Column: Fired from her hotel housekeeping job after getting COVID, she never lost faith

Margarita Santos was at home in Porter Ranch, cleaning the house she and four family members rent, when her phone rang early this month.

The last year has not been easy on Santos. In July 2020, she got fired from her housekeeping job at a Santa Monica hotel after testing positive for the coronavirus. But her fortunes were about to change. The hotel was under new ownership, and a union leader was calling to see if Santos wanted her old job back.

Yes, of course she did. Santos felt she had been wronged, but as a woman of faith, she’d never given up hope that justice would be served.

“I was very happy,” Santos said. “My brother and sister said, ‘Wow.’”

Her sister reminded Santos that it was a job she really loved. Not that she needed reminding.

“I said, ‘Yes, I do,’” said Santos, who might be the happiest hotel housekeeper I’ve ever met. It’s a physically demanding job, and the pay isn’t great, but she’s been bored in the past working jobs that don’t involve much exertion.

“I was so excited, I couldn’t wait to start,” Santos said.

She returned to work at the JW Marriott Le Merigot on July 13.

So why exactly was she fired in the first place, and why was she brought back?

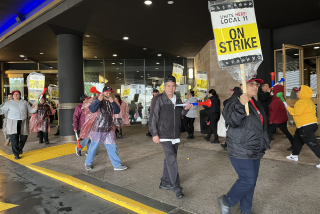

I first met Santos almost exactly a year ago. She was feeling better after her bout with COVID-19, and she had joined a demonstration organized by Unite Here Local 11, aimed at getting her job back.

Community leaders marched in front of the hotel, and Rabbi Neil Comess-Daniels led a prayer and carried a sign that said “Bring Margarita Back.” The rabbi told me he was there because the community had to show support for low-wage workers hit hard by the pandemic.

“At a time when I needed them to help me,” Santos said of her employer when she addressed the demonstrators that day, “they let me down.” And she wasn’t the only one in her house to get sick. A brother, sister and niece also got COVID-19, Santos said.

As I reported a year ago, Santos had a headache one day and informed a manger, who told her to take some painkillers. She did, and kept working. A few days later, she felt ill again at work and was sent home. She went and got a coronavirus test, and Santos said that as soon as it came back positive, she called and told her manager but didn’t hear anything back.

A few days later, Santos got a termination letter claiming she knew she was sick but went to work anyway.

“You knowingly put our guests and your own co-workers at considerable risk of being infected with COVID-19,” her boss wrote, accusing her of “egregious behavior and conscious disregard.”

Santos was shocked by the accusation and wondered whether she’d been targeted because she had been a union organizer for Unite Here, which has been negotiating a bargaining agreement with the hotel for five years. The hotel manager at the time told me he had nothing to add to what was in the letter Santos received.

Santos had a lot of experience, having worked at Le Merigot for nearly a decade, but the entire hospitality industry was pummeled by the pandemic, so she couldn’t just move to another hotel.

Kurt Petersen, co-president of Unite Here Local 11, told me the union has 31,000 members in California and Arizona, and 90% of them lost their jobs. Things have gotten better, with 40% of them back to work, but Petersen said many are working fewer hours than they did previously.

With a new strain of the virus threatening more progress, and some hotels eliminating daily room cleaning, Petersen said a return to pre-pandemic days could still be a long way off. Unite Here has joined with Clergy & Laity United for Economic Justice on a fundraising campaign, at cluejustice.org, to help those who are struggling.

Santos didn’t let her misfortune idle her entirely. She had once worked as a seamstress, so she began looking for customers who needed alterations, and some of her new clients included Le Merigot co-workers who wanted to help her out. She also had some experience as a hairdresser, so she got out her clippers and went to work.

But keeping busy didn’t erase the sting of her firing.

“It was a difficult year,” Santos told me. “I cried … and it was very depressing.… I wasn’t mad, I was resentful…. For me to lose my job like that, after I gave a lot of my life to that place, just wasn’t fair.”

She also lost her healthcare plan, Santos said. She signed up for unemployment benefits and Medi-Cal, but as she recovered from COVID-19, she had medical expenses that weren’t covered. And she still has symptoms she thinks are left over from her bout with the virus, including occasional chest pain, which wasn’t there before, and something her doctor called “brain fog.” She’s relieved that she’s now vaccinated.

In March, Le Merigot was sold to Stockdale Capital Partners. Petersen says Unite Here brought up some unresolved issues between management and employees, including the case of Santos. Bill Doak, managing director of hospitality for the new owners, told me he recalled reading about Santos in my column last year.

Doak said that as the pandemic raged last year, it made for a difficult and scary time in the hospitality industry. He said he didn’t know the entire background of the Santos termination, but he asked his new management team to review the situation and see whether anyone would object to bringing her back.

“It’s good for business to do the right thing in this situation,” said Doak, the son of a minister.

I told him Santos is religious and had hoped for a Le Merigot miracle.

“She had the support of co-workers and the union and had a good record,” Doak said. “As to her point about having faith, she clearly was a good employee, and her past history demonstrated that.”

Petersen said the new owners seem generally more sympathetic than the previous ones to the workforce, including Santos.

“Kudos to Bill and his company, because they didn’t hesitate when we raised her situation,” Petersen said. “They said, ‘You know, that didn’t sound right that she was let go and we’ll bring her back.’ And they did.”

Santos met me in the lobby of Le Merigot on Tuesday, just before her 2:30 p.m. shift. She said she hadn’t done all the necessary paperwork yet, but she understood she’d be making about $17 an hour, a raise of 75 cents, and get her benefits back, too.

She punched in down in the basement, where she bumped into colleagues she hadn’t seen in a while. One of them, a woman named Claudia, said everyone was excited to see her back on the job.

A housekeeping call came in from the sixth floor, where a guest needed a set of towels.

Santos was on it in a flash, riding the service elevator and making the delivery, happy to be back.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.