRS to conduct audits is a necessary step toward a more equitable tax system. Rich white Americans should pay their fair share of taxes. The wealthy use the judicial system to enforce contracts that benefit them at the expense of others, they use federally supported transportation systems, and they use a host of other government services at disproportionate rates. But instead of paying up, they lobby members of Congress to rig the system in their favor, escaping the scrutiny of auditors. The ultimate lesson learned from the infrastructure package is that Republicans support defunding law enforcement—when wealthy, white taxpayers benefit.