Miles Davis takes a bow on new 1991 live album; Harold Land is ‘Westward Bound’; and Jen Shyu sings of loss

Three new albums, two of them released posthumously, provide aural treats and some surprises

Miles Davis, “Merci Miles! Live at Vienne” (Warner Records/Rhino)

An aura of mystery and intrigue, on stage and off, were constants throughout the extraordinary career of Miles Davis.

The legendary trumpeter, composer and band leader created transcendent music that profoundly inspired countless jazz artists, along with everyone from Joni Mitchell, Prince and Radiohead to Mos Def, John Legend and John Mayer.

Or, as Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood put it in a 2001 Union-Tribune interview: “Discussing Miles makes you feel like a dime store novelist talking about Shakespeare. ... We’ve taken and stolen from him shamelessly, not just musically, but in terms of his attitude of moving things forward.”

Indeed, Davis thrived by repeatedly defying expectations — and by pushing himself and the members of his various bands to explore, take risks and reach for new heights.

Except, that is, when he didn’t, which was the general rap against him for much of the final decade of his career. His embrace of contemporary funk and R&B in the 1980s did not sit well with some longtime fans. Neither did his newfound penchant for recording with drum machines and synthesizers, which gave his music a slick, sleek, pop-friendly sonic sheen.

With “Merci Miles! Live at Vienne 1991,” listeners can judge for themselves. The two-CD set is by turns fascinating and flawed, sometimes concurrently, for precisely the same reasons.

“Merci Miles!” was recorded at a festival in France on July 1, 1991, less than three months before Davis died in Los Angeles from a combination of respiratory failure, pneumonia and a stroke. At 65, he had irrevocably changed the sound and shape of contemporary music several times during his storied career, which saw him do his first recording sessions in 1945 while still a teenager.

Davis went on to pioneer an array of jazz styles, including cool, hard bop, modal and fusion. He also nurtured an array of budding young talents who became legends in their own right, from John Coltrane, Bill Evans and Wayne Shorter to Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea and Keith Jarrett.

No one in the band Davis led in 1991 has since risen to the level of his famed previous collaborators, although saxophonist Kenny Garrett now has at least 19 solo albums to his credit. But the well-drilled quintet featured on “Merci Miles” is notable, if more for its turn-on-a-dime ensemble work than as a vehicle for transcendent solos.

Listening as intently as it played, the band was very well attuned to its leader’s finely calibrated shifts in tone, intensity and direction. Their pinpoint dynamic control is showcased throughout this nearly 80-minute recording, on which the presence of the already ailing Davis is felt as much as heard. While his periodic visual cues to his fellow musicians can’t be seen here, the group’s flexibility and cohesion as a unit is unmistakable.

Witness the 18-minute version of Michael Jackson‘s Top 10 1983 hit, “Human Nature.” Davis, playing muted trumpet, quickly dispenses with the silky melodic theme of the original. The song is then transformed into a fervent, rhythmically propulsive work — enhanced by Moorish and Eastern African flavors — that all but boils over. Davis’ exquisitely subtle trumpet solo on “Human Nature” at times evokes the richly melancholic textures of his 1960 classic, “Sketches of Spain.”

“We respect a song so much that we will add to it,” Davis told me in a 1985 Union-Tribune interview. “If I can’t add to it, I won’t play it.”

True to his word, he plays extemporaneously for 3½ minutes at the start of his remake of Cyndi Lauper‘s 1983 chart-topper, “Time After Time,” before breaking into the first verse and chorus. Clocking in at nearly 10 minutes, “Time After Time” features Davis from start to finish. His whisper-soft trumpet work is a master class in nuance and restraint. So is his impeccable use of space and the silences between notes, a musical trademark throughout his career.

Equally notable are the serpentine unison lines he plays with Garrett on “Wrinkle.” Davis and his band throw down the funk on the Prince-penned “Penetration” and dig deep into the blues on another Prince number, “Jailbait.”

Davis often cedes the spotlight to Garrett, keyboardist Derron Johnson, former Trouble Funk drummer Ricky Wellman (now deceased) and dual bassists Richard Patterson and Joseph “Foley” McCreary, Jr. But at the time of his final tour in 1991, the trumpeter knew his health was declining, and — with it — his stamina.

Happily, when Davis does play here he does so resolutely and with palpable passion. Like an aging prize fighter, he skillfully times his musical punches, imbuing each sonic move and gesture with unmistakable purpose.

What results is not the artistic swan song that Davis 1991 live album with Quincy Jones, “Miles & Quincy: Live at Montreux” — recorded exactly one week after this Vienne performance — represents. But as a welcome documentation of a graying icon steadfastly looking forward, not back, “Merci! Miles” is as welcome as it is well-titled.

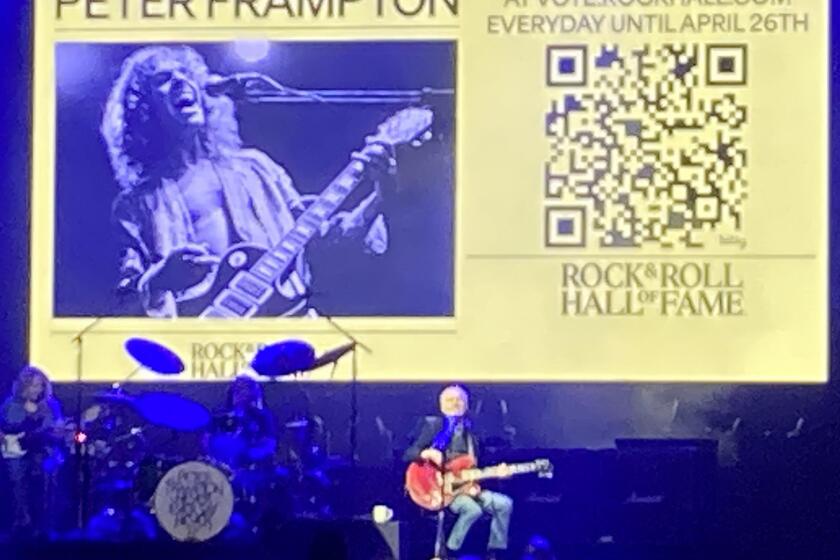

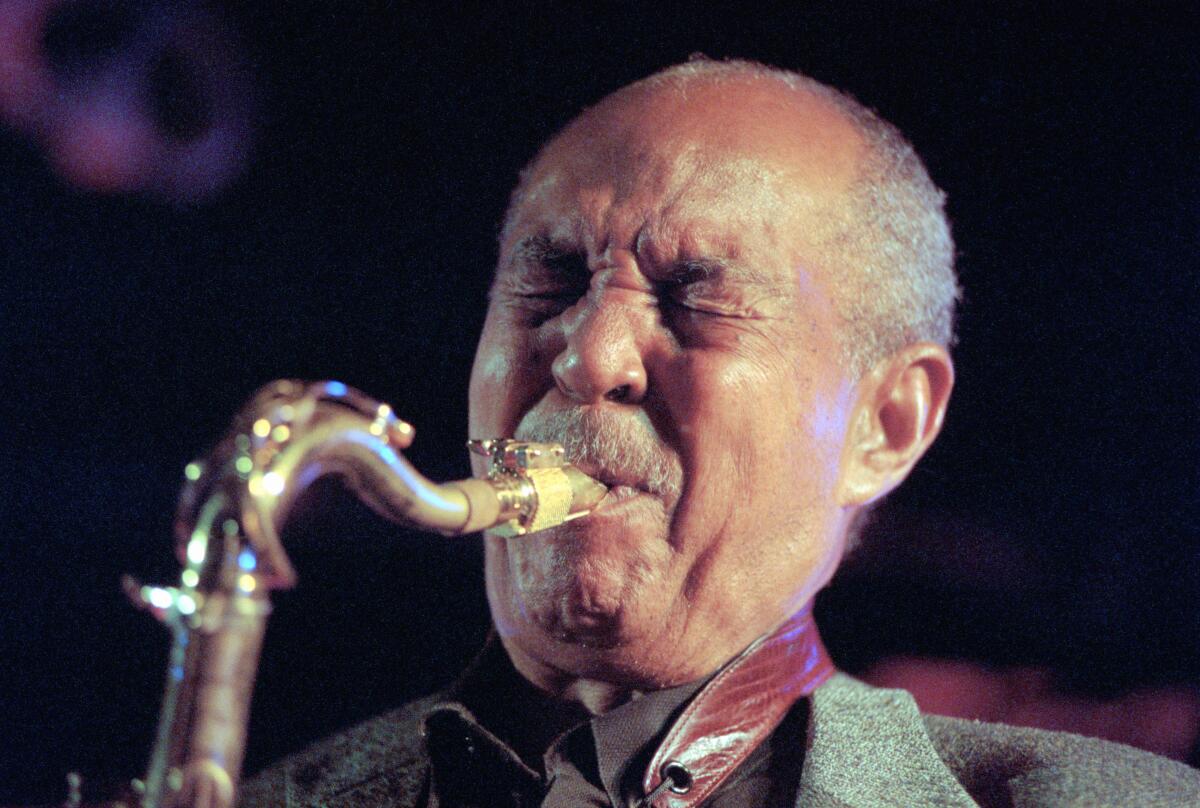

Harold Land, “Westward Bound” (Reel to Real)

San Diego-bred tenor jazz sax dynamo Harold Land was in his early 30s when the first three of the eight songs on “Westward Bound” were recorded in 1962 at The Penthouse, a Seattle nightclub.

The other six pieces were recorded at the same venue in 1964 and 1965. Each demonstrates the admirable balance that Land — who was 72 when he died in 2001 — achieved as a potent hard-bop saxophonist whose playing sounded warm and relaxed at even its most accelerated moments.

That combination helps explain why he was later sought out for concert and recording dates by Dizzy Gillespie, Billie Holiday, Thelonious Monk, Gerald Wilson and Wes Montgomery. Land never “made a mistake,” recalls sax giant Sonny Rollins. (He replaced Land in the fabled Max Roach/Clifford Brown Quintet and is interviewed in the 24-page CD booklet that accompanies “Westward Bound.”)

The album is comprised of live recordings broadcast on a Seattle radio station. Land is joined by trumpeter Carmell Jones, bassist Monk Montgomery, pianists Buddy Montgomery, Hampton Hawes and John Houston, and drummers Philly Joe Jones, Jimmy Lovelace and Mel Lee.

Regardless of which configuration of musicians he is playing with here, Land sounds right at home. His playing is authoritative and expertly crafted, yet very much in the moment and imbued with the delight of creation. At times, you can almost feel him smiling through his saxophone.

Jones, who is featured on the final three selections, is best known for the landmark albums he made with Miles Davis in the 1950s. His charged playing on “Westward Bound” pushes the music into high gear with inviting results. The titles of two of Land’s songs here, “Happily Dancing” and “Deep Harmonies Falling,” aptly convey what listeners can expect.

Jen Shyu and Jade Tongue’s “Zero Grasses: Ritual for the Losses” (Pi Recordings)

An award-winning East Timorese-Taiwanese-American vocalist, composer, multi-instrumentalist and dancer, Illinois-born Jen Shyu speaks 10 languages. She sings in three of them on her latest album, the challenging and often stunning “Zero Grasses: Ritual for the Losses.”

As its title suggests, “Zero Grasses” is inspired in part by loss, be it the sudden 2019 death of Shyu’s father or the equally sudden fatal police shooting in 2020 of Breonna Taylor, a 26-year-old Black emergency room technician in Kentucky. Other subjects Shyu examines on this 14-song album range from sexism and systemic racism to her desire to become a mother and grappling with the numbing realities of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Such themes could be heavy going for even the most gifted artists and their listeners. But Shyu and her superb, four-man band, Jade Tongue, have the talent and gravitas to make even the most daunting subject matter worthy of her artistic explorations. Intense and dense one moment, airy and inviting the next, her music can beguile even in its thorniest moments.

The fact that Shyu’s crystal-clear singing and luminous tone at times suggests a modern-day Joni Mitchell at her most daring is a major plus. Ditto the deftness with which Shyu draws from Western and Eastern music traditions, be they jazz and avant-garde, folk song and art song, the new and the ancient (including Indonesian sindhen and Korean p’ansori).

An accomplished pianist and percussionist, she is also adept playing such instruments as the Taiwanese moon lute and the Japanese biwa. But Shuy’s principal instrument is her remarkably strong and flexible voice, which shines throughout “Zero Grasses.”

She is a one-woman, multitracked choir on the heavenly four-part suite, “Living’s a Gift,” which opens the album. On the album-closing “Life As You Envision,” she delivers a haunting ode to cautious optimism in the face of soul-sapping adversity, enhanced by Ambrose Akinmusire‘s finely sculpted trumpet lines.

In between come songs suffused with pain (“Lament for Breonna Taylor,” “Body of Tears”), aspirations born of anger (“When I Have Hope”), stirring testaments to the acceptance of loss (“Father Slipped Into Eternal Dream”) and the embracing of hard-earned truths (“With Eyes Closed You See All”).

In Akinmusire, violist Mat Manieri and drummer Dan Weiss, Shyu has versatile partners who are unusually sensitive to the needs of her meticulously created music. Together, they turn what could be an arduous undertaking into a rewarding emotional and sonic journey that unveils more with each new airing.

Get U-T Arts & Culture on Thursdays

A San Diego insider’s look at what talented artists are bringing to the stage, screen, galleries and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.