The Fastest-Growing Group of American Evangelicals

A new generation of Latino Protestants is poised to transform our religious and political landscapes.

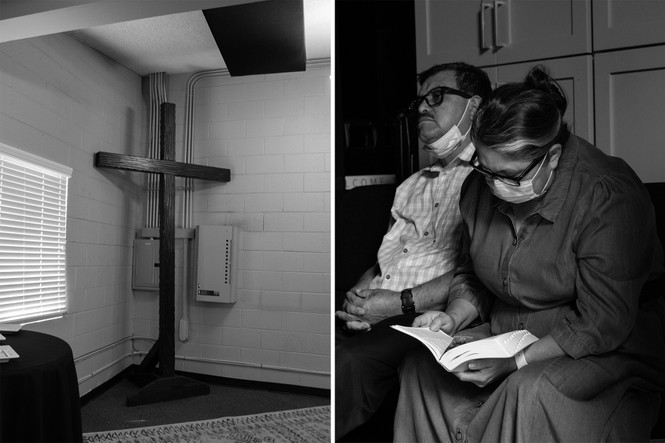

In 2007, when Obe and Jacqueline Arellano were in their mid-20s, they moved from the suburbs of Chicago to Aurora, Illinois, with the dream of starting a church. They chose Aurora, a midsize city with about 200,000 residents, mostly because about 40 percent of its population is Latino. Obe, a first-generation Mexican American pastor, told me, “We sensed God wanted us there.” By 2010, the couple had “planted a church,” the Protestant term for starting a brand-new congregation. This summer, the Arellanos moved to Long Beach, California, to pastor at Light & Life Christian Fellowship, which has planted 20 churches in 20 years. Their story is at once singular and representative of national trends: Across the United States, more Latino pastors are founding churches than ever before, a trend that challenges conventional views of evangelicalism and could have massive implications for the future of American politics.

Latinos are leaving the Catholic Church and converting to evangelical Protestantism in increased numbers, and evangelical organizations are putting more energy and resources toward reaching potential Latino congregants. Latinos are the fastest-growing group of evangelicals in the country, and Latino Protestants, in particular, have higher levels of religiosity—meaning they tend to go to church, pray, and read the Bible more often than both Anglo Protestants and Latino Catholics, according to Mark Mulder, a sociology professor at Calvin University and a co-author of Latino Protestants in America. At the same time, a major demographic shift is under way. Arellano, who supports Light & Life’s Spanish-speaking campus, Luz y Vida, told me, “By 2060, the Hispanic population in the United States is expected to grow from 60 million to over 110 million.” None of this is lost on either Latino or Anglo evangelical leadership: They know they need to recruit and train Latino pastors if they’re going to achieve what Arellano describes as “our vision to see that the kingdom of God will go forward and reach more people and get into every nook and cranny of society.”

The stakes of intensified Latino evangelicalism are manifold, and they depend on what kind of evangelicalism prevails across the country. The term evangelical has become synonymous with a voting bloc of Anglo cultural conservatives, but in general theological terms, evangelicals are Christians who believe in the supremacy of the Bible and that they are compelled to spread its gospel. Some Christians who identify with the theological definition fit the political stereotype, but others don’t. That’s true among evangelical Latino leaders too—they have very different interpretations of how the teachings of Jesus Christ call them to act. Every pastor I spoke with told me that they want to see more Latino pastors in leadership positions, and they each had a different take on what new Latino leadership could mean for the future of evangelicalism. When we spoke over the phone, Samuel Rodriguez, the president of the National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference and the pastor of New Season Worship, in Sacramento, California, told me, “We’re not extending our hand out, asking, ‘Can you help us plant churches?’ We’re coming to primarily white denominations and going, ‘You all need our help.’ This is a flipping of the script.”

Although Latino congregations are too diverse to characterize in shorthand, one of the few declarative statements that can be made about Latino Protestants is a fact borne out with numbers: They are likelier than Latino Catholics to vote Republican. The expansion of Latino evangelicalism bucks assumptions that Democrats and progressives will soon have a clear advantage as the white church declines and the Hispanic electorate rises. “Some counterintuitive things that have happened [in our national politics] would make more sense if we better understood the faith communities that exist within Latinx Protestantism,” Mulder told me over the phone, alluding to the differing perspectives Latinos hold on many issues, including immigration, and how more Latinos voted for former President Donald Trump in 2020 than in 2016. According to the Public Religion Research Institute, Protestant affiliation correlated more with Hispanic approval of Trump’s job in office than age or gender.

It’s difficult to know why exactly. Mulder speculated that many Latino Catholic traditions emphasize social justice, whereas Protestant theology in general tends to be more focused on a personal relationship with God and individualism, corresponding with Republican arguments about “personal responsibility,” which some Latino voters have said appeal to them. Rodriguez, who describes himself as a political independent but has both advised and publicly defended Trump, told me that Latino Protestant support for Trump was about abortion, explaining that he himself is an anti-abortion-rights “diehard.” Meanwhile, Elizabeth Rios—a Florida-based Puerto Rican pastor with Assemblies of God, a Pentecostal fellowship—told me that after prominent pastors such as Rodriguez aligned themselves with Trump, many Latino Christians, especially first-generation immigrants, trusted their judgment, because “they believe that God uses [pastors] as a mouthpiece.” Rios, who founded a small church-planting organization called Passion2Plant, which supports Black, brown, and Indigenous pastors who minister with an emphasis on social justice, thinks that many Protestant leaders have not done enough to disavow racism, and paraphrased the liberation theologist Willie James Jennings, who has said that white supremacy is a parasite and Christianity, its host.

Rodriguez and Rios are proof that there’s no monolithic Latino Protestant worldview, which is why it’s impossible to generalize about what the new Latino churches will be like—in worship style or political leanings or nearly anything else. Almost everybody I spoke with said that Latino, Latinx, and Hispanic are all unsatisfying terms: They rely on the false idea that there’s some fixed and universal pan-Latino identity, when in reality the wide range of people who represent Latinidad don’t come close to sharing the same history, let alone uniform tastes and opinions. “We as Latino people hold three different stories in our bodies,” José Humphreys, a second-generation Afro–Puerto Rican and the pastor and co-founder of Metro Hope Covenant Church, in Harlem, told me. “There’s African heritage, there’s Native and Indigenous heritage, and European. Those three stories ... manifest in different ways.”

Regardless of their ethnicity or country of origin, first-generation Latino Americans may be gravitating toward Protestant churches because they’re more likely than at Catholic churches to find Latino pastors they identify with. No one has a comprehensive tally of all the Latino pastors across the country, but less than 10 percent of Catholic priests are Hispanic, while a 2019 study of Hispanic Protestant churches found that 80 percent of Hispanic Protestant church planters are first-generation immigrants. “The biggest struggle of Hispanic pastors is being able to lead Hispanic families that have experienced racism and so many other injustices,” Arellano, the Luz y Vida pastor, told me. “You probably won’t be able to find a Hispanic pastor who hasn’t had someone in their church who’s had to go to immigrant court because they don't have papers.” As it reads on the website for Ministerios Oasis en el Desierto, a church in Phoenix founded by Rodolfo and Lucia Mendoza, Nicaraguan immigrants: “Solo imagine el dolor y los vituperios que tienen que atravesar los emigrantes en un país extraño y una lengua extraña.” Just imagine the pain and the vitriol that immigrants must go through in a strange country and in a strange language.

Those of us looking in can examine demographics or organizations, but for worshippers themselves the appeal is ineffable, emotional, and central to their life. Rios described how, as a teenager in the 1980s, she attended a church on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, then an epicenter of heroin use and violent crime. “At youth ministry, the fiery preaching reminded us that we were the apple of God’s eye and that we were meant for more. I was able to see myself the way God saw me,” she recalled. “That church became pivotal in the trajectory of my life ... I didn’t become a statistic.” Humphreys, who also grew up in Manhattan at the same time, told me, “The first-generation Latino Church taught me the power of community.” He remembered Afro-Latino pastors organizing drives to feed the hungry, visiting the sick, and setting aside time for people recovering from addiction to speak in church about their struggles. Still, no tidy description can encompass how millions of evangelicals find meaning and experience collective effervescence—that uplifting sense of togetherness people feel in a unified crowd—at church.

Latino outreach isn’t just an opportunity for churches—it’s a potential life raft. Increased religiosity among Latino Protestants is a crosscurrent: All over the country, the fastest-growing religious-identity group is what social scientists call the “nones,” those who don’t identify with a religion. Also expanding is the share of Americans who claim to have a religious preference but who don’t belong to a religious congregation. When we talked, Arellano repeated common wisdom among evangelicals that people unaffiliated with a church—the very people church planters most want to bring into the fold—are more willing to accept an invitation to a new church than a long-established one, one reason multiplying churches is a central goal.

The National Hispanic Christian Leadership Conference says it represents more than 40,000 churches, and Rodriguez told me it aims to plant another 25,000 before 2030. That goal includes independent churches as well as those connected to major Protestant denominations, such as the Southern Baptist Convention, which plans to help plant 1,000 new Hispanic-led churches in the next four years. Unlike during most of American history, when Christianity spread through a white-missionary model, the current effort is Latino-driven, according to Rodriguez. “We have the fortitude, the wherewithal, the drive,” he said. “We even have the financial resources ... It’s coming via the conduit of megachurches.”

According to the Hartford Institute for Religion Research, the median budget for a megachurch in the United States in 2019 was $5.3 million, almost all of which was raised from attendees. That means that megachurches and their networks, which are likely to be affiliated with conservative religious organizations, are far better equipped to finance new churches than smaller groups that provide seed loans to independent aspiring pastors, many of whom hope to attract 30 to 40 congregants in their first year. Rodriguez described how megachurches set aside a portion of their funds every month to invest in future church plants. He said each new megachurch plant within the NHCLC’s network has a three-year start-up-budget goal of $250,000 to $300,000, half of which pastors receive from within the network and half of which they must raise on their own by asking other churches and donors.

Outside the megachurch world, starting a church from scratch is usually financially risky, laborious, and emotionally demanding, so evangelicals have created numerous networks to help get new churches off the ground. Arellano, for instance, is also the executive director of Exponential Español, a group that provides training, advice, and liturgical and logistical materials to leaders of more than 15 Protestant denominations, and to roughly 2,000 individual Hispanic pastors who are scattered across the country. Exponential doesn’t provide funding itself, but it connects pastors with churches and groups that do—a lifeline for church planters who aren’t tapped into a megachurch network’s largesse and who are hoping to pull off a dream on a shoestring. Sponsor churches and other evangelical groups often provide seed money. The funds, though, are usually modest loans that need to be paid back, which puts pressure on pastors to attract congregants who can start donating.

Even as Protestant institutions are prioritizing Latino outreach, Latino church plants tend to receive much less financial support than Anglo churches. According to a 2019 study on Hispanic churches, Hispanic pastors of new churches said they received an average of $13,617 from outside sources, such as sponsor churches, in their first year, whereas church plants in general averaged more than $43,000 in their first year. Rios said that some of the same evangelical organizations that provide Latino pastors with fewer funds also prohibit women from leadership positions, and are bedfellows with the Anglo evangelical leaders whose support helped elect Trump. Rios, who described the Trump era as the “breaking point” that led her to form Passion2Plant, told me, “We keep repeating our patriarchal systems in our churches because of the money. At the end of the day, that is the power structure. Who has the money? … There’s such a hypocrisy and lust for power that so many Christians are terrible witnesses for Christ.”

While Rios wants Christians to have difficult conversations that push for systemic change in their churches and communities, she knows that kind of agitation isn’t what draws most people to church. She and other pastors told me that many first-generation immigrants in particular look to church for a refuge from the many stresses of their daily life, and they want community, not political controversy. Rodriguez told me that he never talks politics in church, adding that he believes the Latino churches are attractive to newcomers because, “whether it’s perception or reality,” they’re seen as independent, not affiliated with any party or ideology: “People want love, they want joy, and they don’t want to go to a church that’s CNN versus Fox.”

As the leader of the NHCLC, however, Rodriguez has steeped himself in politics. He’s served in advisory roles in the George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and Trump administrations. While Trump was president, Rodriguez appeared on several Fox News segments, including one in July 2019, soon after Homeland Security’s Office of Inspector General issued a report describing how Latin American migrants were held in squalid and unsafe conditions in at least five detention centers. Rodriguez told viewers that the White House had organized his visit to a detention center, and “I did not find deplorable conditions ... I found amazing people on both sides.”

When I asked Rodriguez whether he’d had concerns about appearing on Fox, he replied, “Quite the opposite. I think it was a gut decision, and it was strategic in nature. That gave me an entryway to interact with some of the Freedom Caucus members of the House and some very conservative members of the Senate, who were asking Samuel Rodriguez, ‘What do you propose?’ Samuel Rodriguez sat down in the White House with President Trump and Vice President [Mike] Pence, and literally in my hands I had a proposal.” He told me that he floated ideas for immigration reform, including a path to citizenship for many undocumented workers, a rare opportunity he said he had only because he’d done the Fox show. Rodriguez added empathetically that his conscience is clear, because the border agents he met—“not just random people, [but] people who attend churches that are connected to our networks”—swore to him in Jesus’s name that conditions in the detention centers were fine. “Never did I ever lose a member in my Spanish-speaking ministries because of my association with POTUS.”

Rodriguez went on to assert that because Latinos don’t easily fit into racial binaries, Latino evangelicals will have a unique role in repairing the nation. “We really do believe that the Latino Church will reconcile Billy Graham’s message with Dr. King’s march,” he told me, referring to the iconic televangelist who led crusades spreading Christianity around the world. “We really do believe it’s our prophetic assignment.” Humphreys, too, told me that he considers social action central to being a faithful Christan: “The church is at its best when it engages the culture, because that’s what Jesus would do. Jesus would dine with the people at the margins.”

It’s difficult to project with certainty how Latino pastors’ cultural or political engagement will transform what it means to be an American evangelical. What remains is the fact that millions of Latino worshippers look to their religious leaders for guidance on what to believe and how to act. And although the kinds of questions that Rios and her colleagues are asking have traction in a relatively small corner among Latino justice theologians, whether those ideas catch on within larger Latino Christian circles is to be determined. It’s possible that these theologians will help bring about a political realignment, and that in the not-so-distant future, references to “evangelicals” will conjure images of Black, brown, and Indigenous pastors fighting for equity. Right now, it seems likelier that, even as the Anglo evangelicals who have helped consolidate power for the GOP continue to diminish in number, their influence will outlast them, as Latino pastors in the churches they’ve helped plant come of age and speak to a new generation, fortifying conservative culture and political power.